You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter exploring the biggest stories in religion and faith. Looking for more ways to support our work? Become a Dispatch member today.

Especially in light of her more recent popularity thanks to film and television adaptations of her work, novelist Jane Austen will always be associated with love and romance literature of a pre-Victorian England. But Dispatch Contributing Writer Karen Swallow Prior argues in this week’s essay that, as we mark Austen’s 250th birthday this week, we really should remember her as being one of the most significant virtue ethicists of the last three centuries.

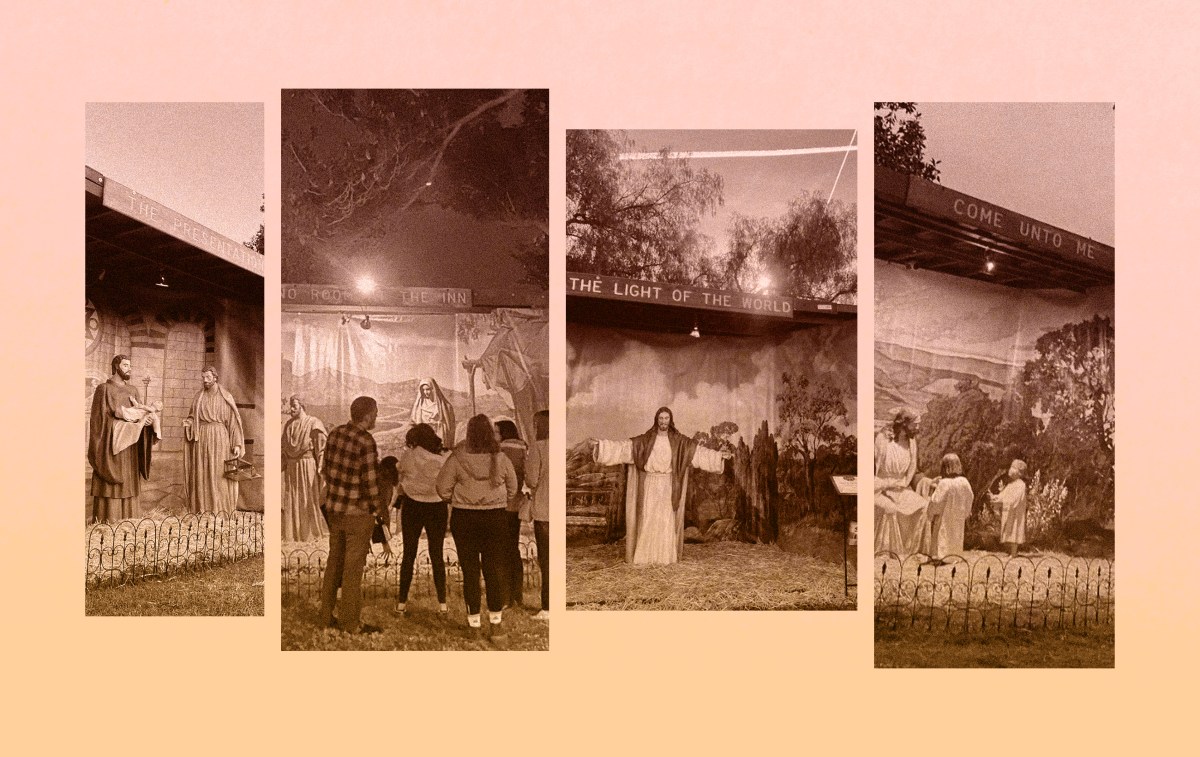

I also want to be sure to highlight for you a story I’m excerpting in today’s newsletter but that you can find in full on our website. California-based writer Mark Kendall reports on a tableau of Nativity scenes displayed on a public street for nearly 70 years in his suburban Los Angeles hometown, attempts to scrap them through the years, and what they might teach Americans about religion and the public square today.

Tired of chaos and toxicity? Get some good news instead

The negativity of today’s 24/7 news cycle is crushing. At The Progress Network, we decided to create something more balanced. Our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right?, combines intelligent analysis with underreported stories of progress from around the world. It’s positive news you’ve never seen before: never fluffy, but always uplifting. Readers of The Dispatch can sign up for free!

Karen Swallow Prior: Jane Austen’s Novels Aren’t Just Romantic

Tuesday marks the 250th birthday of Jane Austen, and all year, this sestercentennial anniversary has been celebrated worldwide with tours, festivals, film screenings, teas, lectures, and balls across the U.K., North America, Australia, and beyond. But the best way to celebrate Austen is simply to read (or reread) her works. They have, perhaps, more to show us today than ever.

In After Virtue, the late philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre describes Austen as “the last great representative of the classical tradition of the virtues.” Austen wrote comedy, MacIntyre explains, “for the same reason Dante did.” As Christians, both Dante and Austen recognized “the telos of human life implicit in its everyday form.” Austen—a devout Anglican and daughter of a faithful Anglican priest—is thus an essentially Christian and classical ethicist. Austen’s novels are ultimately about what virtue—good character—looks like in everyday life and how everyday life can serve to develop character.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

The novels reflect Austen’s real life and her genuine faith. Much about these is preserved in the historical record through family correspondence and other writings. Among the texts preserved are three prayers Austen wrote, prayers rich in theological understanding and in the language of the Book of Common Prayer which was at the center of the Austen family’s corporate and household worship. One passage from one of her prayers reflects how deeply and sincerely she held matters of character:

Look with Mercy on the Sins we have this day committed, and in Mercy make us feel them deeply, that our Repentance may be sincere, & our resolutions stedfast of endeavouring against the commission of such in future. Teach us to understand the sinfulness of our own Hearts, and bring to our knowledge every fault of Temper and every evil Habit in which we have indulged to the discomfort of our fellow-creatures, and the danger of our own Souls.

Such earnest humility might appear as a surprising contrast to the persona of the witty, sharp-tongued narrator who slices through all foibles, follies, and pretensions in the characters she created. But the ability to find amusement in human frailties is a virtue, not a vice, especially when the source of that amusement is one’s own world and oneself, as evidenced by Austen’s self-deprecating narrative style.

Austen would likely have been both surprised and amused at the cult status she has achieved two centuries after her death in 1817. To be sure, Austen took delight in the modest fame (and income) her work brought during her short lifetime. A lifelong lover of literature, Austen approached writing with studious intensity, drafting and revising most of her novels for years before they were published. She’d have made great sport of the fact that some of scenes and memes most popular among her fan base today come not from her novels but from their many film adaptations which, with few exceptions, largely misunderstand (or misrepresent) her work.

Contrary to the contemporary mythos, Austen’s novels aren’t about love, romance, and marriage, although plenty instances of all these fill the pages. No, Austen’s novels are about character—that is, virtues and vices, and what those character traits look like when they are tried in the crucible of life. Love, romance, and marriage are simply the particular tests through which character is revealed. Life offers infinite tests, of course, but Austen, like all good writers, wrote about the world she knew.

It may bristle the literary purist to think about a novel being “about” something. Of course, Austen’s novels are first and foremost works of literary art that simply do what art always does: interpret and re-create human experience. As works of art, the novels are foremost to be read, re-read, and enjoyed.

At the same time, Austen was writing in a particular genre, a tradition she inherited from the Neoclassical writers of the earlier 18th century whom she and her family read and adored. Her works fall within the genre called the novel (or comedy) of manners, a form of satire that ridicules the habits, mannerisms, and morals of the upper classes. As with all satire, this mockery is intended to correct the vices and follies targeted. While Austen offered pointed social critiques—most often of the social and legal traditions that made women economically vulnerable and therefore entirely dependent upon the benevolence of men, for example—her main focus was on how individual character can contribute to or detract from one’s happiness within one’s given social circumstances.

Austen’s approach to virtue, or character, is solidly Aristotelian: Virtue is a trait that moderates between excess and deficiency, between, for example, pride (too much self-regard) and prejudice (too little regard for others) or between sense (reason) and sensibility (emotion). It is the virtuous life that leads to happiness, according to Aristotle—and Austen.

The English word “happiness” comes from a Greek word that signifies not mere happiness of the fleeting sort, but the happiness of well-being, flourishing, and good spirit that can also be translated as “the good life.” The word “happiness” appears in Pride and Prejudice, for example, more than 70 times, sometimes signifying the ephemeral sort of happiness produced in romantic girls by the arrival of eligible soldiers in town. But happiness most significantly appears in the context of marriage, the desired state for nearly all those inhabiting Austen’s social world. Determining the suitability of a marriage partner requires, in Austen’s view, the virtues of prudence, wisdom, and humility: prudence to make a match that will work personally, socially, and economically; wisdom to judge accurately one’s own character as well as the characters of others; and humility sufficient to admit and correct when one’s judgment turns out to be wrong.

The level of happiness Austen’s characters attain (again, often in marriage) correlates generally with the virtue they possess. In Sense and Sensibility, for example, Elinor Dashwood eventually corrects her excess of “sense” by learning to acknowledge and express her “sensibility.” In contrast, her overly-emotional sister Marianne, learns to give her passions less rein and to exercise more reason. Emma Woodhouse in Emma is benevolent but overconfident in her own judgments. Being humbled in the latter allows her natural goodwill to be exercised virtuously. Similarly, Elizabeth Bennet, who is the wisest and most discerning member of her family, learns that even her “fine eyes” can make errors, and in making this painful discovery, she expresses the entire theme of Pride and Prejudice: “Till this moment I never knew myself.”

“Know thyself” is a classical ethical mandate, and each of Austen’s novels follows the main character coming to know herself better, which is necessary for true happiness. Knowing oneself requires not only humility, but the exercise of reason as well.

“Reason” (or its variations) appears even more frequently in Pride and Prejudice than the word “happiness.” Elizabeth Bennet’s errors in judgment are reasonable ones. But when reason leads astray, it is also reason that can correct course. In one of the final scenes of the novel, in which Elizabeth and her suitor Mr. Darcy are reconciling various details of their previous, mutual misunderstandings, Elizabeth replies wittily to Darcy’s explanation, “How unlucky that you should have a reasonable answer to give, and that I should be so reasonable as to admit it!” Austen understands reason to be central to virtue. But reason, too, can be relied on excessively when absent other virtues, thereby becoming a vice, as illustrated by Elizabeth’s pedantic sister Mary who draws abstract knowledge from books without adding to it the real-life experience required to turn rational judgments into true wisdom.

Even the most likeable, most virtuous characters in Austen’s stories are flawed. What makes them most likeable and virtuous is their willingness to grow in virtue and to be reasonable in the face of error. The best of Austen’s characters display the Bible’s admonition in Philippians 4:5 to make their reasonableness evident to all. Austen’s own character, as revealed through the narrators she creates, perfectly embodies the fruit of the Spirit described in Galatians 5:22-23: love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Indeed, one could read all of Austen’s novels through this rubric and come away with one’s own Christian character expanded.

And this is what makes Austen such a brilliant novelist as well as a keen moral philosopher. She doesn’t just tell the reader about such characters. Instead, she shows through narrative technique the inner workings of a character’s mind a willingness to be changed in order to follow truth wherever it leads. Using dialogue both between characters and within a character’s inner thoughts, Austen takes the reader on a vicarious search for truth and, ultimately, self-knowledge. The careful reader can’t help but to grow in character simply by coming along the character’s own virtue-building, truth-seeking journey.

More subtly, but of great ethical significance, Austen shows that people need not be malicious or ill-intended in order to make disastrous or life-altering misunderstandings and mistakes. It is how one responds in realizing such a mistake or misunderstanding that is the test of real character. If there are two kinds of characters in Austen’s novels, they are those who allow themselves to be persuaded of the truth even when the truth seemed previously to be otherwise—and those who don’t.

Persuasion (which, not coincidentally, is the title of one of Austen’s novels) is not only a rhetorical act but an ethical one, too. The subtlety of the language, dialogue, and manners in Austen’s novels reflects the subtlety of effective but patient persuasion. I expect it is this quality—both the nuanced writing style and the nuanced moral content—that makes Austen’s works seem so quaint today.

Indeed, the sheer civility—often in the form of simple attentiveness—that is required and cultivated by choosing gentle persuasion over dominance strikes today’s reader today as strange. But that civility—that willingness to persuade and to be persuaded—is what we need most from Austen 250 years later.

In a cultural moment increasingly defined by the language (and actions) of pride, prejudice, arrogance, degradation, and domination, and by the lack of both sense and sensibility, we can benefit much from reading Austen—not for the love, romance, and marriage (although that is all delightful!), but for what Austen’s novels are really about: character.

Mark Kendall: America ‘Looking for Jesus’

For nearly 70 years a Nativity-inspired tableau has been a regular Christmas fixture in Ontario, California. Despite vandalism and legal attempts to have the figures removed from public property, they remain. It all might be a lesson for an American that simultaneously may be losing religion but that also might be suffering from an overbearing sense of religion in the public square, Mark Kendall writes.

The wise men outlasted the wise guys, though, and for nearly seven decades the scenes have been faithfully repaired, reassembled, and displayed for all to see every Advent. The survival and enduring appeal of these displays of faith offer hope for those of us who believe Christianity should have a place in the public square and not be confined to the most private realms. But it would be a mistake to interpret the Nativity scenes’ story as some sort of culture-war triumph. In our current societal context, the existence of these tableaus is more countercultural and out of the ordinary than an overbearing imposition from the dominant religion.

I’ve come to find these scenes a reassuring and steadying presence in my year-end life, pointers to deeper meaning in this season. The hard question in our cultural and political moment is whether the themes of humility, mystery, and God-with-us conveyed in these displays can get through when, far beyond this one boulevard, Christianity in America is at a confounding crossroads. On the one hand, therole of religion has been declining in many Americans’ lives. Concurrently, a significant segment of Christians are asserting a cultural-political vision of the faith that focuses on attaining earthly power. From a Christian vantage point, there is not much to be gained if Nativity scenes like this are simply quaint markers of a fading cultural heritage or empty symbols embraced by politics-first Christians who have lost the message the symbols are meant to convey.

Another Sunday Read

- Poet Emma Lazarus is remembered for her poem “The New Colossus,” inspired by the Statue of Liberty and the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” she welcomed. But for Arc, Stuart Halpern argues we should also remember her for her poems about Hanukkah, which begins tonight. “Emma Lazarus’s pride in millennia-old Jewish stories was, in light of her background, unexpected. Born in New York in 1849 to an assimilated Sephardic Jewish family, she observed Christmas and spent Friday evenings not in synagogue but at the elegant salons of Richard and Helena Gilder, the editor and illustrator of Century magazine. The prolific and widely admired writer and translator, whose professional circle included Ralph Waldo Emerson and James Russell Lowell, couldn’t help, however, but notice the Jew-hatred in the ether. ‘Within recent years,’ she observed in Century, in words that read like today’s headlines, ‘in our schools and colleges, even in our scientific universities, Jewish scholars are frequently subjected to annoyance on account of their race. … In other words, all the magnanimity, patience, charity, and humanity, which the Jews have manifested in return for centuries of persecution, have been thus far inadequate to eradicate the profound antipathy engendered by fanaticism and ready to break out in one or another shape at any moment of popular excitement.’ Years after Emma’s death at age thirty-eight, her own sister, Annie Lazarus Johnston, who had converted to Anglican-Catholicism, denied a publisher’s request to publish Emma’s Jewish poems. … Even in her young adulthood, Lazarus discerned the need for Jewish political renewal and the protection of her coreligionists’ liberties. Inspired by George Eliot’s proto-Zionist Daniel Deronda (1876) and horrified by a wave of pogroms in Russia, she sensed the need for modern Maccabees to arise. The ‘Feast of Lights’ (1882) depicts the menorah as a metaphor for the splendor of the Maccabean spirit she sought to write into existence.”

Religion in an Image