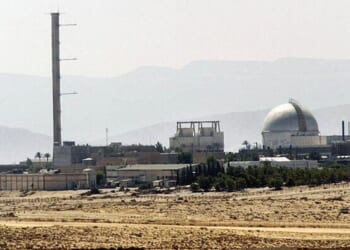

In January 2025, Iran’s currency, the rial, traded at 817,500 per dollar. A year later, the rial trades at a record low of 1.4 million per dollar. Since the 12-day war last June when Israel and the U.S. struck Iranian nuclear facilities, the currency has lost 40 percent of its value. Annual inflation hit 42.2 percent in December. And there isn’t a quick fix.

Speaking at a university last month, Pezeshkian said he saw no obvious solution to the economic crisis. “If someone can do something, by all means go for it,” he said. “I can’t do anything; don’t curse me.” He reportedly told provincial and local leaders to act as though the central government “did not exist” and to “solve your problems yourselves.”

This inflation comes from a combination of cronyism and corruption, general economic mismanagement, and the reinstatement of international sanctions on Iran’s nuclear program. Brandeis University economist Nader Habibi told TMD that the country’s “banking system is completely bankrupt.” He explained that Iranian commercial banks often grant favorable loans to entities associated with the regime, which then struggle to repay them. The central bank bails out the commercial banks, mostly by printing money, fueling further inflation.

The Iranian government has offered some relief, planning to give each Iranian citizen roughly $7 a month in direct payments. But cash handouts, or other similar policies, “are going to result in more inflation, and are just going to postpone the next major economic crisis,” Habibi said.

Michael Rubin, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and an Iran expert, told TMD that the Iranian public is also angered by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) major influence over the economy. The IRGC, which operates independently of the rest of the Iranian military, is estimated to control between 20 and 40 percent of the Iranian GDP, and the government’s latest budget proposal would allocate between 30 and 50 percent of oil revenues to the IRGC.

“If you want to understand the economic impact of the Revolutionary Guard in the Iranian economy, imagine taking the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, merging it with Northrop-Grumman, KBR, and Halliburton, ExxonMobil, and Chevron,” Rubin said.

The fact that demonstrations began with a strike at Tehran’s Grand Bazaar also holds symbolic significance: Both of Iran’s successful modern revolutions, the Constitutional Revolution in 1905 and the Islamic Revolution in 1979, began there. Its merchants also tend to be much more conservative than the educated liberals who form the traditional Iranian opposition, Rubin argued. “These are people who should be in the regime’s camp, very broadly,” he said.

What began as demonstrations against economic issues quickly grew to include underlying anger toward the Islamic Republic—but the anti-government demonstrators have yet to coalesce around a clear alternative to Islamic Republic rule. No political group or individual has yet emerged as a leader of the protests, although chants for Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of the deposed shah, have been heard at many of the protests.

“Let’s not exaggerate” that phenomenon, Alex Vatanka, the director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute, told TMD, arguing that chants for the monarch-in-waiting were an expression of disgust with the current regime more than anything else. “But definitely don’t ignore it.”

In the past, the regime has weathered protests through a combination of patience and lethal force. During the 2022 “women, life, freedom” protests—sparked by state morality police killing an Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, for allegedly not wearing a hijab—Iranian authorities arrested almost 20,000 Iranians and killed an estimated 551.

But the regime may not be so confident that its heavy-handed approach will work this time. On Monday, The Times of London reported on intelligence assessments that Khamenei has developed a backup plan to flee with associates to Moscow if security forces refuse to put down protesters. And they may not. Armed forces, especially the more than 190,000 members of the IRGC, represent both the regime’s most loyal support base and its gravest threat. But “what percentage would actually be willing to kill Iranians, fellow Iranians?” Vatanka asked. Rumors have circulated that the regime has brought in Iraqi and Afghan militias to put down protests, which, if true, would suggest the regime doesn’t trust its own soldiers.

With the protest movement lacking any leader or strategic direction, a mutiny from within the military, especially the IRGC, would seem to be the most plausible path to the regime’s fall. This has happened before—the Pahlavi dynasty took power in 1925 as soldiers serving in a Cossack brigade underneath the old Qajar dynasty seized power. But an IRGC coup would be unlikely to result in a democratic Iran. “Regime change is much more likely going to be a Revolutionary Guard figure declaring himself a military dictator,” Rubin argued.

External, not just internal, factors might be critical in determining the outcome of the protests. “They’re the first major nationwide protests after the state has been exposed as being fundamentally hollow in the aftermath of the 12-day war,” Hussein Banai, a professor of international studies at Indiana University and an Iran specialist, told TMD. During that conflict last year, Israel killed numerous high-ranking Iranian officials, destroyed ballistic missile sites, and neutralized much of the country’s air defenses.

“In the previous demonstrations that we saw, the state had not really been exposed as fundamentally hollow,” said Banai. “There was a real sense of menace.” That isn’t as true today.

There’s also the question of U.S. involvement, which has greater weight following Saturday’s operation in Venezuela. The day before the Venezuela operation, President Donald Trump posted that if the Iranian government “violently kills peaceful protesters, which is their custom, the United States of America will come to their rescue.” On Monday, Sen. Lindsey Graham posted a photo of Trump holding up a signed “Make Iran Great Again” cap.

But analysts don’t believe a major U.S. strike on the Iranian regime is likely. “I always thought the real intent of the message was to try to drum up protest numbers,” Nathanael Swanson, director of the Atlantic Council’s Iran Strategy Project, told TMD. What’s more likely, he argued, is another Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear program.

Speculation is growing among Iranian officials that Israel may use this moment to strike Iran’s nuclear program again—just as Israelis fear that a threatened Iranian regime might initiate another confrontation with Jerusalem to distract from domestic unrest.

A foreign attack could push the regime into collapse—or it could also create a rally-round-the-flag effect, Swanson said. The 1980 war with Iraq solidified the grip of Iran’s theocratic faction on the country, and the regime has consistently leaned on anti-Israel and anti-U.S. rhetoric to drum up support.

For now, the Iranian government finds itself in a dead end, with no end to the economic crisis in sight and protests continuing to spread across the country. But that doesn’t mean that the protesters are on the cusp of victory, Vatanka noted.

“The regime is used to protests that last no more than four weeks,” he said. What happens if the unrest lasts longer? “That’s where things might just take surprising turns, and who knows where we’re going to go.”