Welcome immigrants. Many, but not too many. Mostly educated and skilled. Always legal.

That is the answer. Or at least a short version of an answer. What’s the question? I’m coming to that.

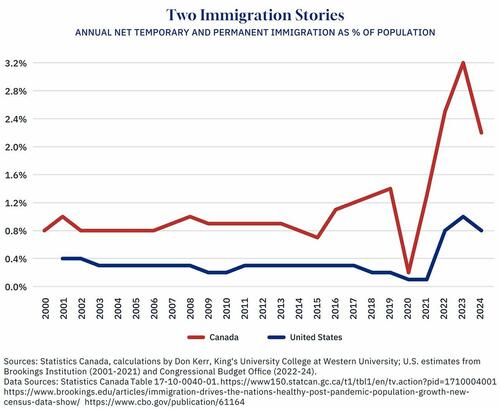

For decades, Canada enjoyed all-party, across-the-spectrum support for immigration. The arrival of new people at consistently higher rates than in Western Europe or the United States did not drive political polarization. This country took in far more immigrants than America relative to the size of its population, and had been doing so for decades, without signs of backlash. Instead of a Left-Right clash on immigration, there was a boring all-party consensus.

When Donald Trump won the U.S. presidency for the first time, visceral anger over immigration was central to his campaign. Perhaps his success with so many voters should not have surprised. By 2016, the share of the American population born outside the country was 13.5 percent, the highest level in more than a century. Maybe a backlash was inevitable.

In Canada, however, it has been well over a century since immigrants were that low a share of the population. In 2016, immigrants were 22 percent of Canadians and rising. That was higher than the U.S. at any time since the Civil War.

Yet in Canada in the mid-2010s, there wasn’t much evidence of a groundswell of popular opposition to immigration, nor were there signs of a political crackup over the issue. Between the Liberal governments of Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin and Stephen Harper’s Conservatives, there hadn’t been much daylight on immigration—not in the shared positive attitude toward legal immigration, nor in their common concern to limit illegal and irregular immigration, nor in the actual numbers of immigrants accepted each year. Governments of different ideological stripes struck roughly the same course for a quarter of a century. The broad strokes of Canadian immigration policy did not whipsaw when the party in power changed.

Immigration sparked conflict in other lands, but something about this nation, or how it did immigration, had delivered a different outcome.

From the start of the century until the early 2020s, the statement “there is too much immigration” was agreed with by only around a third of Canadians, versus two-thirds in disagreement.

A 2018 Pew poll found that 68 percent of Canadians said that immigrants “make our country stronger”—the highest level in the developed world. Just 27 percent said that immigrants “are a burden”—the lowest level in the developed world.

A 2019 Gallup survey found that Canada had the world’s most welcoming and positive attitude toward immigrants. In the U.S., the survey found support for immigration declined with age; in Canada, Gallup found no differences by age group. The most pro-immigration Americans were those in their teens and twenties, but even they were not as pro-immigration as Canadian seniors.

A country that tends to humblebrag about its modest successes had a not-so modest success. The ultimate mark of achievement was that Canadians were not preoccupied with immigration. Public disinterest was a sign of public trust. The subject was usually as newsworthy as functioning plumbing.

Until, that is, everything changed.

The italicized credo that I opened with is the short answer to this question: What is the recipe for a successful immigration system?

Or to flesh it out a bit more: What is the recipe for an immigration system that is likely to deliver long-term and widely shared economic benefits to the receiving country; offers immigrants good odds of success; is genuinely welcoming; is seen as fair and meritocratic; is likely to produce more benefits than costs; builds solidarity and citizenship between native-born and newcomers; and is likely to earn a high level of public acceptance?

Read the rest here…

Loading recommendations…