Every region has its folk-rock anthem, a song for a season and a certain feeling on the wind. If you’ve lived in Alabama, as I once did, you’ve heard Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” blasted at everything from football games to cotillions. Similarly, if you’ve spent time in the Peach State, you’ve swayed and sung and probably shed a tear to Ray Charles’ syrupy yet soulful version of “Georgia on My Mind.” And if you grew up on the Left Coast, the sunny sound of the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” is likely as familiar to you as the peel of a perfect wave.

Regional anthems get murky, however, when one reaches the middle of the country, where I live. A good case can always be made for John Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane”—that little ditty penned by a Hoosier balladeer about two kids growing up in the heartland—or Don McLean’s “American Pie,” an epic story-song about good old boys drinking whiskey and rye, but written by a suburban New Yorker. Travel northward to the upper Midwest and the Great Lakes, where Rust Belt factories give way to dark forests and cornfields yield to deep inland seas and abandoned iron mines, and Mellencamp’s rhymes about backseat debutantes and future football stars can begin to seem a little tame, and McLean’s allegorical references to jesters and crowns begin to sound a bit too arthouse.

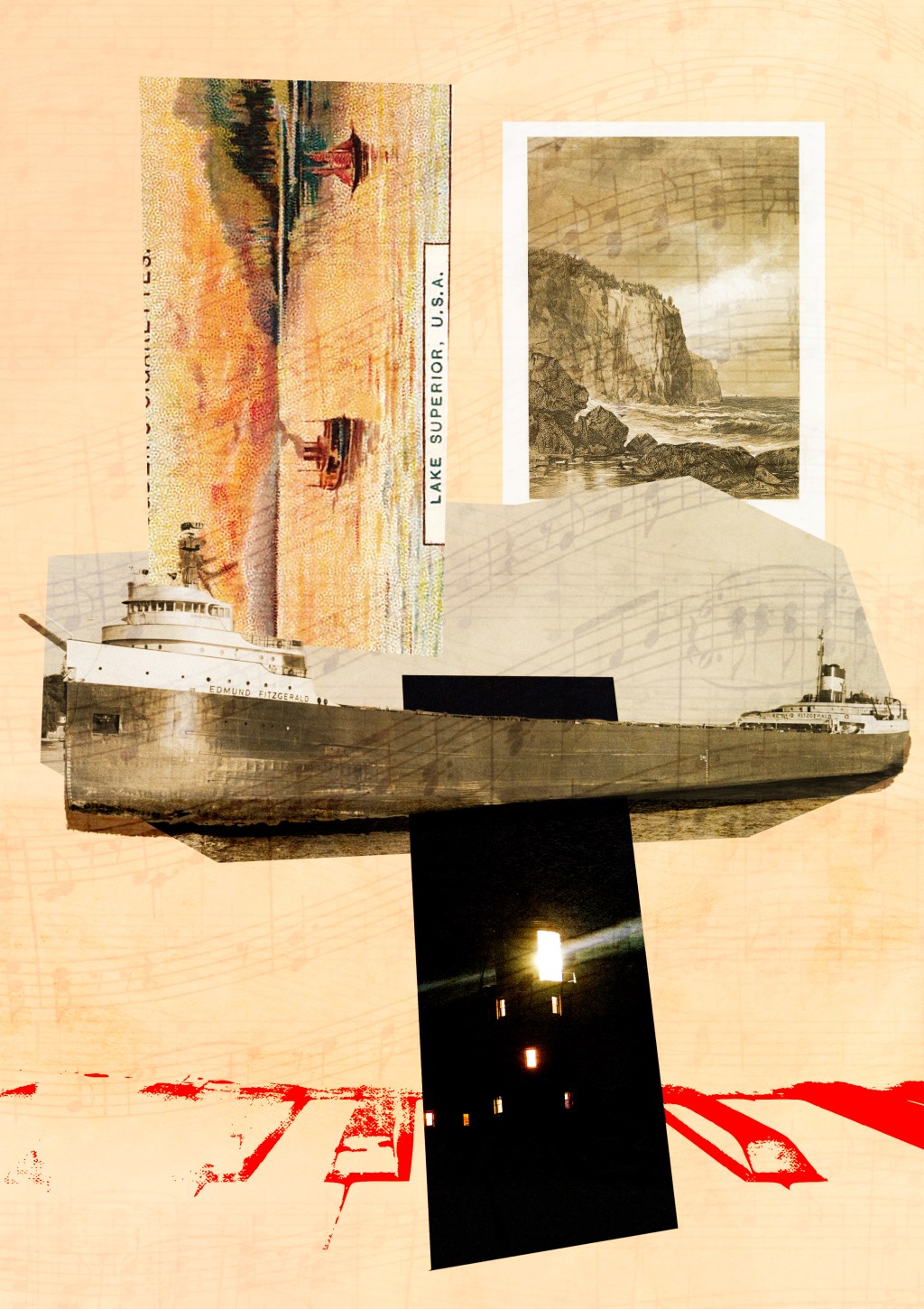

I submit that any serious discussion of flyover country’s definitive anthem must include the “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” by Gordon Lightfoot. Granted, some maintain “The Wreck” isn’t rock ’n’ roll at all, but an old-timey ballad with a soupçon of electric. Add to the debate the fact that the tune was penned and performed by a Canadian and leavened with perhaps the richest irony of all: “Wreck” isn’t an ode to the good vibes of a place, but a mournful dirge about a sunken vessel, sung in an ominous minor chord. It’s an indefatigable downer, a raven among songbirds. It’s a swan song, actually—a black swan—conspicuously out of place among the works of preening, prancing, bleach-blonde raspers like Rod Stewart, whose cloying “Tonight’s the Night,” was the only track to best “The Wreck” for two straight weeks in the November 1976 Billboard Top 100.

Rewatching the cringeworthy if not cancel-ready music video for “Tonight’s the Night,” one can see why Canada (“Wreck” reached No. 1 in Lightfoot’s home country) preferred Lightfoot’s brand of folk-rock ballad to Stewart’s shag-me soliloquies of unsubtle seduction. “Wreck” was performed by a rugged guy sporting a mustache and a full mane of David Hasselhoff hair who looked like he might just be a hunkier version of your local plumber. By contrast, “Tonight’s the Night” was crooned by a British pop star with frosted tips, hair like a fright wig, and a wide leer. The No. 2 song on the American charts that November of America’s bicentennial year was penned as a eulogy to honor the fallen and provide solace to the two nations that share Lake Superior. No. 1, meanwhile, seems to have been written—is there a more delicate way to put this?—with the express intent of getting in someone’s pants, as the music video makes painfully clear.

My father was both a Midwestern farmer and a diehard 1970s music buff, and his influence partly explains my position in the Stewart vs. Lightfoot grudge match. Dad vehemently eschewed what he called “bubble gum pop” in favor of rock ’n’ roll laced with that special strain of darkness Spanish poet Federico García Lorca called “duende,” the black notes that mark the work of artists who conjure their creations from somewhere deep in the gut. Bob Dylan had duende in spades, so Dad printed up the lyrics of “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” and “Maggie’s Farm” and pinned them to my teenage bulletin board.

What I didn’t realize as a kid was that there were many moms and dads like mine in the mid-1970s, the height of the back-to-the-land movement that saw a million or so Americans move out of metros into the hinterlands during a time of high inflation and societal recalibration. The migrators were fed up, and the back-to-the-land movement was their countercultural statement, a move away from urban liberalism to the more grounded centrism of North America’s small towns and rural places. “Wreck’s” comfortable four chords, strummed by a stoic Lightfoot on stage with his trusty 12-string acoustic, seemed as solid as a Chevy two-ton. And his lyrics weren’t a trippy exercise in radical self-indulgence or poetic navel-gazing, but a hallowed versification of a shared tragedy and an homage to a doomed maritime fellowship. My folks were multi-generational farm kids, not back-to-the-landers, but when new country neighbors put “Wreck” on their turntables in ’76, how you arrived in rural America mattered less than that you had come to find common cause in the stanzas of a singalong song of certain doom.

By the time I entered elementary school in the early 1980s, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” had already achieved contemporary classic status, so much so that our music teacher assigned the downbeat tune in the dark days of late October and early November, the gloomy season during which the eponymous vessel, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, sank to the bottom of Lake Superior in 1975 while loaded with iron ore, killing all 29 aboard. It says something essential about Lightfoot’s appeal that a song played for a quarter on the jukebox by farmers and laborers at the rural roadhouse my Uncle Charlie once owned was, at the same time, earnestly sung by an angel choir of elementary schoolers in their autumn recital.

This month, the infamous shipwreck that inspired Lightfoot turns 50 (the song was released around nine months after the November 10, 1975 tragedy), and those 1970s dads are now old enough to collect Social Security. If you sidle up to one at Thanksgiving and sing, under your breath and in your best baritone between bites of turkey, “Superior it’s said, never gives up her dead” he’ll probably slip you a dinner roll and a knowing look.

However, for all its History Channel dad cachet, I would argue that the reputation of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” has suffered disproportionately compared to the hits of Lightfoot contemporaries such as Dylan and Neil Young. Granted, “Wreck” has become a reliable seasonal news peg, sure to earn passing mention in articles commemorating the loss of the ill-fated freighter and its crew. Like the shoulder season from which its springs, Lightfoot’s is a liminal tune, forever doomed to languish in the lost-and-presumed-missing days that fall between Halloween and Christmas. The ides of November are a songwriter’s Bermuda Triangle, a sea of nothingness located between the islands of Monster Mash-styled novelty songs of Halloween on one hand, and the holly jolly of Christmas on the other. For Gen Z, “Wreck” long ago ceased to be the consummate story-song it was for many working-class boomers. If it remembers the song at all, the Snapchat generation has effectively downgraded it to the stuff of novelty themed playlists and music trivia nights.

But the late autumn gut check Lightfoot’s inimitable song offers the more seasoned among us is precisely what makes it so vital to those who insist on its place in the folk-rock pantheon. I argue that Middle America needs a November song that transcends novelty and seasonal good cheer. It’s all well and good to celebrate Arlo Guthrie’s sweetly silly “Alice’s Restaurant” when Spotify cues it up as a Thanksgiving-adjacent feel-good, but November really ought to be a month for grown adults. It’s all fall back rather than spring forward, the season wherein those of us who have lost the ones we love begin to bow and sag like beams under too much weight. It’s the month when armies dig in for the winter. On the Great Lakes, it’s the time when the wicked gales that “Wreck” made famous begin to spin up—storms Michiganders call “The Witch.” It’s a month where tragedy can happen on land and sea, and very often does.

I plan to spend this Thanksgiving in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, about 20 miles west across the bay from Wisconsin’s Door County, so called for its reputation as a “Death’s Door” for hundreds of 19th and 20th-century ships run aground or broken up like so many matchsticks. Sometime after the green bean casserole and stovetop stuffing supply runs dry, I might just make my annual pilgrimage to visit the shipwreck exhibits at Old Mackinac Point, and contemplate what lost souls may still lie under these 300 feet of dark water. November feels right for putting on big-boy pants to honor the dead in their season.

“The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” may seem like an unlikely selection as a definitive folk-rock anthem of its era, but I stand by its nomination all the same. When friends who moved away from flyover country question how a track like this—so melodically straightforward, so simple to sing, so down-in-the-mouth—could earn my pick, I’m tempted to draw on my chops as a scholar of regionalism to explain our Woebegone-styled strain of Midwestern fatalism, our penchant for lost souls and underdogs, our habit of worshipping heroes in what amounts to our own homegrown cult of the dead, our Eeyore-like way of prepping for the worst while working hard for the best. In fact, I think the next time my coastal friends call to debate music with me, I’ll make my point simply by speaking the iconic opening line into the phone—“The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down …” then listen contentedly as they complete the syllogism on their own.