The temporary suspension of Jimmy Kimmel’s late-night show by ABC after a threat from Federal Communications Commission Chairman Brendan Carr has stoked a firestorm of protest on free speech grounds. Yet although a Trump-appointed, conservative Republican is pulling the trigger, it was actually progressives who gave Carr both of the regulatory weapons he is using in an attempt to censor critics of the Trump administration and its allies: the public interest standard and the news distortion doctrine.

Both of these regulatory weapons are then paired with the concrete (albeit legally dubious) power of the FCC to approve mergers between broadcast media corporations. Nexstar, which owns or partners with more than 200 local television stations, applied last month to merge with Tegna, which has 64 stations. For the $6.2 billion merger to proceed, it needs a special waiver from an FCC-imposed cap on network reach.

This gave repressive weight to Carr’s words in an interview last Wednesday morning. Carr described Kimmel’s comments about Kirk as “some of the sickest conduct possible” and then noted, “We have a rule on the books that interprets the public interest standard that says ‘news distortion’ is something that is prohibited.” Carr then suggested that station affiliates—which are owned by groups like Nexstar and Tegna—should “push back on” the network “because we’re running the possibility of license revocation from the FCC if we continue to run content that ends up being a pattern of news distortion.” However, if pressure from station affiliates on ABC was not enough, then the FCC would try and find some other way to punish the network. As Carr said with mafioso bluster, “We can do this the easy way or the hard way.” Within hours of Carr’s threats, ABC executives had announced their decision to preempt Kimmel’s show.

It is the most direct challenge to the First Amendment in broadcasting yet in the 21st century. But the regulations that Carr is weaponizing were established in the 20th century and have been abused before, albeit not in quite so brazen a fashion.

The public interest standard is the original sin of broadcasting regulation in America. Progressives in both political parties in the early 1920s were unhappy with the unregulated state of the early radio industry, which featured far more radical and minority ownership than would later become the norm in the tightly regulated era of network radio.

So in 1927, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover sabotaged the market-based, emergent order on the airwaves by removing a perfectly functional radio registry. Hoover had manufactured chaos on the airwaves, preventing stations from being able to defend their slice of the spectrum from encroachment. This allowed him to then swoop in and play the hero, promising to clean up the very mess he had created. His solution was the Radio Act of 1927, which stipulated that stations must operate in the “public interest, convenience, or necessity.” That vague standard gave Hoover’s radio regulators significant discretionary power to pick winners and losers in the station licensing process.

However, the supposed “public interest” quickly reduced to the particular and partisan interests of a handful of unelected bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. It also gave the Federal Radio Commission (which became the FCC in 1934) vast potential power over the content of broadcasting, although the agency had to maintain at least a semblance of deference to the First Amendment while wielding that power.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, progressive FRC/FCC commissioners claimed that it was obviously not in the public interest to license stations owned by and operated for communities of immigrants, minorities, or political radicals, including socialists, pacifists, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. This might be discombobulating for modern readers who associate contemporary progressivism with support for immigration and a degree of sympathy for socialism. But early 20th-century progressivism was skeptical of mass immigration, opposed to political radicalism from both left and right, and was generally united by a desire to regulate and rationalize unruly markets.

For example, in 1933, the FRC revoked the licenses of two radio stations in Chicago, both of which primarily served immigrant communities and included non-English programming. The FRC then gave their slice of the spectrum to station WJKS in Gary, Indiana—which was owned by a native-born American—because it promised to feature programs that “stress loyalty to the community and the Nation” and “instruct in citizenship and American ideals and responsibilities,” both of which were goals “well designed to meet the needs of the foreign population” per the commission.

The content-based tampering continued throughout the decade. If stations aired pacifists opposed to the preparations for potential war in Europe, the FCC officially labeled them as propaganda outlets. The FCC instructed stations not to air any advertisements that “defy, ignore, or modify” the New Deal economic micro-management imposed by the National Recovery Administration. They were, after all, simply “using valuable facilities loaned to them temporarily by the government,” and thus had a bounden duty to support rather than undermine the administration and its policies.

These kinds of actions—and they are just the tip of a very large iceberg—should strike the modern reader as intuitively censorial. Imagine if the federal government had claimed the authority to license newspapers and book publishers, and then used that power to justify screening whether the speakers and their speech were sufficiently in the public interest. Yet that is precisely what the FCC did with broadcast speech in the 1930s. However, the government’s ability to police broadcast content waned by the late 1940s because of the rise of the major radio networks, which had the kind of political and economic heft to push back on the government that was not available to independent stations and minority communities in the 1930s.

While some protested this federal power grab at the time, lawsuits accusing the government of censorship were deflected via tenuous legal arguments over broadcast spectrum scarcity, even as a series of Supreme Court decisions bolstered speech protections for print publications. The result was a two-tiered First Amendment system in which protection hinged on whether the speech was in print or on the airwaves. So when Brendan Carr cites the obligation of licensees to operate in the public interest, he is taking full advantage of a progressive carve-out to the First Amendment baked into the origins of our system of broadcast regulation.

The news distortion doctrine is a newer invention. In 1968, congressional Democrats were angry about the negative news coverage they were receiving during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. The American public was riveted to their TV sets watching the massive anti-Vietnam War protests occurring outside the venue, including the crackdown on student activists by baton-wielding police.

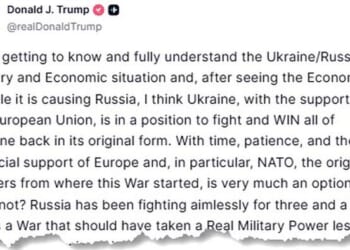

Rather than acknowledging the unpopularity of their pro-war nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Democratic congressmen decided to accuse the reporters of distorting the news. It was a “fake news” style defense more than half a century before Donald Trump co-opted the term. Lawmakers filed complaints with the FCC, like the senator who accused a CBS news crew of dressing up a “girl hippie” with a bloody bandage and prompting her to shout, “Don’t hit me!” at police officers.

While the FCC investigated these accusations and found them baseless, that was beside the point. Notionally, the news distortion rule can be applied in a nonpartisan, content-neutral way to discourage outlets from inventing news events out of whole cloth. But just as often, these investigations are designed to have a chilling effect on critical news coverage regardless of the final outcome. Stations often prefer to remove the targeted speech and avoid the topic in the future rather than deal with the expense and headache of fighting the accusations. Thus, complaints about news distortion are often themselves an attempt to distort the news.

This is also how Carr abuses the news distortion doctrine. The chairman of the FCC has significant, unitary power to launch investigations without requiring a vote of the entire commission. So Carr can publicly accuse a media outlet that airs critical speech about the president of distorting the news, and even open an investigation. This signals the administration’s intent, serves as an implicit warning of potential further regulatory action—particularly the use of the FCC’s merger sign-off authority—and thus places pressure on the targeted organization to slant its coverage of the administration. That includes ABC/Disney’s (temporary) suspension of Jimmy Kimmel’s show, but it might be having an even broader effect. CBS’s trailer for the upcoming season of 60 Minutes included no reference to Trump at all, which raised eyebrows given that CBS recently settled a $16 million lawsuit with Trump under similar pressure from Brendan Carr.

Absent unlikely action from a GOP-controlled Congress, there is little reason for Carr to halt his anti-free speech crusade through the FCC. Indeed, he has already signaled his interest in punishing ABC’s morning talk show The View by abusing another progressive broadcast regulation from the 1960s, the equal time rule. Carr is rooting through the attic of old, flawed media regulations looking for rusty tools that can be weaponized to punish Trump’s critics. It is ironic that progressives created the tools for their own oppression, but the costs of undermining the constitutional order and the First Amendment will eventually be borne by everyone, regardless of their ideology.

Removing Carr’s censorial power, or that of any unprincipled future FCC chairman, would require root and branch reform of the FCC. Elsewhere, I have proposed a series of structural reforms that would better insulate the FCC from partisan pressure, turning it into a more independent agency like the Federal Reserve. It is no accident that the Federal Reserve has (thus far) resisted attempts to replace its officers with toadies and to manipulate its regulations for the administration’s self-interest. In any case, when the 120th Congress swears its oath of office in January 2027 after the midterm elections, it will be the 100th anniversary of the creation of the FCC system, an appropriate time for legislators to imagine alternatives for this antiquated, oft-abused agency.