Tribes.

Blowing up “ISIS” on Christmas because it’s Christmas is incomprehensible as an expression of Christian morality but coherent as an expression of tribal power. Contra Laura Loomer, vengeful bloodletting is not, in fact, the best way to commemorate the arrival of the prince of peace. But take Jesus and his teachings out of the equation and you’re left with Christmas as a kind of tribal feast day—and scalping a few enemies from the other tribe is, in fact, a good way to celebrate a day like that traditionally.

Trump plainly sees himself as a sort of tribal chieftain for Christians. That’s the only way to reconcile his interest in sectarian violence in Nigeria with his “America First” baseline of not involving the United States in inscrutable foreign conflicts. There’s no national interest in defending African Christians from African Muslims, but there’s an obvious tribal one for him and his core base of post-Christ Christians. And when the interests of the nation and the tribe conflict, the tribe wins out, nationalist pretensions be damned.

Pity the Ukrainians, whose cause lacks the same tribal salience and which therefore reduces America’s chieftain to embarrassing equivocating nonsense like this.

The purest expression of Christianity without Christ came from Trump himself, not coincidentally. At Charlie Kirk’s memorial service, shortly after Kirk’s widow, Erika, moved viewers by publicly forgiving her husband’s killer, the president strode to the mic and said, “That’s where I disagreed with Charlie. I hate my opponents, and I don’t want the best for them. I’m sorry.” That’s the literal antithesis of Christian morality, proof that Trump “does not have any faith” in the words of his friend-turned-enemy Marjorie Taylor Greene.

But there were no mass defections by Christians from the president’s camp after his heresy. Erika Kirk herself remains a loyal Trump ally in good standing. And why not? Hating one’s enemies is squarely in line with the three purposes of post-Christ right-wing Christianity. The first is establishing the right’s cultural hegemony over other American factions; the second is narrowing the parameters of the right-wing tribe to exclude undesirables; and the third is deemphasizing morality as a brake on ruthlessness toward one’s opponents.

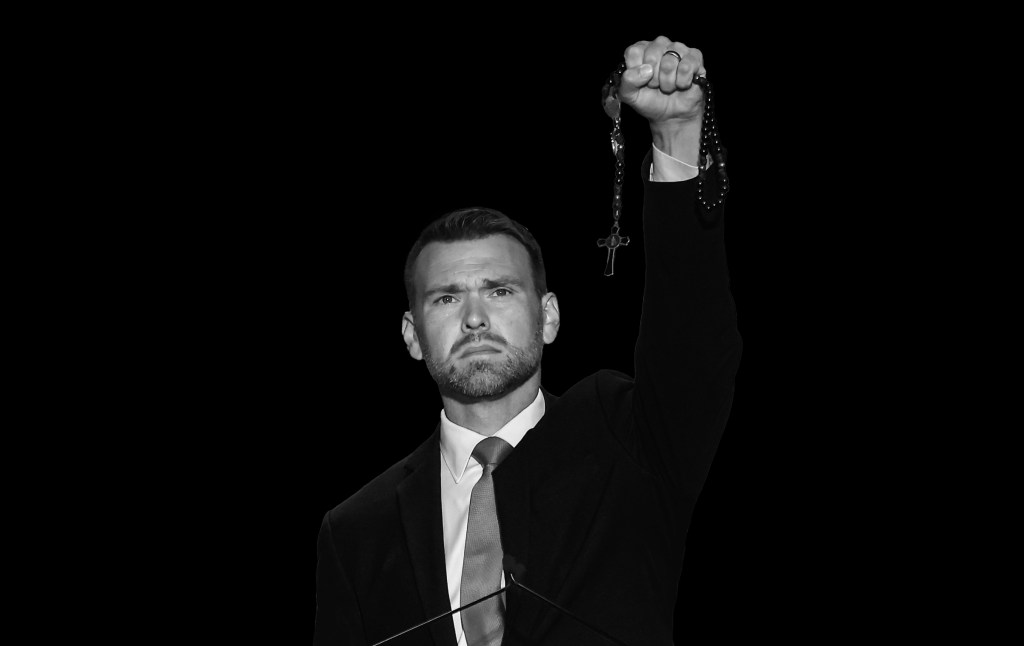

When populist chuds taunt Jews like Ben Shapiro by hooting “Christ is king” or walk onstage at political rallies brandishing their rosaries as if they’re trying to repel Dracula, they’re not expressing earnest Christian witness. They’re signaling that there’s a hierarchy in America and that Christians properly sit atop it.

When Trump’s Labor Department tweets “Let Earth Receive Her King” on Christmas or the Department of Homeland Security declares “we are blessed to share a nation and a Savior,” they’re not just expressing season’s greetings. They’re deliberately flouting the separation of church and state to stress Christianity’s preeminence in the U.S. It’s the same impulse that leads many right-wingers to insist upon saying “Merry Christmas” instead of “Happy Holidays,” which typically has less to do with Christ than with asserting Christians’ tribal authority to define cultural norms in America.

Jesus’ birthday as an occasion to remind the libs who’s in charge: That’s Christianity without Christ.

It would be easier to take their expressions of faith at face value if Trump’s movement prioritized Christian values in any serious way—by stressing moral rectitude, for instance, or championing charity toward the poor. Even something as simple as not overtly gloating over the misery of others, whether it’s illegal immigrants or the Reiner family, would be a small nod toward Christian compassion. But the president’s ethic of ruthlessness makes that impossible. “Our side has been trained by Donald Trump to never apologize and to never admit when you’re wrong,” Greene told the New York Times. “You just keep pummeling your enemies, no matter what. And as a Christian, I don’t believe in doing that.”

Christian identity in the right-wing political space during the Trump era is remarkably short on mercy and brotherhood and despairingly long on vindictiveness and xenophobia. It’s less Erika Kirk showing grace toward her husband’s killer than yokels gathering outside a Hindu temple in Texas to shout about the statue of the “demon god” that the owner erected on the grounds. (“Why are we allowing a false statue of a false Hindu God to be here in Texas? We are a CHRISTIAN nation,” one local Republican put it.) Wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross but with barely hidden contempt for the ideals that both symbols stand for: That’s what Garfield Minus Garfield looks like politically, as predicted.

Hijacker.

It can’t be a coincidence that Christian tribal identity in right-wing America is growing fiercer as religiosity in America declines.

One reductionist theory of Trump’s rise to power is that it’s a reaction by the shrinking white majority to the rise of Barack Obama’s seemingly unstoppable “coalition of the ascendant.” Whites saw blacks and Latinos propel an African American to two easy presidential victories, feared that their grip on the country had finally slipped for good, and rallied to an angry guy who practiced white identity politics. They felt besieged, so they turned to a chieftain who promised not to let the enemy take power without a fight.

Their anxiety about their declining cultural influence led them to prefer a leader who expressed their identity more assertively and tribalistically. In vowing to make America great again, the president was effectively vowing to make it more like it used to be.

Christianity without Christ fits that theory too, though. America has grown less religious and more religiously diverse, causing Christians’ grip on the culture to slip. In Trump they saw a nostalgic nationalist who promised to sustain Christians’ traditional tribal preeminence in the U.S. but who plainly cared nothing for Christian morality. They accepted his offer, and every civic degradation since—flagrant corruption, immoral policies, vicious bullying and extortion as standard government procedure—is a footnote to it.

As with whites, rising anxiety at declining cultural power led Christians to favor a leader who would prosecute their grievances aggressively and combatively. Who needs a softie like Christ when you’re in an existential struggle?

Even so, it’s still hard 10 years later for a nonbeliever like me to understand how Trump managed to co-opt right-wing Christianity.

It’s easy to understand how he co-opted right-wing politics, as that story has been told many times here and elsewhere. The GOP of 2015 was a weak institution—leaderless, out of touch culturally with its own base, captive to a Reaganite “conservatarian” economic philosophy that did little for working-class voters who otherwise preferred right-wing values to the woke left’s. Enter Trump, whose candidacy was based on a single profound insight: Populist conservatives cared a lot more about populism than about conservatism. If you offered them a truckload of the former, he discovered, they’d forgive you for not offering much of the latter.

He hijacked the party with little difficulty because there was no one at the controls. It should have been more challenging for him to co-opt Christianity, or so one would think.

Here, too, he followed the same playbook, promising Christians a truckload of tribal solidarity in hopes that they’d overlook the fact that, as Marjorie Taylor Greene bluntly put it, he “does not have any faith.” It was his only option, really: Because he has few real ideological beliefs and none that override his own self-interest, Trump can offer voters only extreme tribalism. There’s no set-in-stone policy agenda besides immigration to get you excited. All he can promise is that, in the great war of Us and Them, he’s on Team Us and forever will be.

It shouldn’t have worked as well as it did with Christians. Someone is at the controls of Christianity, after all, and he left reasonably clear oral instructions for how his followers should proceed morally. Denominations will differ on certain matters, but all Christian sects agree that you can’t have Christianity without Christ.

Yet that’s not really true for the postliberal Christians in Trump’s movement. For many, their faith has become a political culture more so than a religion. Fully 50 percent of self-described “evangelicals” now say they attend church only monthly or less frequently, a number that’s grown over time.

The answer to how Trump did it must be that American Christianity was also weaker institutionally than it seemed in 2015. Thirty-five years of Republicans courting and consolidating the evangelical vote intertwined political and religious identity on the right, perhaps, to the point where many believers ultimately thought nothing of supporting a president who boasts openly about hating his enemies, about not seeking God’s forgiveness, about going to hell when he dies, and about killing people as a “Christmas present.”

If that’s true then the heavy lifting on breeding a Christianity without Christ was done long before Trump entered politics. By 2015, many right-wing evangelicals were willing to put on red MAGA caps to signal their allegiance to a belligerent reactionary movement; go figure that, by 2015, some people in red MAGA caps would be willing to signal their allegiance to the same movement by waving crosses or rosaries at their enemies.

Many Christians have turned out to like Garfield without Garfield just fine, it seems. There’s a lesson to be drawn there about the tribal appeal of religion relative to its moral appeal, but that’s far too much of a bummer of a topic to explore during the Christmas break.