This past Monday, some American states celebrated Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Other states—including Alaska, Hawaii, Maryland, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin—have designated different days to honor Indigenous American peoples and commemorate their histories and cultures. The day also serves to draw attention to the trauma and pain Indigenous people have endured at the hands of colonizing forces.

The disadvantages and discrimination faced by Indigenous peoples in countries subject to colonization were acknowledged in 2007 by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Many countries—including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States—have subsequently ratified it. Inter alia, the Declaration asserts that:

Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. (Article 3);

Indigenous peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced assimilation or destruction of their culture. (Article 8);

Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature (Article 11(1)); and

States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs. (Article 11(2)).

Tensions are emerging when Indigenous claims on natural resources to preserve or enhance their spiritual and cultural manifestations come into conflict with governments’ obligations to manage these resources for the benefit of all citizens. A feature of these resources is that they have historically defied endeavors to assign meaningful legal ownership to individuals or groups. Indeed, to enable efficient use of them, government-guaranteed rights have had to be created to enable investment in, and the derivation of economic benefits from, new technological uses of these resources.

But what if, to satisfy their spiritual or cultural needs, Indigenous peoples require exclusive use of—or indeed claim prior rights of ownership to—these resources? And what if these peoples consider government actions to create the new rights as an unjustified colonizing expropriation of their spiritual, cultural, and economic rights?

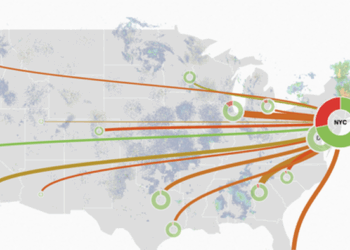

This sort of conflict has emerged in relation to electromagnetic spectrum. Indigenous peoples in the United States, Canada, and New Zealand all hold the view that spiritual beings inhabit and use the airwaves (spectrum) to communicate, and that any other use threatens to disturb these manifestations. In order to mitigate these effects, exclusive control of allocation rights in tribal territories is sought (United States, Canada) or where this is not feasible (New Zealand), allocations of nationwide spectrum and superior rights in the making of spectrum policy governing all users have been granted to Indigenous representatives.

On the one hand, it is argued that if Indigenous people decide to use spectrum in tribal territories to honor their spiritual and cultural practices rather than to enable telecommunications services to be provided with it, then that is a matter for them to decide. This is simply their exercise of self-determination (Article 3 of the UNDRIP).

On the other hand, can it be justified if by exercising their UNDRIP rights—or by government actions prioritizing Indigenous rights over the rights of other citizens—the choices of Indigenous peoples result in wider societal costs? This situation is not merely theoretical. The New Zealand decision to grant 25 percent of commercial 5G spectrum over the whole country to Indigenous interests, who have declared they have no intention of using it for traditional telecommunications services, risks creating an artificial spectrum scarcity for the commercial operators who would otherwise have purchased the spectrum to use for these purposes. The result can only be more expensive telecommunications services for all New Zealanders (including Indigenous peoples, who must purchase their services from the commercial operators).

And although it has been argued that granting spectrum to Indigenous peoples in part redresses the economic disadvantages wrought by uncompensated takings by colonizing forces, this will be achieved only if the spectrum is used for commercial purposes—something requiring significant amounts of additional capital that they may not have access to (or at least, access on equal terms to that available to the commercial operators), and antithetic to any argument that spectrum is required exclusively for spiritual and cultural, and not telecommunications, purposes.

While commemorating Indigenous peoples’ histories and cultures is laudable, honoring UNDRIP may cost societies.

The post Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Spectrum Ownership appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.