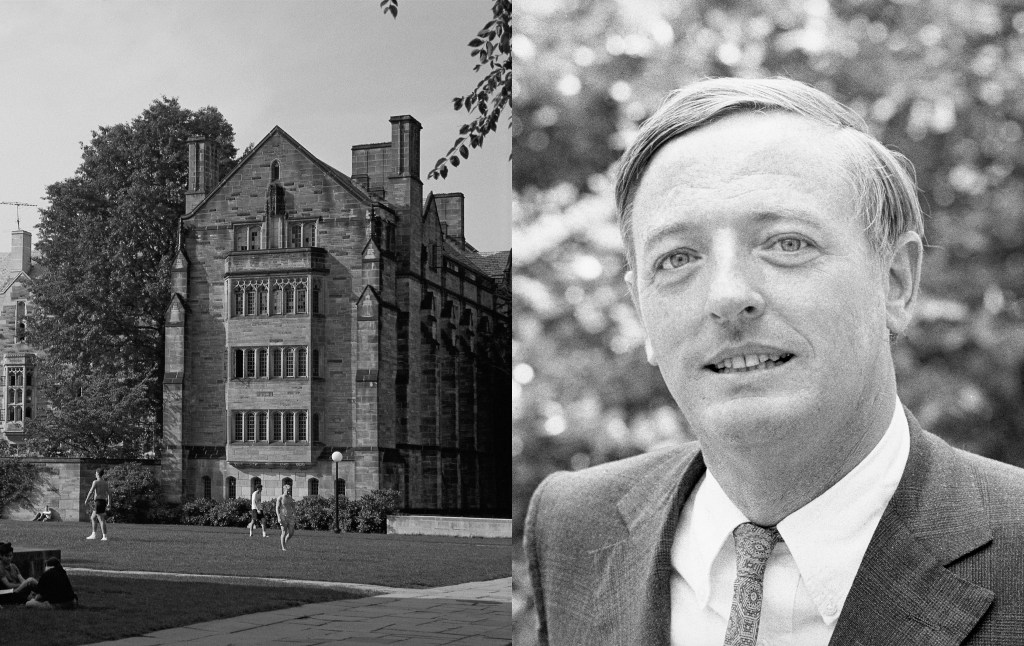

Seventy-five years ago, a dynamic young conservative delivered a blistering assessment of his alma mater, declaring it a hotbed of atheists and socialists. He had a clear purpose: to galvanize trustees and alumni to assert their right to govern the university. The alumni who filled the college’s coffers and the trustees who oversaw the school ought to exercise control over the university, he wrote, up to and including dictating the curriculum and removing renegade teachers who preached the wrong values.

This young Yale graduate was, of course, William F. Buckley Jr. His first book, God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom,” first published in 1951, launched his career. Just four years later, Buckley would found National Review, for a time one of the most influential periodicals in the nation.

Despite methodological flaws, Gamay, as Buckley took to abbreviating the book, remains influential today. It also provides an intellectual blueprint for the recent Republican campaign against higher education.

Buckley’s argument was simple and persuasive. Yale’s money came from its alumni. Its alumni were overwhelmingly Christian and believed in free-market economics. Yet most of Yale’s professors were religious skeptics and big-government partisans. This divergence “produced one of the most extraordinary incongruities of our time: the institution that derives its moral and financial support from Christian individualists and then addresses itself to the task of persuading the sons of these supporters to be atheistic socialists.”

The evidence Buckley presented wouldn’t have stood up in court. When examining the religious leanings of the Yale professoriate, Buckley mostly relies on anecdotal experience, telling readers that several professors he had were either unwilling to profess their Christian beliefs or actively disdained Christianity, treating it as an unscientific superstition. He cites no systematic poll of professors. Instead, he asserts things like, “My opinion is that taking all the courses of the [philosophy] department into consideration, the bias is notably secular, and, in some cases, straightforwardly antagonistic to religion.”

His approach to Yale’s economics program is slightly more robust. He quotes at length from the textbooks assigned in introductory economic courses, whose authors, he argues, “are slavish disciples of the late Lord Keynes”: They want to raise income taxes, establish an inheritance tax, and increase government interference in the economy. Is Buckley cherry-picking his examples? It’s hard to say. The American academic McGeorge Bundy, writing in The Atlantic the year the book came out, argued that he was; Buckley, in his introduction to the 1977 version of Gamay, said he wasn’t. The 2026 reader can only guess who was right.

As for the argument that the trustees and alumni agree with Buckley’s political and religious views, Buckley provides no evidence at all. He just assumes that the bulk of the alumni are believers in God and the free market—a reasonable assumption for Buckley to make in the early 1950s, to be sure, but you’d still like to see some data backing it up.

But the quality of the evidence didn’t really matter. Gamay wasn’t meant to be an exhaustive account. Instead, Buckley was trying to make a point—that Yale, which was established as a religious school, had become almost fully secular. And its economics program had been captured by left-wing, or at least not right-wing, ideas. (Buckley lumped these two ideas together because he believed that “the duel between Christianity and atheism is the most important in the world … [and] the struggle between individualism and collectivism is the same struggle reproduced on another level.”)

He may not have had the goods to really prove his contention, but he was at least directionally right. One only has to look at the campus unrest in the 1960s, let alone in the 21st century, to lend credence to Buckley’s claims.

In addition to documenting the religious and economic attitudes of Yale’s professors, Buckley’s book tackles “the superstitions of ‘academic freedom,’” the basic liberty of professors to research and teach without fear or favor. In its 1915 Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) argued that the principle was essential to maintaining both the truth-seeking and knowledge-passing functions of the university professor.

Buckley didn’t buy it. First, he rejected the idea that academic freedom actually exists. When a faculty committee hires a new professor, it rejects applicants who don’t meet a certain academic standard—for instance, Buckley argued, if an applicant for an English position says he likes Joyce Kilmer’s poetry, the committee has every right to turn him down, since “one cannot be both a scholar and an admirer of Joyce Kilmer.” (Ouch!) Therefore, Buckley asserted, the people most in favor of academic freedom don’t even believe it themselves; if they did, they would just hire anybody with a pulse, or at least a Ph.D.

From there, he argued that while colleges should certainly respect the freedom of professors to perform research freely, they should restrict this freedom in the classroom. He contended that professors should be required to inculcate certain values to their students—principally a belief in Christianity and in the superiority of free-market capitalism—because schools are established to train the next generation to combat evil ideas: “the teaching part of a college is the practice field on which the gladiators of the future are taught to use their weapons, are briefed in the wiles and stratagems of the enemy, and are inspired with the virtue of their cause in anticipation of the day when they will step forward and join in the struggle against error.” For Buckley, the traditional understanding of academic freedom was a strategic blunder.

Buckley’s stance toward academic freedom may surprise those who haven’t read Gamay: They may have assumed that he would be in favor of a broader license for professors, given that the conservative principles for which he argued have so often been suppressed on college campuses in recent years. Until very recently, many colleges required professors to sign diversity, equity, and inclusion statements as a job requirement. These were effectively political loyalty oaths, telling centrists and conservatives that they were not welcome on campus unless they proclaimed, in writing, their allegiance to progressive ideas. Colleges amplified this message when they disinvited prominent conservatives from speaking on campus or investigated professors for saying the wrong thing. Because conservatives (or, at least, those not sufficiently committed to progressivism) were under fire, they were the ones arguing in favor of academic freedom on campus.

In 2026, however, Buckley’s arguments feel more familiar during the second Trump administration. Here’s how the logic goes: The federal government pays colleges a boatload of money for scientific research and student support. But colleges have gone off course—among other things, they’re inculcating anti-American values and discriminating against Jews. Therefore, the government has a duty to revoke funding until colleges change their ways. Hence the high-profile shakedowns of Columbia, Harvard, and other prestigious universities. In a March 2025 letter to Columbia, the Trump administration’s antisemitism task force channeled Buckley: “U.S. taxpayers invest enormously in U.S. colleges and universities … and it is the responsibility of the federal government to ensure that all recipients are responsible stewards of federal funds.” Buckley said much the same thing about Yale’s alumni.

Red-state governments in Texas, Florida, and several other states are even more indebted to Buckley’s legacy. Many of these states have passed laws banning critical race theory and DEI at public universities. Republican governors have also appointed like-minded members to the boards of public universities, trusting that these appointees will root out ideas from the curriculum they don’t like. These actions have had some odd consequences. Most notably, a philosophy professor at Texas A&M University recently had to remove selections from Plato from his course syllabus in order to comply with Texas state laws restricting classroom discussions about race and gender.

Buckley’s logic in Gamay does not translate exactly to all of these examples; Buckley notes in the text that Yale was not taking any government funding. Still, I doubt Buckley would approve of a university—at the behest of the government—forbidding a philosophy professor from teaching Plato. Indeed, this was one reason why Buckley often advocated keeping universities free from government funding: He knew this type of meddling was a distinct possibility. As Buckley’s biographer Sam Tanenhaus said when he was asked what Buckley would think about the Trump administration’s actions toward universities: “I think he’d say, I told you so.”

By now, it’s probably obvious that I disagree with Buckley’s vision for Yale. I think his logic is destined to be abused by unscrupulous actors, and I think academic freedom, as typically understood, matters.

Yet I also recognize that universities did not exactly cover themselves in glory during the past decade. And there is an appropriate time for states and trustees to step in and make changes. Even the AAUP, which today has around 44,000 members, recognized as much. “If this profession should prove itself unwilling … to prevent the freedom which it claims in the name of science from being used as a shelter for inefficiency, for superficiality, or for uncritical and intemperate partisanship,” it wrote in its 1915 declaration, “it is certain that the task will be performed by others.” For years, colleges have indeed been defined by their “uncritical and intemperate partisanship.”

But the way to fix universities is not to establish an alternative orthodoxy, as Buckley argues. It is instead for institutions to double down on academic freedom. That’s why some recent developments, such as colleges establishing new centers for civic thought and university leaders verbally committing to fostering free inquiry and debate, are heartening. Whether these changes will stick is another question. But at the very least they make me hopeful.

After all, as Buckley wrote in his introduction to the 1977 version of Gamay, “from time to time the interests of the state and those of civilization will bifurcate, and unless there is independence, the cause of civilization is neglected.” Let’s hope that university leaders now recognize the wisdom of this statement.