In only three or four lifetimes, the capitalist world went from a situation in which most people lived in conditions that would have been more or less familiar to a serf from the Dark Ages to the one with Bel-Air tailfins and refrigeration and widely available antibiotics, and then, in less than the course of a single lifetime, we went from the age of TV dinners and Pan-Am to the age of the iPhone, AI, and robot taxis. Goodness knows I have my aesthetic bones to pick with all of that: Give me a London taxi driver with “The Knowledge” over some poor lost terrified New York City rideshare driver who doesn’t know where Central Park is because he was stuck in traffic in Luanda or Rawalpindi six days ago—GPS doesn’t give a for-hire driver everything he needs. When I hear people discussing whether they’d go back in time to kill Adolf Hitler before he had a chance to launch his career, I sometimes wonder the same thing about Steve Jobs and the iPhone—not that I’d murder the guy (though many of his subordinates wanted to!), but I might talk him out of it. But, even accounting for these de gustibus trade-offs—or even for the very real and much more significant trade-offs, such as increased anxiety and sexual dysfunction in the generation that grew up in the iPhone world—things are moving, and have been moving, in the right direction, at least in raw material terms. A lot of people get to eat now who didn’t get to eat before, and only the well-fed turn their fat little noses up at that.

But Americans are not used to economic hardship, even of the relatively mild and short-term variety. One of the reasons Donald Trump lost his election in 2020 was the fact that real wages (meaning wages adjusted for inflation) were cratering in the fourth quarter—not only was the average American not better off than he’d been in the second quarter, he was making about $17 a week less in real terms. Real wages continued to plunge under Joe Biden, whose YOLO-spendthrift tendencies, enabled by congressional Democrats and more than a few loose Republicans, and he was, in turn, shown the door. Here is a fun fact: In the third quarter of this year, real weekly wages were, down to the dollar, precisely where they were when Donald Trump got the boot in 2020. Which is to say: So far, the Trump-era recovery has managed only to get wages back to where they were when Americans fired the guy the last time around. (Readers will please mentally insert here all my usual longstanding caveats regarding the superstitious beliefs about presidents and the economy.) The problem, in no small part, is that nominal wage growth (i.e., the number on the paycheck) continues to be undermined by persistently high inflation—inflation that not only has been too high but that has in recent months trended even higher, rising from 2.3 percent in April to 3 percent in September. An inflation rate of 3 percent may not sound like much, but persistent 3 percent inflation over the course of a decade would mean that a worker who had been earning $1,000 a week would be earning the equivalent of $741 a week after 10 years. A worker who got a 3 percent raise every year would be no better off under that scenario than he had been at the beginning—the number on his paycheck would be a little bigger, but inflation would have taken all the real gains.

“In only three or four lifetimes, the capitalist world went from a situation in which most people lived in conditions that would have been more or less familiar to a serf from the Dark Ages to the one with Bel-Air tailfins and refrigeration and widely available antibiotics, and then, in less than the course of a single lifetime, we went from the age of TV dinners and Pan-Am to the age of the iPhone, AI, and robot taxis.”

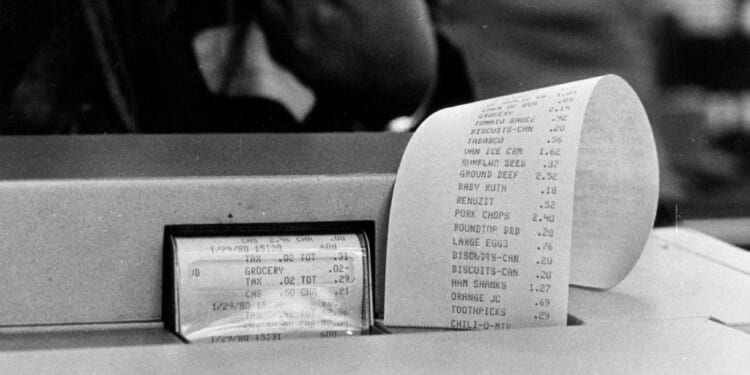

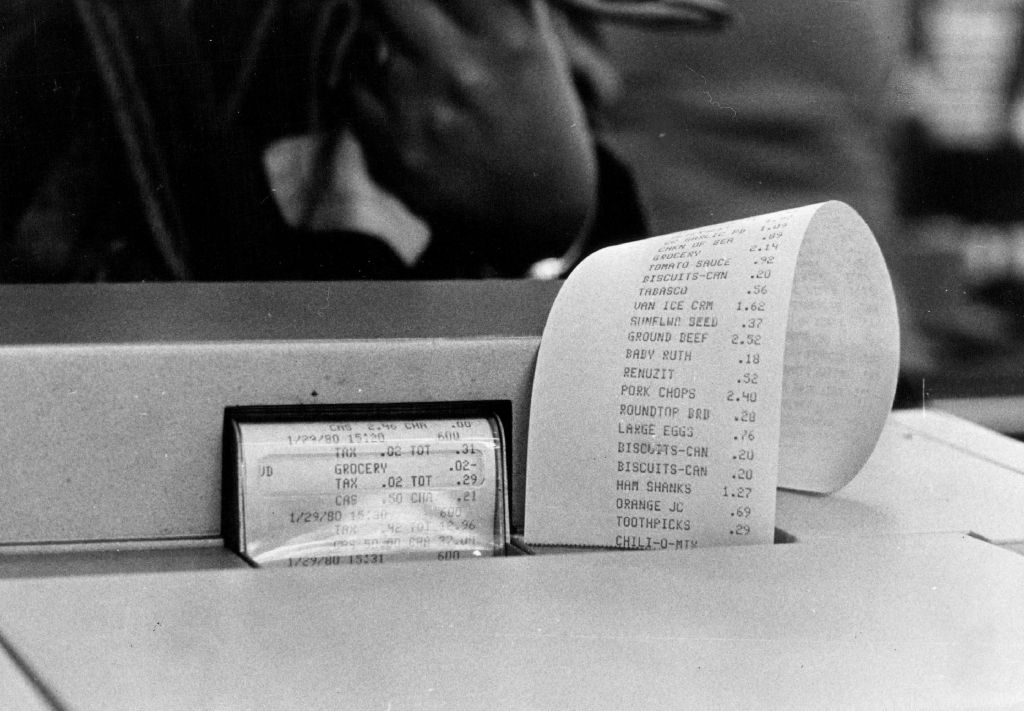

To make things worse, inflation has been persistent in the relatively small things we spend money on every day—e.g., groceries, where inflation is even worse than it is in the overall market—while inflation in the big things—houses, college tuition, health care—has been climbing way faster than wages for a long time, way before the economic dislocations associated with the COVID-19 epidemic and the government overreaction to it. Overall inflation in the Trump era has remained high for a number of reasons, many of them related to the Trump administration’s policy preferences and those of the compliant congressional Republicans who do the administration’s bidding: lots of spending, lots of debt, and what sure as heck looks like a partially successful pressure campaign to keep the Fed from raising interest rates enough to bring inflation down to its target level. But inflation in housing, college tuition, health care, and a few other sensitive and critical goods has been higher for longer as a result of policies that have been even more foolish: artificially constrained supplies (particularly in housing), increases in demand driven both by demographic and economic forces, and a flood of cheap money (years and years of low-interest mortgages, subsidized student loans, and tax-advantaged insurance spending) to make the economic mud Americans are trudging through that much thicker and deeper. This has been particularly depressing for the kind of young people who expect to be upwardly mobile and whose agonies are attached to disproportionate social and political influence: They took on debt to attend colleges they could not afford and graduated into an economy with disappointing real-wage growth and unaffordable housing, with health insurance costs that remain burdensome despite the grievously misnamed Affordable Care Act. If we do not hear very loud complaints from the poor, it is because they are used to feeling poor—but when the middle to upper-middle classes start to feel poor, there is going to be trouble afoot.

Add in a poisonously large dose of historical-economic illiteracy and nostalgia—those “This is what they took from you!” clowns who would break down in nonstop tears if they actually had to endure two weeks at a 1957 standard of living, to say nothing of an 1857 standard of living, and who could not be made to do the kind of work most Americans did in 1920 except possibly at gunpoint—and you end up where we are: at a dangerous political moment.

The good news is that our main economic problems can be mitigated through fairly straightforward policy changes. The bad news is that nobody wants those policy changes to be made, because they would mean reduced government benefits, higher taxes on the middle class as well as on the affluent, less access to subsidized credit for higher education or buying houses, and a period of economic adjustment that probably would be at least as painful as the one Americans went through at the end of the Jimmy Carter years and the beginning of the first Ronald Reagan term, when a relatively responsible governing class acting under the leadership of Fed chairman Paul Volcker (who heroically blew smoke from his Antonio y Cleopatra Grenadiers and the occasional Partagas at the elected rabble throughout congressional testimony) screwed its collective political courage to the sticking place and did the needful thing.

As a matter of pure political calculation, it is worth keeping in mind (should anyone in Washington feel the unaccustomed stirring of political courage) that while Americans in the 1980s sure as heck did not enjoy the process of fixing the inflation problem they really, really enjoyed having fixed it, and President Reagan went from being a basement-dwelling Gallup poll bum in 1982 to winning a 49-state landslide (recount Minnesota!) in 1984, largely on the strength of economic recovery: Real GDP growth topped 7 percent going into the 1984 election season. Average real GDP growth in the Reagan years was more than half-again as much as in the first Trump term or in Obama’s eight years, and more than under Joe Biden, when the economic figures were boosted by the post-COVID recovery.

In much of public life, as in much of private life, the good thing comes after the hard thing. But you cannot get to the good thing without the hard thing. The alternative is to persist in the uncomfortable, frustrating, disappointing mediocrity of the present situation—and how’s that working out for everybody?

Words About Words

I very much enjoyed this New York Times column about one man’s hunt for a piece of costume from a “Planet of the Apes” movie: “I Can’t Stop Thinking About a Primate’s Bathrobe. How Can I Find It?” I would advise the editors over at the New York Times that unless the Geico gecko is more formal in his leisurewear than I expect, all bathrobes are primates’ bathrobes—the primate species include H. sap. That’s right: Your momma is a primate.

A non-facetious question: In what sense is Cheryl Hines a “devoted D.C. conservative”? In what sense is she—Mrs. Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—a conservative of any kind? Her husband is a left-wing lunatic, and the man he works for generally abjures the label “conservative,” one of his few truthful habits, given that Donald Trump is no kind of conservative at all. It would not be entirely unfair to use conservative as contemporary shorthand for Republican-aligned nut, I suppose. But I think the term, and its meaning, are worth fighting for, like the difference between masterly and masterful or forte “FORT” vs. forte “for-TAY.”

And Furthermore …

How long have I been writing about Democratic “moral victories”? Twenty years, maybe? From Slate:

Democrats Just Lost an Election by 9 Points. Why Are They Celebrating?

A moral victory is worth zero votes in the House, but it may well be a sign that the party is in for a good year in 2026.

What in the name of Beto O’Rourke, patron saint of Democratic “moral victories,” are these clowns thinking? A few more moral victories like that and Republicans will rename the moon for Donald Trump.

Elsewhere

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here.

In Closing

I was gratified by the reaction to my Thanksgiving column. In a sense, the first part of this column is a Thanksgiving column, too: It is easy to take for granted—even to be contemptuous toward—the ways in which our lives have improved materially in past decades. I am not much of a neo-medievalist and do not have much use for the heretical (Marcionite!) notion that the material world is cursed and in constant competition with the higher, spiritual things. Material privation can be a tool of spiritual formation, as can other forms of suffering approached the right way, but poverty—poverty unchosen, forcible poverty—leads to spiritual deformation as often or more often. We generally are not better off poorer—not materially, not politically, not spiritually. There are many, many good things to say about the Dominicans and their vow of poverty—but that is a very different kind of poverty than what one sees in rural India or Honduras or, indeed, a few pockets of our own country. American poverty is unusual, globally and historically, because it is largely a non-economic phenomenon, being mainly a manifestation of mental, social, and spiritual dysfunction. (Here I mean real poverty, not relative poverty.) Which is to say, American poverty does not present a path toward spiritual improvement but rather presents evidence of the need for improvement, spiritual and moral poverty being persistent presences even in a country in which there is more than enough to go around.