You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter exploring the biggest stories in religion and faith. Looking for more ways to support our work? Become a Dispatch member today.

The recent controversy surrounding white nationalist Nick Fuentes, Tucker Carlson, and the Heritage Foundation has sparked several important public conversations, including about the phrase “Christian Zionism” and Christians’ support (or lack thereof) for the state of Israel more broadly. The Dispatch has previously published pieces examining the theological underpinnings of such support, but this week, theologian Brian G. Mattson examines recent claims that “Christian Zionism” is heretical.

Read The Morning Dispatch Free

We’re taking our flagship newsletter out from behind the paywall this week. If you’re looking for a greater understanding of the biggest stories shaping your world, give The Morning Dispatch a try for free—because insights beat outrage.

Brian G. Mattson: Is ‘Christian Zionism’ Really Heretical?

At the recent all-hands staff meeting at the Heritage Foundation held in the aftermath of President Kevin Roberts’ controversial video statement in support of his friend Tucker Carlson, who had hosted a friendly interview on his program with an unapologetic antisemite, an unidentified young female staffer took to the floor during the Q&A and addressed Roberts:

A handful of young colleagues and I had no issue with the points you made in the original video […] Gen Z has an increased unfavorable view of Israel, and it’s not because millions of Americans are antisemitic. It’s because we are Catholic and Orthodox and believe that Christian Zionism is a modern heresy. We believe it does go against church doctrine and the teachings of the early church fathers to use Christianity as a defense for a secular nation. In Christ, there is neither Jew nor Gentile, and there is no salvation outside of Christ. As a young person, many of us are generally tired of foreign entanglements, while our problems in this country worsen.

This undoubtedly sincere statement raises a number of worthy and important questions that are, sadly, wrapped up in an obvious and distracting fallacy. The young woman’s generation has increasing antipathy to Israel, she says, because “Christian Zionism is a modern heresy.” But what has Israel to do with a modern Christian heresy? Has the state of Israel ever embraced or promoted or associated itself with Christian Zionism, other than to accept enthusiastic support wherever it can be found, particularly when in short supply? The modern Jewish state no doubt has its own notions of its origins, essence, and purpose (much of it forged during the blackest years of 1939-1945), and they are unlikely to have been cribbed from modern evangelical Christian sensibilities, making it strange to hold Israel responsible for ideas held by some of its American supporters.

The staffer’s complaint, then, is that if some segment of people support Israel for the wrong reasons, Israel is thereby unworthy of support. This embarrassing non sequitur does not speak well of the generation for whom she claimed to speak. People support right and good things for wrong and bad reasons all the time, and the wrong and bad reasons do not transform the right and good thing suddenly into wrong and bad. Her logic is so transparently poor that less charitable readers might view this public objection to “Christian Zionism” as a red herring to distract from what actually is just antisemitism. Alas, as much as one might wish that this uncharitable reading did not have good support, it is exactly what the likes of Nick Fuentes and Candace Owens and Tucker Carlson are doing when they rail against “Christian Zionists.” The epithet is a cloaking device for conspiratorial hatred of Jews.

But let’s take the young woman at her word: She and her young colleagues do not have an unfavorable view of Israel because of any deep-seated antipathy for Jewish people. Rather (and to admittedly give her the benefit of the doubt because this is not what she actually said), they object to “Christian Zionism” as one rationale for supporting Israel. This is a far more defensible position, in no small part because it happens to be correct. The theological construct she calls “Christian Zionism” is, in fact, an illegitimate rationale for supporting the state of Israel.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Much depends, of course, on what one means by “Christian Zionism.” It cannot possibly mean any and all Christian support for the state of Israel and its right of self-determination, for there are many metrics and motives that cannot be contained under the single, religiously coded umbrella of “Zionism.” The relevant clue is that she purports to be speaking for her “Catholic and Orthodox” colleagues, which purposefully leaves out the no doubt myriad Protestant evangelicals walking the halls of the Heritage Foundation. So the “heresy” she must be referring to, of course, is Dispensationalism: a unique theological framework that has made its home in American evangelicalism for two centuries.

In the grand historical sweep of Christian theology, Dispensationalism is a new arrival. It is a system of reading and interpreting the Bible developed by early 19th-century British Plymouth Brethren teacher J.N. Darby. It divides the history of salvation as recorded in the Bible into distinct periods or “dispensations,” the most important of which is that between Israel and the Christian Church. These represent two distinct “ages” or “programs” in God’s redemptive history. Dispensationalism looks at the two testaments, “Old” and “New” as the nomenclature goes, as practically alien to one another. The Old Testament is a Jewish book for Jewish people with Jewish promises, but the New Testament is a book mostly for Gentiles. God has two separate “tracks” for the salvation of humanity. While the church does include both Jews and Gentiles, the national promises to Israel continue unabated in perpetuity. This is why Sen. Ted Cruz, in his recent combative interview with Tucker Carlson, explicitly justified his support for Israel by quoting a portion of the Abrahamic promise directly from Genesis.. The key proposition for Darby is that God’s original promises to the nation of Israel—land, covenant, blessedness, vindication, salvation—remain essentially unaltered by the advent of Jesus, the Christ (i.e., the “Anointed One” or “Messiah”). The New Testament church represents something of a “side quest,” to put it in terms Gen Zers would understand. Dispensationalism, which provides the underlying rationale for evangelical “Christian Zionism,” believes that the nation-state of Israel still has a significant, perhaps even primary, role to play in God’s overarching plan of salvation—what theologians call “redemptive history.”

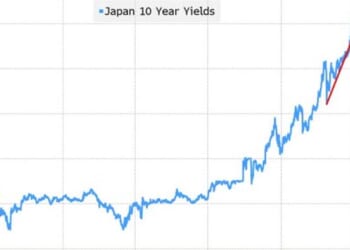

Perhaps Britain ultimately proved too suspicious of innovation for Darby, but his ideas found massive success by emigrating to welcoming North America. In 1909, C.I. Scofield published his famous Scofield Reference Bible, which incorporated Darby’s ideas wholesale, particularly his view of eschatology or the “End Times.” In order to make Dispensationalism’s idiosyncratic understanding of the New Testament vision of the future coherent, Israel as a nation—land and Temple—has to play a critical role. The problem in Darby’s day was that there was no state of Israel and there was no Temple. Younger people can only imagine the excitement that accompanied the news that the state of Israel, after nearly 1,900 years, would be reconstituted in 1948. Evangelicals were treated to book after book not only explaining its redemptive-historical significance, but also using the event to predict the timing of the second coming of Jesus Christ himself. This is the milieu in which Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins much later published their blockbuster series, Left Behind, which is a fictional narration of the Dispensational view of the end times.

Is it a “modern heresy”? If one defines heresy as a decisive departure from the ecumenical creeds of Christianity, probably not. Dispensationalists can and often do affirm basic Christian commitments about Christ’s coming, the resurrection of the dead, and life everlasting. Nevertheless, the Heritage staffer is correct: Dispensationalism is profoundly out of step with apostolic teaching and the early church witness. She should not have just spoken on behalf of her “Catholic and Orthodox” colleagues; Protestants—Lutheran and Reformed (such as myself)—belong there, too. This is as “catholic” or universal a conviction as one may hope to find.

Dispensationalism is essentially unhappy with the settlement of the very first theological debate in the history of the post-apostolic Christian church. In the second century, a teacher by the name of Marcion rejected the Hebrew Bible, or the “Old Testament.” In his view it is a Jewish book written for earthly (not “spiritual” or “heavenly”) Jewish people, and he went so far as to suggest that the “god” of those Scriptures was a violent, tribal, even evil “demiurge” who was to be superseded by the newly revealed gracious and loving “God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The universal orthodox Christian response to this actual heresy, from the pens of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Tertullian, was emphatic and would prove deeply enduring: The Hebrew Bible is Christian Scripture. Not just occasionally or incidentally, as if its Christian content is a few scattered Messianic prophecies. Rather, it is Christian Scripture in toto.

No doubt this offends the sensibilities of Jewish and Dispensational readers alike, but it is the bedrock belief of Christian theology from the beginning. The apostles and post-apostolic fathers taught this without reserve or hesitation, and they did so for very good reason. The Gospel of Luke records that in one of Christ’s post-resurrection appearances, he said, “This is what I told you while I was still with you: Everything must be fulfilled that is written about me in the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Psalms” (Luke 24:44). This is a shorthand description of the entire Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh: torah (law), navi’im (prophets), and ketuvim (writings). Luke then writes that Jesus “opened their minds so they could understand the Scriptures.”

And their subsequent understanding of the Scriptures is just what one finds in the texts of the New Testament. Paul’s custom was to go into synagogues and to “reason with them from the Scriptures, explaining and proving that the Christ had to suffer and rise from the dead” (Acts 17:2-3). The epistles of Paul, James, Peter, Jude, John, and especially the Epistle to the Hebrews bristle with quotations from Hebrew Scripture (in Greek translation, from the Septuagint). In 1 Corinthians 15:3 Paul recites for his readers a formulation he received from the primitive church in Jerusalem, making it the earliest recorded Christian creed: “For what I received I also passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures.” For the apostles and the early church, the Hebrew Bible is fundamentally and intrinsically Christian Scripture, divine revelation that authorizes their doctrines.

Perhaps an all-too-brief summary is in order: Jesus claimed, and his disciples and the religious leaders of the day understood him to have claimed, to be the very embodiment and fulfillment of Israel’s sacred offices. He is the “greater Prophet” Moses foretold (Deuteronomy. 18:15-19; John 12:48-49). He is the Priest “in the order of Melchizedek” (Psalm 110:4) who offers himself as an atoning sacrifice that rends in two the veil covering the Holy of holies in the Temple (Luke 23:45; Hebrews 10:19-22). He is the promised King, descendant of David who has been enthroned at the right hand of God (Psalm 110:1; Acts 2:34-36). Moreover, Jesus claimed to be the fulfillment of Israel’s institutions. He is “lord of the Sabbath” (Matthew 12:8) and the true Temple—the place where God and human beings meet (John 2:19); he was to be called “Immanuel” which means, “God with us” (Matthew 1:23).

Someone who keenly understood these claims is the late Rabbi Jacob Neusner, in his acclaimed book, A Rabbi Talks With Jesus. He imagines himself as one of the young Jewish men following Jesus around as it is recorded in the Gospel of Matthew. Again and again, he understands this rabbi from Nazareth to be saying that he is the Torah, that he defines the Sabbath, and that he is the Temple. Neusner could not ultimately bring himself to accept these radical teachings, but there is no doubt that he understood these were the claims Jesus was making.

Nondispensationalist Christian theology understands the offices and institutions of Israel to have been “types” or foreshadowings of future, greater realities—after all, it is the Hebrew Scriptures themselves that point forward to a greater prophet, priest, and king. These offices and institutions are like architectural models that, once the building is completed, have completed or fulfilled their purpose and function. The land Abraham was promised foreshadowed the eventual new heavens and new earth, a “New Jerusalem” (Hebrews 11:10). The same is true of Sabbath and Temple. In his published 2019 Gifford Lectures, N.T. Wright describes the metaphorically “cosmic” transformation Christ was bringing:

What Jesus did in the Temple and on the Sabbath, and how he explained those actions—these events were earth-shattering. But the earth they shattered was the first-century Jewish earth. And the purpose of this shattering was not to destroy but to fulfill. (N.T. Wright, History and Eschatology, 177)

That last word is important. Christianity does maintain that national Israel’s covenant purposes and function have been put out of gear, retired, made obsolete in terms of redemptive-historical significance, but this is not what is often derided as “replacement” theology. Properly understood, it is fulfillment theology. Wright, again: “[T]o distinguish between a signpost and the building to which it points is not to say anything derogatory about the signpost” (175). Much less is it to say anything derogatory about Jewish people. That anyone would abuse these doctrines in service of antisemitism is an affront to the Christian gospel, which, Christians believe, is for Jews and Gentiles alike.

There is an insurmountable gulf, a stubborn impasse between Christianity and Judaism. The debate between Christians and Jews has been ongoing for 2,000 years and will certainly continue long into the future. But there is an extraordinary benefit to historic Christian understanding when it comes to modern-day questions surrounding the state of Israel. If a Christian comes to understand and believe that the state of Israel no longer has redemptive-historical significance, the question is then disentangled from needless and distorting religious baggage and put squarely back into its proper domain. Nobody asks the religious rationale for why we should be allies with Canada. That is a matter of international relations, not biblical exegesis. What is its form of government? Do its citizens enjoy civil liberties and the rule of law? Do they share our moral values? Believe in human dignity? Is there freedom of speech, religion, press, and association? These are the relevant considerations—and the Jewish people and their state would be only too happy to be judged by them instead of the double standards to which they’ve become sadly accustomed. Like the Heritage staffer, I am a Christian, a theologian even, and I agree that Christian Zionism in the form of Dispensational theology is a terrible reason to support Israel. Unlike her and her Gen Z compatriots, I can spot a non sequitur and therefore I can also see the many good reasons to support Israel.

John Fea: How Slavery Divided American Churches

Nearly 20 years ago, historian Mark Noll published a book arguing that the American Civil War was as much a theological crisis as it was a civic one. As part of our Next 250 essay series, historian John Fea took a detailed look at how the issue of slavery drove a wedge between American Christians, and how the theological debate over slavery changed as the war progressed.

Early in the war, Northern clergy railed relentlessly against the sin of secession and defended the idea that the purpose of the war was to keep the Christian Union intact. In 1861, Barnes told his listeners that the Civil War was not “a war for liberating by force the four millions of men which are held in bondage in the South.” Barnes believed that slavery was an “evil,” but the emancipation of the slaves was “not the object of the war,” nor should it in “any way become the object of the War to secure this result by force of arms.”

After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the ministerial response to the war began to change. Most historians agree that Lincoln’s decision to issue this decree gave the North a moral cause for which to fight that was more urgent than the preservation of the Union. After 1863, more clergy began to conceive the conflict as a war against slavery.

It would be wrong to give the impression that Northern clergymen only became interested in the emancipation of Southern slaves after 1863. The early-19th-century abolitionist movement had its roots in the Second Great Awakening. William Lloyd Garrison, one of the most radical of the abolitionists, believed that the United States could not truly call itself a Christian nation unless slavery was abolished. He proposed that the North secede from the Union to remain free from the sinful stain of slavery. Revivalist Charles Finney concurred with Garrison about the need for separation: “To adopt the maxim, ‘Our Union even with perpetual slavery,’ is an abomination so execrable as not to be named by a just mind without indignation.” Similarly, about a week before the attack on Fort Sumter in 1861, New England clergyman Zachery Eddy told his congregation to separate from the South so that the North could “develop all those forces of a high, Christian civilization.”

Another Sunday Read

- Earlier this year, Dispatch Faith featured an essay from Father Gregory Jensen, an Orthodox priest, on the surge in men converting to Orthodox Christianity. In the New York Times this week, Ruth Graham did some deep reporting on what the upswing in converts looks like in parishes across the country. “But a homegrown Orthodox Christianity is strikingly emergent,” she wrote. “Many of the young Americans new to the pews have been introduced to Orthodoxy by hard-edge influencers on YouTube and other social media platforms. Critics call the enthusiastic young converts ‘Orthobros.’ One night this summer, the young adults of All Saints Orthodox Church in Raleigh, N.C., gathered at a bookshop and bar on the city’s north side. At the event’s peak, there were a mere handful of women present, and more than 40 men. The men noticed, and believed they knew why. Orthodoxy ‘appeals to the masculine soul,’ said Josh Elkins, a student at North Carolina State University who was chatting with other young men. ‘The Orthodox Church is the only church that really coaches men hard, and says, This is what you need to do,’ said Mr. Elkins, 20, who casually quoted a second-century martyr and rattled off terms like ‘monarchical episcopate’ in conversation.”

Religion in an Image