Upon his death in 1799, George Washington was hailed as “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” It is no wonder, then, that a statue of the “Father of His Country” has stood in front of Independence Hall, our country’s birthplace, since the mid-19th century. It is here, after all, that Washington was unanimously chosen in 1775 as commander-in-chief of the fledgling Continental Army, which he led to an upset victory at Yorktown six years later that “turned the world upside down.” It is here that he was unanimously chosen by his fellow delegates to be the president of the Constitutional Convention. And it is here that, having been the presidential electors’ unanimous choice as the nation’s first chief executive, he served the bulk of his two successful terms, guiding the new government through its crucial early years and setting well-considered constitutional precedents at every turn.

And yet, visit Independence National Historical Park as run by the National Park Service and its allies, and you’ll find that Washington is more heavily criticized now than King George III. He is an irredeemable slaveholder, a hypocrite for the ages, his actions characterized as “deplorable,” “profoundly disturbing,” and as having “mocked the nation’s pretense to be a beacon of liberty.” He stands accused, with other founders, of “injustice” and “immorality.”

Authorized by an act of Congress in 1948 and officially established in 1956, Independence National Historical Park is tasked with “preserving for the benefit of the American people as a national historical park certain historical structures and properties of outstanding and national significance…associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States.” Covering about 50 acres in the middle of historic Philadelphia, the park includes a variety of buildings familiar to lovers of American history, such as Carpenter’s Hall (where the First Continental Congress met), the First and Second National Banks, and replica versions of the Declaration House (where Thomas Jefferson wrote his draft) and City Tavern (where statesmen met throughout the founding period), both of which were (re-)built for the Bicentennial.

The most frequently visited portions of the park are the two square blocks framed by Market Street, Walnut Street, and 5th and 6th Streets. Of these two blocks, the southern one is Independence Square, which features Congress Hall, where the House of Representatives and Senate met for most of their first decade in existence; Old City Hall, where the Supreme Court met over that same span; and Independence Hall itself, where American independence was declared and our Constitution framed. The northern block includes the Liberty Bell Center, where the famous bell hangs, and the President’s House Site, which features the ruins of where Washington and John Adams each lived and worked during most of their presidencies.

The National Park Service’s “interpretations” at these sites leave much to be desired. The President’s House exhibit, at which visitors will read sign after sign suggesting how selfish and unprincipled Washington was, opened in 2010, during the Barack Obama presidency, at the beginning of the woke era. As with many deleterious shifts in our society, however, the change in the park’s tone actually began during George W. Bush’s presidency, if not earlier. The Park Service’s “Long-Range Interpretive Plan,” released in 2007, repeatedly emphasizes “diversity.” It bizarrely characterizes our national motto, E pluribus unum—out of many, one—as meaning that diversity is our strength; inanely juxtaposes Benjamin Franklin’s signing of the Declaration of Independence with “his attempt to control his children’s choices,” and views the world through the lens of “class, religion, ethnic[ity], rac[e], gender,” and “haves” and “have nots.”

At least there are no longer big video screens in the windows of the Declaration House, filled with the much-larger-than-life eyes of the descendants of Monticello slaves, as was the case in the summer of 2024. That display was a product of the National Park Service’s partnership with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation (which maintains Monticello) and artist Sonya Clark, whose works “address race and visibility, explore Blackness, and redress history,” and who said that the eyes were “bearing witness.”

Proclaim Liberty

The Liberty Bell has long been viewed as a preeminent symbol of both American independence and the founding period. Much like the United States itself, the bell came from England but was formed anew on these shores. The original bell arrived in 1752 and cracked on its first test. Americans cast a new bell using mostly those same materials but adding some new materials of their own. What was then called the State House Bell, hanging in what was then called the Pennsylvania State House, rang out to commemorate myriad memorable occasions: It rang for the 1764 repeal of the Sugar Act, to call citizens to debate the Stamp Act the next year, to mark the battles at Lexington and Concord, and in response to the deaths or funerals of Franklin, Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson, Adams, and John Marshall. It rang for the Marquis de Lafayette’s triumphant 1824 return to Philadelphia, for the centennial birthday of Washington in 1832, and for Lafayette’s death two years later. It suffered its final crack, which put it out of commission as a ringing bell, when pealing in honor of Washington’s birthday in 1846. A contemporary newspaper account of that day’s events referred to the bell as “the old herald of Independence in times long past.”

The Liberty Bell seems to have reached a new level of fame the next year, when George Lippard wrote “The Fourth of July, 1776,” known popularly as “Ring, Grandfather, Ring.” Lippard’s fictional account describes a grandfather, waiting in the bell tower, who then receives a signal from his grandson that the Continental Congress has voted to approve the Declaration of Independence:

The old man is young again; his veins are filled with new life. Backward and forward, with sturdy strokes, he swings the Tongue. The bell speaks out! The crowd in the street hear it, and burst forth in one long shout! The city hears it, and starts up from desk and work-bench, as though an earthquake had spoken! Yes, as the old man swung the Iron Tongue, the Bell spoke to all the world. That sound crossed the Atlantic—pierced the dungeons of Europe—the work shops of England—the vassal-fields of France!

Though it appears that the bell didn’t actually ring on that most famous of July 4ths, it hardly matters—one might say that it rang in spirit. It may well have rung on July 8, 1776, when bells across the city chimed in response to the Declaration’s first public reading, which took place in what would become known as Independence Square. While oral tradition holds that the bell did ring in connection with that momentous event, the steeple was in bad shape and apparently under repair, which might have precluded the bell’s use. The steeple housing was replaced following the victory at Yorktown and the bell rehung, after having been hidden in an Allentown church basement during the war. In 1787, the bell rang out for the signing of the Constitution.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was transported by steam train to New Orleans, to Chicago for the World’s Fair, to Atlanta, to Charleston, to Boston as part of a Bunker Hill commemoration, and to St. Louis for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. It took its last trip in 1915, a coast-to-coast journey aboard a steam train to San Francisco—one might call this the original transcontinental Freedom Train—drawing massive crowds and being displayed under a wooden sign reading, “1776 PROCLAIM LIBERTY.” Years later, the bell was lightly tapped so that it could be heard on a radio broadcast commemorating Allied success on D-Day, and in 1961 Gus Grissom wore a picture of it on his sleeve patch aboard Mercury 4, whose space capsule was called Liberty Bell 7.

Yet, in touring the Liberty Bell Center, one would likely conclude that this enduring symbol of American independence has little to do with the American Revolution or the nation’s founding. It is depicted instead mostly as a symbol of the abolitionist movement—as it was abolitionists in the 1830s who first started calling it the Liberty Bell—and of the movements for women’s suffrage and gay rights. It is also depicted as an international, not a uniquely American, symbol of freedom. If anything, it is now presented as a symbol of Americans’ failure to secure liberty. Visitors to the Center will learn that “while the Bell traveled the nation as a symbol of liberty, intermittent race riots, lynchings, and Indian wars presented an alternative picture of freedom denied.” Of the bell’s 1884 visit to New Orleans, the signage speculatively opines, “[P]erhaps African Americans did not share New Orleans’ emotional response to the Liberty Bell.” (Or perhaps, as Americans, they did.) The Liberty Bell exhibit suggests that the founding era didn’t accomplish much except for putting things in motion for real progress to be made in the centuries to come.

The exhibit is also unreliable in other ways. For example, it claims “[t]he Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 strengthened the federal government’s commitment to the survival of slavery.” This could rightly be said of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, or of Dred Scott v. Sandford three years later, in which activist Southern justices declared that the Missouri Compromise had been unconstitutional all along. But it cannot rightly be said of the Compromise of 1850, of which the Fugitive Slave Act was merely a part. That compromise, which allowed California to be admitted as a free state, did not, in all, strengthen the federal government’s commitment to the survival of slavery.

Failing the Chief

It used to be that when one came to Independence Park, one saw where Congress and the Supreme Court had met but was left to wonder about the executive branch. The President’s House was mostly torn down in 1832, with the remaining walls demolished in 1951. In recent decades, archeological digs have unearthed the house’s foundation, but the exhibit subsequently opened on that spot—a joint product of the National Park Service and the city of Philadelphia, and spurred on by activist groups like Generations Unlimited and Avenging the Ancestors Coalition—almost entirely ignores the defining events that took place there during the first two presidencies, narrowly focusing instead on slavery.

“Be aware,” visitors are instructed, “that here you are following in the footsteps of these enslaved as much as those of the Founding Fathers.” Much more so, it would seem. Of the 30 “interpretive” signs on display in the President’s House area, 25 focus on slavery or race relations. One other sign is about the archeological process. Only the four remaining signs focus more broadly on the first two presidents’ actions. Of those four, the largest, on “Executive Decisions,” includes such topics as “Race, Ethnicity, & Country of Origin,” “Closing the Doors Against ‘Dangerous Aliens,’” and “Driving the Indian Nations Out of the Northwest Territory.” (The small print under the last heading notes that Washington and Adams “proclaimed respect for the sovereignty of the Indian[s],” but “could not control white settlers…who frequently violated…treaties.”)

The President’s House exhibit asserts that “[e]nslaved labor played a dominant…role in the nation’s economy” and, indeed, that slaves “built…the nation.” Another sign maintains that the “close proximity” of the President’s House to the Liberty Bell “reminds us that liberty was not originally intended for all.” Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration, however, penned just blocks away, excoriated the “CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain” for his determination “to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold,” lamenting that through “this execrable commerce” these men were being “deprived” of their “liberty” (capitalization in Jefferson’s original). The Continental Congress’s deference to the Carolinas and Georgia—as it finalized what needed to be, as a matter of political necessity, a unanimous Declaration of Independence—marks the principal reason why this language wasn’t included in the final draft. Nevertheless, its existence makes clear that although liberty wasn’t yet realized by all, it was intended for all.

On the whole—quite contrary to the exhibit’s portrayal—the founding generation did more to eradicate slavery than any other American generation apart from the one that shed blood in the Civil War. (At the President’s House a “Slavery Timeline,” spanning three centuries, incredibly doesn’t mention the Civil War—but does find space to highlight Juneteenth.) During the founding era, laws were passed in various states to abolish slavery, partially curb the slave trade, and help facilitate manumission. At the federal level, the founders passed the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, banning slavery in all the territory then owned by the U.S. They passed the Slave Trade Act of 1794, banning the use of American ships in the international slave trade. On January 1, 1808, President Jefferson signed legislation banning all importation of slaves (which—in another concession to the three southernmost states—was the very first day that such action was allowed under the Constitution). Above all else, the Declaration of Independence knocked the intellectual supports out from underneath slavery once and for all. In its wake, slavery’s proponents were eventually reduced to making the politically losing and morally bankrupt argument that that document’s central philosophical claim was a “self-evident lie.”

Little to no mention is made at the President’s House of Washington’s historic actions while living there: appointing an all-star first presidential cabinet and the first six Supreme Court justices; thoughtfully navigating early controversies over how best to construe powers granted under the Constitution, such as during the removal debate, the creation of a national bank, and the president’s Neutrality Proclamation in the war between Great Britain and France; charting a steady course in foreign affairs, thereby keeping America out of European wars; willingly ceding presidential power after two terms, setting a precedent that would last over 140 years. His sage advice to his country (which we would do well to heed today) and his singular heroics in defeating the British before he even entered that house are ignored, too.

The exhibit condemns Washington for bringing slaves to Philadelphia, and then condemns him for rotating them back home (to comply with—the display says “to evade”—a Pennsylvania law saying that they couldn’t stay more than six months at a time without being set free), suggesting that the disruption was too much for them. Ron Chernow writes in Washington: A Life (2010), however, that the slaves brought to Philadelphia enjoyed “a modicum of freedom to roam the city, sample its pleasures, and even patronize the theater,” with Washington buying the tickets. Nothing like this is discussed at the President’s House Site.

Like most of the founding generation, Washington sought the gradual elimination of slavery. In a letter he counted it as “being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by the legislature by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees.” Washington’s hope, felt by many, was that the vile institution, inherited from Great Britain, would gradually fade from the scene without causing too much economic hardship or social disruption for any particular individual.

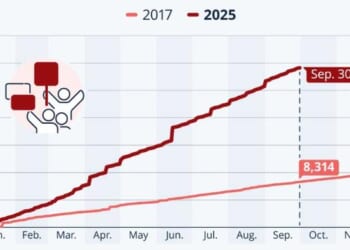

The President’s House exhibit implies that no hope of placing slavery on the course of ultimate extinction was ever realistic, even before the 1793 invention of the cotton gin. A plaque states that “[a]s Washington and Adams governed the new nation, slavery continued to grow”—right above statistics showing that the portion of the U.S. population held in slavery dropped from 17.7% in 1790 to 16.8% in 1800, and that by far the fastest-growing segment of the population over that decade was free black Americans. The exhibit also misrepresents the Constitution’s three-fifths clause, claiming that to “appease slaveholders…Northern delegates…compromised on the issue of congressional representation by allowing each enslaved person to be counted as 3/5 of an individual for population purposes.” The clear inference is that slaves should have been counted fully, which is exactly what the South would have wanted—the better to pad its representation in Congress.

In fact, the cash-strapped Washington was working near the end of his presidency—while in the President’s House—to sell some of his western lands, with the secret intention of using the proceeds to make it more financially feasible to free his slaves. A variety of circumstances kept him from implementing that plan, but Washington had another plan in mind. In his will—which he drafted on 29 handwritten pages in complete secrecy, without the aid of a lawyer or the counsel of his wife, Martha—he declared that his slaves were to be freed upon his wife’s death, or earlier at her choosing. Chernow, certainly no hagiographer, calls Washington’s decision to free his slaves “glorious…. He did what no other founding father dared to do.” Indeed, the country’s leading citizen not only freed his slaves but made provisions for their support and education in his will. Instead of honoring this and his crucial role in the early stages of our republic, the President’s House Site, in the exhibit’s own words, “has been transformed into a space that honors the lives of those enslaved there,” while condemning the man without whom there would be no United States of America.

The Humble Privilege

Across Chestnut Street, in Independence Square, the founders are—thank goodness—portrayed much more favorably. The few park signs succinctly capture the glory of the place. One, on Independence Hall, right behind the Washington statue, says simply, “The Birthplace of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA.” Another, erected in 1908 and affixed to Congress Hall, reads, “In this building sat the first Senate and the first House of Representatives of the United States of America; herein George Washington was inaugurated President March 4, 1793 and closed his official career when herein, also John Adams was inaugurated the second President of the United States March 4, 1797.”

The sparse signage in this section of the park means that those who are visiting Independence Square will have the quality of their experience dictated largely by the given ranger who is assigned to guide them. In all, this is probably a good thing, as it provides some chance of escape from the woke orthodoxy that reigns at the President’s House Site and at so many of America’s present-day museums and monuments.

I took three tours in Independence Square. The tour of Congress Hall was dissatisfying: the tour guide, a middle-aged white woman who had been working there for years and seemed to be respected by the younger rangers, made some false or bizarre claims, including wrongly asserting that the first census counted slaves as only three-fifths of a person. She then asserted that the First Congress, including Madison, looked at the Constitution and realized, “We’ve given ourselves no rights!” Though it’s true that rights aren’t given by man but by God, she meant that only the subsequent passage of the Bill of Rights gave Americans their freedoms. She didn’t quote, and seemed oblivious to, Hamilton’s claim in The Federalist that the unamended version of “the Constitution is itself, in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, a BILL OF RIGHTS.” The ranger did make some good points about the first transfer of presidential power, which took place in that room, and about how Congress dealt with the admissions of new states. Though subpar, her talk was at least more celebratory than condemnatory.

The two other tours I took were of Independence Hall itself. The first, led by a relatively young, ponytailed white man, was good. While not particularly stirring, it was a presentation that one might have expected to hear 20 years ago.

The second tour I took proved more interesting. When we first gathered in the courtroom directly across from the fabled room where the Declaration and Constitution were forged, the ranger fondly mentioned Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin. He celebrated the Magna Carta and the “cherished” freedoms that Americans had inherited from the British, freedoms that he observed had played out in that courtroom. Casting doubt on the notion that the founders’ motivation in declaring independence was chiefly economic, he noted that the word “taxes” appears only once in the Declaration.

After we crossed the hall and entered the famous room, the ranger began by saying that he had “the honor and the humble privilege of welcoming everyone to the birthplace of the United States.” He then asked, “Can you believe” that both the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were debated here in this room? He quoted the former—“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal”—and earnestly asked, “Is that not one of the most inspiring statements in human history?” He characterized the founders’ cause as being “liberty and self-determination.” He highlighted that although most of the pieces of furniture were period-appropriate replicas, the chair at the front of the room was the very one that Washington had sat in as the convention’s president. In his only comment on the topic, he said that through amendments to the Constitution, “slavery would ultimately be resolved.” This presentation, expressing delightful wonder and reverence, was given by an older black gentleman.

Miracle at Philadelphia

In March, President Trump issued an executive order directing the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of the Interior (which oversees the National Park Service) to no longer “inappropriately disparage” our heroes and to start depicting American history more accurately. The Left has responded by claiming that Trump wants, in the words of New York Times culture reporter Robin Pogrebin, “a simplified version of America, a story with kind of less nuance and complexity.” But there is nothing remotely nuanced about the President’s House exhibit, nor much complexity at the Liberty Bell exhibit.

Nor is Independence Park by any means the only place where the Left has hijacked the telling of America’s story. A recent attempt by the National Park Service to establish a woke museum in the basement of the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C. featured coming-soon signs asking questions such as: “Do our heroes change?” “Why a Jefferson Memorial?” “Who Decided to Build the Memorial?” “How Did Americans View This Memorial?” Thankfully, the Trump Administration put an end to this, for now.

When Americans visit Independence Park next year to commemorate the 250th anniversary of their country’s birth, they deserve to see the patriots who successfully established this new nation be celebrated. But unless an overhaul is undertaken in short order, our founders will instead be presented to their countrymen, and to the world, in schizophrenic fashion—generally lauded at Independence Square, oddly ignored at the Liberty Bell Center, and outright condemned at the President’s House.

It is crucial to the country’s future which of two competing interpretations prevails. Is America a nation conceived in liberty or in slavery? Is liberty our nation’s core and slavery the aberration—or is slavery the core and liberty the aberration, with references to “liberty” in our founding documents proof of our hypocrisy? Abraham Lincoln, the founders themselves, and Americans across the generations have maintained the former; those left in charge of our patrimony maintain the latter.

The truth is that the American Founding was a uniquely glorious event and should be presented as such. Our founders constituted perhaps the finest political class in the history of the world, and the Constitutional Convention was a singular gathering of greats. Our nation remains the preeminent historical example, as Hamilton had hoped when writing The Federalist, that good government really can be formed from reflection and choice, rather than from accident and force. As Daniel Webster put it when discussing the creation of our republic in an 1802 Fourth of July speech, “Miracles do not cluster. That which has happened but once in six thousand years cannot be expected to happen often.”