In the United States, K-12 education is mostly run as a government service. By contrast, higher education is supposed to operate more like a marketplace. In theory, that means competition should drive innovation, keep colleges responsive to students’ needs, and ensure tuition prices reflect the real value of a degree.

But in practice, however, the market for higher education is hugely distorted. A few powerful forces—federal subsidies, confusing pricing, and rigid accreditation rules—distort how colleges and universities respond to students. The result is an education sector that costs more than it should, delivers uneven quality, and innovates too little.

In most markets, businesses succeed only if they deliver what customers want at a price people are willing to pay. If they fail, they lose customers. Consider when Cracker Barrel tried to rebrand itself: Longtime diners pushed back hard, and within weeks, the company reversed course. The message was clear: If customers aren’t happy, the business won’t survive. The same principle would seem to apply to higher education. In a competitive market, colleges would be under pressure to deliver more valuable degree programs at better prices to attract students. Unfortunately, that market mechanism is broken in higher education. Instead of competing to serve students more effectively, colleges are often competing for prestige, rankings, and access to research grant funding.

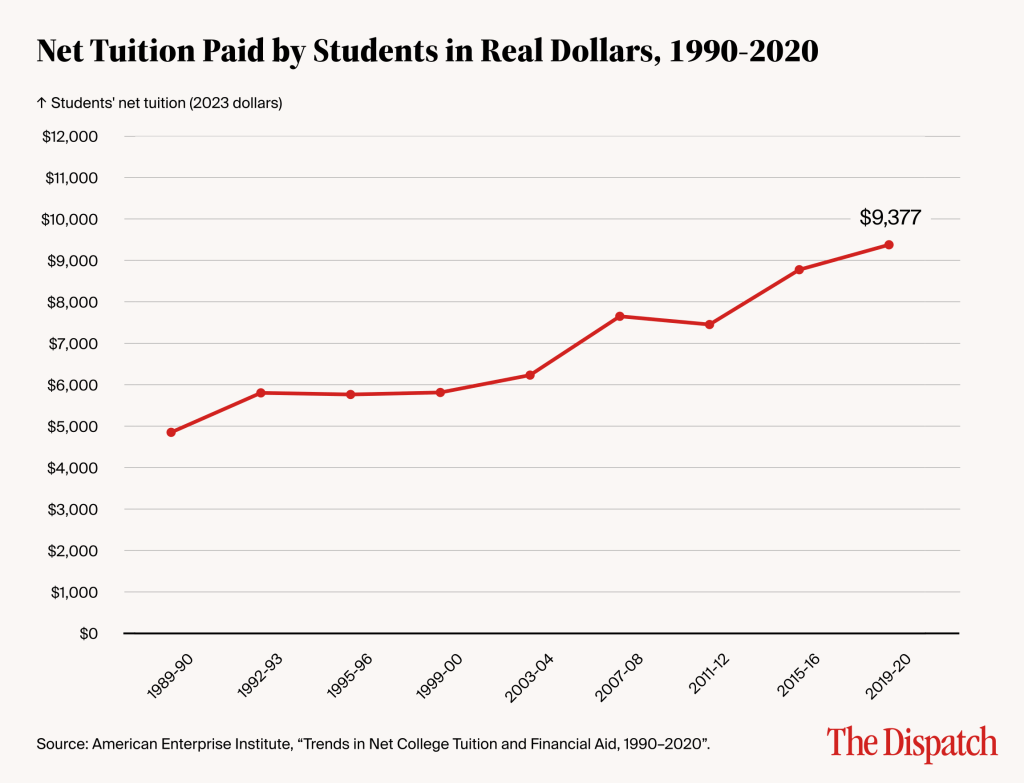

Why is this the case? One major factor is federal subsidies. When the government helps students pay for college through loans and grants, it makes higher education more accessible. But it also changes how schools set prices. Economics 101 tells us that when more money is available for a product, demand rises—and so do prices. Each year, billions of dollars flow to students through Pell Grants, subsidized loans, and work-study programs—all based on financial need—and unsubsidized loans and tax credits. That money is intended to make college more affordable, but it also expands the pool of buyers. Colleges, knowing students can rely on federal aid, face less pressure to keep tuition in check. Over the past several decades, tuition has grown at a rate that far outpaces inflation, and federal subsidies are part of the reason why. Between 1989-90 and 2019-20, the net tuition students pay after financial aid rose $4,526 in real terms (meaning, after accounting for inflation.)

There is also the issue of incentives. When students cover much of their tuition with borrowed or subsidized funds, they may be less sensitive to the quality of the education they’re receiving. Colleges, in turn, face less pressure to deliver value. Over time, this likely means students are paying more but not always getting more value in return. Of course, subsidies also open doors. Without them, many low-income students would have no chance to attend college, which, in the U.S., is an essential tool for social mobility. The challenge is striking a balance: ensuring broad access without fueling tuition inflation or shielding colleges from accountability.

Another barrier to functioning markets in higher education is the way colleges set the cost of enrollment. Imagine if restaurants didn’t list prices on their menus—you would find out the cost only after you ordered, and it would depend on your income or how much the restaurant wanted you there. That is essentially how college pricing works. Schools advertise a “sticker price” that very few students pay. Instead, students receive individualized financial aid packages that vary by family income, academic merit, and the institution’s own priorities. This system makes it nearly impossible for students and families to comparison shop. Applying to college is costly and time-consuming, so most students consider only a handful of schools. The lack of transparency dulls the competitive pressure that, in other markets, would push institutions to minimize costs and maximize value.

To add to the challenge, students often don’t have clear information on college outcomes. Data on graduation rates and subsequent earnings has improved in recent years, thanks to federal reporting efforts and independent research. But much remains murky. That makes it even harder to hold institutions accountable through consumer choice.

Accreditation also further restricts the market. Accrediting organizations decide which schools and programs are eligible for federal aid, and they often lock in the status quo. Students are showing more interest in short-term training—such as tech bootcamps, certificate programs, and employer-based training—and other alternatives to the traditional four-year degree. But many of these options don’t qualify for federal aid because they don’t fit the traditional mold. That means innovative programs, which might better serve today’s students and employers, struggle to get off the ground. Accreditation was designed to protect taxpayers by keeping low-quality providers out of higher education, but in practice it often stifles innovation, keeping new models from having a chance. Further, accreditors have historically failed to weed out the programs of schools that have failed students either through poor employment outcomes after graduation or even instances of colleges unexpectedly closing their doors.

Administrators can generally choose from a small set of accreditors recognized by the Department of Education but the reality is that most employ remarkably similar models. The rules are designed around the traditional degree model, so programs that look different—such as short-term certificates or skills-based pathways—can’t access federal subsidies even when they might deliver better outcomes for students.

Consider a student who wants to complete a one-year credential that leads directly to a good job. Because the program doesn’t fit neatly into the accreditation system, it may be ineligible for federal loans or grants. That student is left with two options: Pay out of pocket, or enroll in a more traditional program that is subsidized but may not be a good fit. Either way, the market is skewed in favor of the traditional four-year degree, even if that isn’t what every student needs.

So what would it look like to bring more market forces back into higher education? Reining in subsidies would be a good start. Federal support should be designed to avoid fueling runaway tuition while still expanding access. One approach would be to tie subsidies more directly to program value, so aid flows to programs that demonstrate strong outcomes for students. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed into law in July makes changes to federal student loan programs by cutting undergraduate and postgraduate programs off from federal loan eligibility if graduates’ earnings fail to exceed what they would have been had they not gone to college in the first place.

Greater transparency is also critical. More transparency on pricing and greater emphasis on outcome data could go a long way. These would allow students to shop around with the same confidence they bring to almost every other purchase in their lives. Accreditation could also be modernized to allow innovative programs to compete for aid while still protecting students from predatory or low-quality providers. Opening the door to affordable and flexible pathways into the workforce would create options that better align with what many students want.

None of these reforms would make higher education a perfectly functioning, competitive marketplace; education is too complex and too important to leave entirely to market forces. But some systemic adjustments could create stronger incentives for colleges to deliver better value and for students to make more informed choices. Higher education will never operate as a completely free marketplace, but making it function more like one—by giving students clear prices, real options, and innovative alternatives—could lead to lower costs and better results.