Here at The Dispatch, we’re dedicated to cultivating the next generation of thinkers and leaders—that’s why we’re proud to provide low-cost, high-quality Dispatch memberships to students looking to stay informed, think critically, and better engage with the world around them

With your help, we can offer these students free Dispatch memberships and ensure they’re engaging with content that promotes the core values that make our country great—individual liberty, pluralism, patriotism, and capitalism.

Your support can help provide a new wave of young conservatives with better journalism, more thoughtful dialogue, and—hopefully—a brighter outlook on our future.

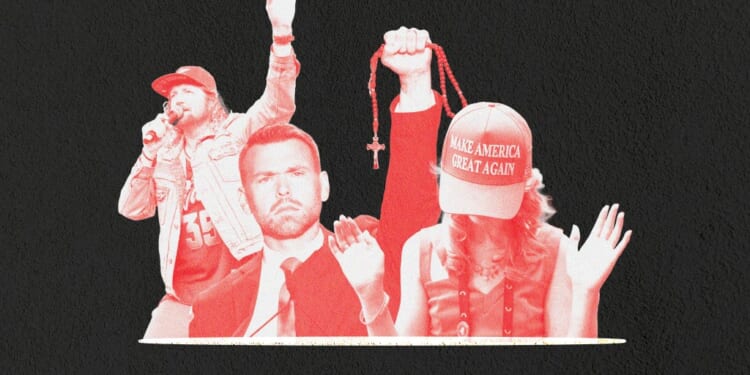

Welcome back to Dispatch Faith. A few weeks ago in this newsletter, I tried to put into words my angst and bewilderment in attempting to assess the fractures among Christians in the U.S. Today, Contributing Writer Paul Miller puts a sharper point on some of the same questions I’ve wrestled with: What is MAGA Christianity, and is it Christian?

He does so by examining some of the fruit of the movement—crystallized in a sense during Charlie Kirk’s memorial service—but also places it in a centuries-long story, tying this new schism to the Magisterial and Radical reformations.

Paul D. Miller: Is MAGA Christianity True Christianity?

“Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven.” These words, from Matthew 7:21, are among the more frightening words that Jesus spoke

It was clear to many observers that Charlie Kirk’s funeral last month put on display two versions of Christianity: the first, rooted in the gospel, in forgiveness and love; the second, rooted in justice, vengeance, and anger. Erika Kirk’s gospel versus Donald Trump’s, in a nutshell—but also Marco Rubio’s against Tucker Carlson’s, or Rob McCoy’s against Jack Posobiec’s. The contrast was shot throughout the service.

How stark is the contrast? Is MAGA Christianity–the kind exemplified by Posobiec’s call to arms, or Trump’s comment that he hates his enemies–so different as to be a false religion? Are MAGA Christians who cheer on such comments akin to those who say, “‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’” to whom Jesus will reply, “I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness” (Matthew 7:22-23)?

Even to ask the question is provocative and could anger some readers. How dare I presume to judge someone’s eternal salvation by their political choices? How dare I make party affiliation a matter of primary importance? How dare I confuse the political application of the gospel with the gospel itself?

The thing is, conservative Christians make those kinds of judgments all the time—every time they call left-wing churches false churches. And they’re not necessarily wrong to do so. In fact, all Christians make such judgments whenever we decide with whom we would share fellowship, which churches to go to, what creeds to profess.

In fact, Jesus commands us to carefully discern who is, and who is not, truly among his followers. How dare I not scrutinize closely those who publicly use the name of Jesus while lying, calling evil good, and perpetrating injustice? All Christians are called to exercise discernment, to seek wisdom, to beware false teachers. When MAGA Christianity so clearly and so publicly parades its religion, when it waves a Jesus flag in our faces, it invites—demands, even—a response from other Christians.

Judging others.

Politically conservative American Christians regularly make judgments about who is, and who is not, a true Christian. For example, Charlie Kirk repeatedly and publicly claimed that you cannot be a Christian and vote for a Democrat. By doing so, he conceded that some political choices (abortion, in his view) are ethical choices of the first rank and that one cannot affirm the gospel while contradicting its clear and direct political implications.

To be clear, I think Kirk was right: Some political choices are intrinsically anti-Christian. I hope every church in America would publicly condemn, say, fascism as definitionally opposed to true Christianity. I hope they would excommunicate any unrepentant fascist from their membership. I use the fascist example to demonstrate the principle that, yes, we can and should judge some political choices as being anti-Christian. Put another way, we can and should judge some of those who say “Lord, Lord,” to be insincere because of the fruit of their actions, including their political actions.

If theological conservatives grant that we cannot take everyone who says “Lord, Lord,” at face value, we should apply the same caution and scrutiny to those who invoke Jesus’ name from all political camps. So, politically conservative American Christians today need to be extremely careful about the company they keep. But I fear too many automatically trust anyone who waves a Jesus flag or invokes biblical rhetoric.

Rainbow Christianity.

How do we judge? We might start by using the yardstick that conservative Christians use to condemn left-wing Christians. They look at two things: theology and practice.

A century ago, mainline churches closely allied with the American ruling establishment began drifting leftward. These churches jettisoned their theological seriousness in service of left-wing social and political activism. The respectable elite in the mainline churches accommodated to “modernism,” and deemphasized supernaturalism, sin, and judgment to protect their intellectual credibility with an increasingly secular elite. They threw out their historical theological commitments and prioritized the social and political agenda of the establishment.

That split—the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the early 20th century—is still with us today. The modernist churches drifted into the watered-down, anemic mainline churches of today, hollowed out and dwindling in number. J. Gresham Machen famously denounced their drift in his 1923 work, Christianity and Liberalism, accusing liberal theology of becoming a wholly different religion. Liberal theology denied supernaturalism and biblical authority, looked to Jesus as a moral example but not an atoning sacrifice, and turned salvation into social improvement and the church into a club. It was the club of the American ruling class.

Machen would be unsurprised to see the liberal mainline of today deny the traditional teachings of Christianity on sexual ethics, for example by proudly flying the rainbow flag out front of their historic buildings, which offends the sensibility of conservative Christians today. The “Rainbow Churches” are the latest example of exchanging biblical teaching for social respectability. In some ways, these churches can look and sound almost identical to conservative churches. They both recite the Apostle’s Creed and could probably answer each other’s catechisms. But conservatives look deeper and find a different gospel, and thus a different religion. Conservatives judge liberal churches to be a false religion because liberal theology denies basic tenets of the gospel (like Jesus’ atoning sacrifice) and liberal practice denies longstanding Christian ethical teaching.

And the mainline drift leftward seemed to leave theologically conservative Christians nowhere to go but rightward. We saw the dynamic play out over the course of the 20th century: The rise of MAGA Christianity on the right is, in part, a reaction to the rise of Rainbow Christianity on the left.

Magisterial vs. radical reformations.

It is more than that, of course, and that story does not excuse MAGA Christianity’s own problems and excesses. So what about MAGA Christianity’s own theology and its own practice? It’s tempting to answer with a short synopsis of views held by white evangelicals today, drawn from public opinion polling, to paint a picture of MAGA theology. But I want to start further back and tell a story of where MAGA Christianity comes from in hopes of showing what authentic gospel impulses may lie within that we can affirm, even as we try to root out any error.

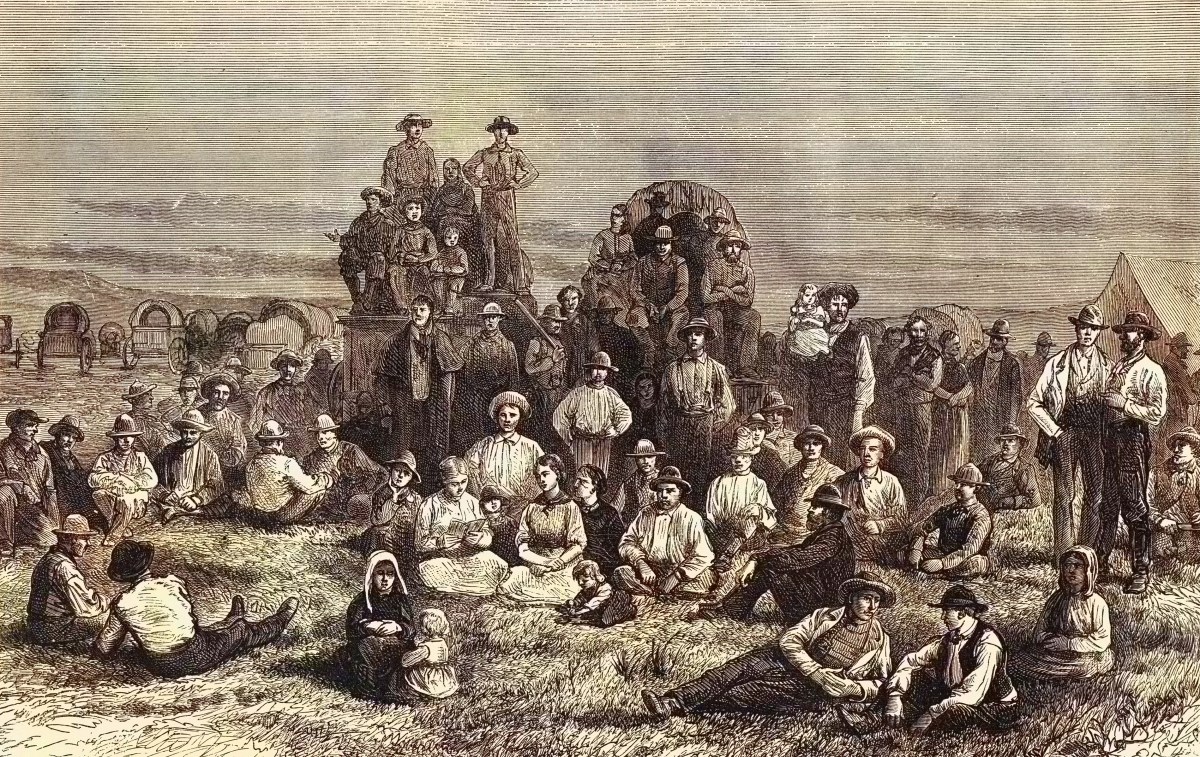

Where does MAGA Christianity come from? The landscape of American Christianity today lies downstream of the Reformation-era split between the Magisterial Reformation (high church) and the Radical Reformation (low church). The Magisterial Reformation was elite, top-down, intellectual, and close to state power; the Radical Reformation was populist, bottom-up, emotional, and disempowered.

The Magisterial Reformation was the Reformation of Martin Luther and John Calvin. It led to the institutions and denominations we still have today: the Lutheran, Presbyterian, Anglican (and later Episcopal) churches, the Reformed theological tradition, and more. It became the quasi-established religion of the United States. Until the 1960s, upper-crust, East Coast Protestantism was the reigning orthodoxy in America. Nearly half of American presidents have been either Episcopalian or Presbyterian.

The Radical Reformation was the Reformation of the Anabaptists and Mennonites; later, the Quakers, Puritans, and Baptists. Their Reformation took them further afield, theologically and politically. They were anti-establishment and lacked the power to build as many lasting institutions, but had an enduring populist power. The spirit of the Radical Reformation resurged in the Second Great Awakening and became the religion of the American frontier in the 19th century and the fundamentalist movement in the 20th. It also flared up with the Azusa Street Revival and the birth of Pentecostalism and the charismatic movements.

More recently, it gave birth to the Christian Right and the Moral Majority in the 1970s and 1980s. Baptist, charismatic, and nondenominational churches—most of red-state America—are heirs to the Radical Reformation. MAGA Christianity is merely the latest example: You hear the Radical Reformation every time a MAGA figure rails against “elites” and “the establishment.” The Radical Reformation and its offshoots are, by definition, cut off from tradition, determined to go it alone and reinvent everything from scratch. That makes it dynamic, energetic, volatile, and prone to bursts of both creativity and avoidable mistakes.

Mutual embrace or mutual enmity?

MAGA theology and practice are anti-establishment, low church, bottom-up, and populist. That doesn’t by itself make MAGA Christianity either good or bad. Both the Radical and Magisterial Reformations were important and authentic embodiments of the gospel. I’m not telling a story in which one side is easily identified as the good guy. Rather, both sides emphasized different aspects of the gospel, but they tended to go awry when divorced from each other.

The Radical spirit without a Magisterial anchoring could become anarchic, as in the German Peasant’s War (1524). It could become wholly concerned with inner spirituality to the exclusion of social concerns, as in the Pietist and Anabaptist traditions. It could become anti-intellectual, as with 20th century American fundamentalism. It could turn legitimate political causes, like anti-communism, into religious crusades that tolerated no dissent. And it could devolve into political tribalism, as with today’s MAGA Christianity.

But the Magisterial tradition without a Radical emphasis on personal zeal and biblical fidelity could become theologically rootless and devolve into a political weathervane. While the Radical spirit rightly led some American evangelicals to abolitionism when that stance was risky and unpopular, most elite, mainline churches made their peace with slavery because they feared abolitionism was destabilizing and extreme. They prioritized respectability and social order over the revolutionary and liberationist implications of the gospel.

In the early 20th century, the Radicals stubbornly, and rightly, clung to their Bibles and their belief in miracles, becoming fundamentalists, while the respectable elite churches accommodated to “modernism” and became the liberal mainline. The mainline substituted the Social Gospel for theology and gave itself over to whichever cause was fashionable with the elite of the day.

Neither the Magisterial nor the Radical does well without the other. Neither the Radicals nor the Magisterium are necessarily heretics—but a heretical impulse lies within each. But a key difference today is that, for possibly the first time in history, the Radical version has become the establishment. I’m not aware of another instance, in 500 years of Protestantism, when the spirit of the Radical Reformation had so clearly become the political establishment of a great power. (Perhaps the parliamentary victory in the English Civil War, but I leave it to a better historian than I to say. I also note that victory was short-lived and immediately supplanted by a revival of the Anglican establishment.)

It is hard to overstate how unusual it is that Charlie Kirk’s memorial service was both an evangelical-charismatic worship service and simultaneously a state funeral with speeches by the president, vice president, secretaries of state and defense, and the director of national intelligence. As Peggy Noonan observed, the memorial service was “the biggest Christian evangelical event” in the United States since 1979, and “the GOP is becoming a more explicitly Christian party than it ever has been.” The Radicals may feel no need of Magisterial roots or anchoring, because they have become their own anchor. If so, the heretical impulse has no check.

Charlie Kirk’s memorial.

Charlie Kirk’s memorial included some beautiful and moving tributes to Kirk anchored in a genuine Christian message of love and forgiveness. And it also featured the dark, anarchic spirit of unmoored, unhinged Radicals. Indeed, some were not recognizably Christian: It was angry, vengeful, deceitful, and manipulative. Shortly after Erika Kirk expressed forgiveness in Jesus’ name, President Donald Trump, who claims to be a Christian, took the stage and said, “I hate my opponent. And I don’t want the best for them.” It was a stark reminder of who MAGA Christians have bound themselves to in the Republican Party.

But Trump was only the final act. He was preceded by other speakers who called for vengeance, coupled with a manipulative use of Christian rhetoric. Jack Posobiec, a conspiracy-mongering agitator with a record of fabrication, lies, and ties to white nationalists, came onstage holding aloft a rosary and a crucifix.

Posobiec seems to care about Christianity chiefly because it is the religion of Western Civilization, his true passion. Nonetheless, Posobiec compared Charlie Kirk to Moses and Jesus. Just as Moses brought his people to the promised land, “Charlie Kirk brought us to the promised land.” Just as Jesus died for your sins, “Charlie Kirk died for all of you.” Jesus rose from the dead, and “Charlie Kirk’s gift of his sacrifice means that Charlie Kirk will live forever.” Posobiec promised that, when we look back on how Western Civilization was saved, we will see that it “was saved through Charlie’s sacrifice in the only way possible: by returning the people to Almighty God.”

As he concluded, Posobiec started shouting, drawing from Ephesians 6: “Are you ready to fight back? Are you ready to put on the full armor of God and face the evil in high places and the spiritual warfare before us? Then put on the full armor of God. Do it now, now is the time. This is the place. This is the turning point, for Charlie.”

But the Apostle Paul in Ephesians was exhorting his readers to be spiritually ready to resist sin and the devil—not whipping up a crowd to exact vengeance for a political murder.

“We are on the side of God!” yelled White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller, who, to my knowledge, does not claim to be a Christian. “We will defeat the forces of darkness and evil!” Consciously or unconsciously, Miller was echoing John 1 (“The light will defeat the dark”) and Philippians 4 (“We stand for what is good, what is virtuous, what is noble”) while heaping derision on unnamed enemies. “You have nothing. You are nothing. You are wickedness. You are jealousy. You are envy. You are hatred.”

In the Old Testament, Joshua—leader of Israel after Moses’ death—encountered an angel of the Lord. “Are you for us, or for our adversaries?” he asked. “No,” the angel replied (Joshua 5:13-14). He simply refused to dignify Joshua’s question; God is not a puppet or a mascot to place on one side or another in a merely human dispute. Instead, the angel commanded Joshua to remove his sandals and show reverence to God’s holiness.

MAGA Christianity unmoored.

If MAGA Christianity is the latest iteration of the Radical Reformation, it is one shorn of all ties to any Magisterial anchor. It has completely cut itself loose from all moorings in traditional Christianity and is in danger of becoming as wholly alien to the gospel as the liberal, mainline churches.

MAGA Christianity is populist, anti-elitist, bottom-up, and fueled by emotion more than ideas. It is driven by charismatic movements like the New Apostolic Reformation, not the old, established denominations. (Southern Baptists may vote for Trump, but, for the most part, they are not manning the barricades and rarely go to his rallies). They use Christian language, cite Bible verses, and sing along with Christian hymns. If you only look on the surface, it can be hard to tell the difference between MAGA religion and historic Christianity. But while MAGA Christianity looks and talks a lot like historic Christianity, it departs from it in important ways.

That makes it all the more important to carefully sift and weigh the movement, to discern if it is truly Christian. MAGA Christianity is a political-religious movement with extraordinary power and appeal—yet it is also a movement with a strong and rising chorus of critics from both within and outside professing Christianity. Though some do, not all critics argue in bad faith, from anti-religious bigotry, or from the progressive left. Some are coming from sincere love for fellow believers, and “faithful are the wounds of a friend,” (Proverbs 27:6).

If we are to judge them by their fruits, then it is fair game to observe that MAGA Christianity is a movement that shouts, “We are on the side of God!” while joking about hating your enemies. It is a movement that couples the Lord’s prayer with images of American military prowess. It is a movement that storms the U.S. Capitol and violently beats up scores of police officers so that they can pause to pray in Jesus’ name in the chamber of the U.S. Senate. It is a movement that invokes biblical language about spiritual warfare to whip up partisan frenzy.

If you want a longer, more scholarly discussion, I have already written at great length about it. As a political scientist, I fear MAGA Christianity is a movement that holds extraordinary danger for the American republic. But more importantly, as a Christian, I fear that if you are in this movement and feel no discomfort whatsoever, it is a movement that holds extraordinary danger for your immortal soul. To many of those who say, “Lord, Lord,” Jesus replies: “I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness.”

Hal Boyd: When the Latter-day Saints Came Marching

Deseret Magazine Executive Editor Hal Boyd wrote this week’s TheNext250 essay for us, reflecting on the recent shooting of a Latter-day Saint church, persecution Joseph Smith and the LDS church faced two centuries ago, and lessons the country can learn from them today.

After the Grand Blanc shooting, David Butler, a member of the church, was moved by his faith to start a fundraiser to support the widow and son of the perpetrator. To date, the fundraiser has raised more than $380,000 in less than two weeks. Many of the donations are relatively modest contributions of $10, $25, or $50.

Some donors wrote notes, such as this one, from Chris: “I’m so sorry for what your family is going through. It’s so hard to have to deal with consequences of the choices our loved ones make. I hope the money helps, but mostly I hope you can feel the compassion we have for you.

David French, writing for the New York Times, applauded the effort and quoted writer Kelsey Piper who said on social media that if America is to survive, it will be because people forgive when “they should never have had to.”

To that sentiment French adds the following: “America has witnessed two remarkable acts of forgiveness in the last month. Erika Kirk forgave the man who killed her husband. Latter-day Saints loved the family of the man who massacred their brothers and sisters. A nation that produces such acts of such love is a nation that still has life. It’s a nation that still has hope.”

More Sunday Reads

- For Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Deborah Danan writes about the commingled grief and joy of Jews in Israel mourning the second anniversary of October 7, which occurred during the weeklong joyous holiday of Sukkot. “The convergence of the festival’s religiously required joy with the memory of mass death set off a broader debate over whether celebration and grief could coexist. Some religious leaders and community groups, including the Reform movement, urged weaving remembrance into holiday rituals — lighting candles, reading names, adding prayers for the fallen — while others argued that Sukkot’s happiness should remain intact, with official mourning deferred. Some Israelis traveled south to visit sites of the attacks, including at official memorials at some of the kibbutzes that were devastated on Oct. 7, but larger crowds were expected on Wednesday, the first of the intermediary days of Sukkot. Travel is prohibited on the first day for those who adhere to traditional interpretations of Jewish law. Even among the bereaved, observance varied. British-Israeli Gaby Young Shalev, whose younger brother Nathanel Young, a soldier, was killed in action on Oct. 7, said her family chose to celebrate the festival with friends and relatives before turning to commemoration. ‘I tried not to think about the fact that it’s Oct. 7. Because I really think it’s important that we don’t let these atrocities of Oct. 7 ruin our chagim,’ she said, using the Hebrew word for Jewish festivals.”

- For Arc, Brad East has a fantastic profile of Leah Libresco Sargeant, an atheist-turned-Catholic intellectual who graces our pages fairly frequently these days. “It was shortly before moving to California that Sargeant became Roman Catholic. Viewed from one angle—and certainly her readers and friends saw it this way—the shift from rationalist atheist to baptized believer was extreme. What hath Athens to do with Jerusalem? Or for that matter San Francisco with Rome? For the new convert, though, it made all the sense in the world. Think of it as a two-step shift. The first step was toward theism, not Catholicism. What changed her mind was morality. She became convinced that, if good exists, then God must too. She approached ethics just as she did mathematics, because deep down Sargeant is a quant. … Looking back in Arriving at Amen, she describes her conversion in almost purely mental terms, as if she were the famed brain in a vat pondering the being of deity. ‘Math is written into the world around us,’ she writes. She resolved to approach the objective existence of morality and its Maker ‘via proofs by contradiction,’ a practice of mathematicians sussing out errors in their theorems. As she turned inward to see the flaws in her premises, she surprised herself with an epiphany. ‘Morality,’ she writes in Arriving at Amen, ‘wasn’t just a rulebook but some kind of agent.’… In short, although she resisted the conclusion (or was it a solution?) with all her strength, she finally welcomed its inevitability. ‘I had just enough love in me to be able to be warmly surprised to find out the rules I loved, loved me back.’”

Religion in an Image