Two small populist parties dramatically increased their number of seats in the upper house: The Democratic Party for the People (DPFP) went from five to 22 seats, and Sanseito (“Participate in Politics”) went from a single seat to 15. Their gains seem to have come almost entirely at the expense of the LDP, with the main opposition party, the Constitutional Democrats, merely holding steady at 38 seats.

Both of the emerging parties are led by charismatic political celebrities with large online followings. The DPFP’s leader, Yuichiro Tamaki, refers to himself as “neither left nor right,” and campaigned on a slogan that rivals “the rent is too damn high” in its bluntness: “Increase take-home pay.” At 56 years old, Tamaki is young compared to the leaders of the main parties, who are both 68. He frequently criticizes the “silver democracy” of Japan, where seniors, at 30 percent of the population, are the most powerful voting bloc.

Tamaki, however, is the relative moderate. Sanseito’s leader, Sohei Kamiya, started his party in 2020, shortly after launching a YouTube channel which gained traction for spreading conspiracy theories about vaccinations and “Jewish capital.” He has positioned himself as the loudest critic of Ishiba from the right.

Kamiya gained momentum in the last few weeks of the campaign by loudly criticizing foreigners, whether they be guest workers from Korea and the Philippines or boorish Americans, for allegedly taking advantage of Japanese citizens while disrespecting their culture and customs (one wonders if he had a certain State Department official in mind). More combative than Tamaki, his slogan was “Japanese First!”

Younger voters flocked to both parties. According to an exit poll by Kyodo News, roughly half of voters under 40 cast a ballot for either the DPFP or Sanseito, even as both parties combined for around 28 percent of the overall vote. Younger people are especially angered by Japan’s weak wage growth, which has lagged behind inflation, and the rising price of rice, a metric that possesses enormous symbolic significance in Japanese politics.

Tamaki appealed to these voters by calling them “forgotten people,” advocating for cutting the consumption tax, an important source of government revenue, and for spending more on the young with “education bonds.” Kamiya took a more aggressive attack, accusing immigrants of taking away jobs from young Japanese people. While it’s true that previous leaders increased immigration quotas to address labor shortages, the foreign-born population of the country is still only 3 percent, far below most developed economies.

For Kamiya and his supporters, however, even 3 percent is too much. Sanseito campaigned on excluding non-Japanese residents from welfare and cracking down on illegal immigration. Globalization is the “reason behind Japan’s poverty,” Kamiya has claimed.

But while the party’s anti-immigrant stance and avowedly Trumpian style have garnered much of the attention from foreign press, experts who spoke to TMD cautioned against viewing the election as a referendum on migration. Immigration wasn’t close to the top issue for the general public, almost half of whom cited either rising prices or public welfare as the biggest factor in how they would vote in a poll from early July. Ishiba and his Cabinet’s approval rating also stands at 23 percent, indicating that at least some voters saw their choice of a third party as more of a vote against an unpopular incumbent than for a specific program.

New parties “can capitalize on this sense of malaise, fatigue, disillusionment with mainstream politics,” John Nilsson-Wright, a professor of modern Japanese politics at the University of Cambridge, told TMD. But it remains to be seen whether the upstarts can become established players in their own right, he argued.

After all, both the DPFP and Sanseito remain minnows compared to the wounded leviathan of the LDP, still the largest party in the House of Councillors by a wide margin. Unless he loses a vote of no confidence, Ishiba can still continue in his current post. “That’s right,” he said Sunday, when asked at a press conference if he intended to remain prime minister. It’s possible for Ishiba to keep his position and govern from the minority, provided that he’s willing to scramble for compromises with other parties.

Keeping other parties on board would be difficult, but not impossible. “The key issue is whether the opposition would be minded to support a no-confidence vote,” said Nilsson-Wright. But Ishiba has shown that he’s capable of cobbling together the votes for a majority on an issue-by-issue basis, Nilsson-Wright pointed out. Japan’s latest budget, passed in March, was the product of Ishiba negotiating with smaller parties for their votes, including by delaying a planned increase in a cap on medical expenses.

Ishiba’s political fortunes got a major boost late Tuesday night, when President Donald Trump announced the U.S. and Japan had agreed on a framework for a trade deal. “I just signed the largest trade deal in history; I think maybe the largest deal in history with Japan,” Trump said at a reception with congressional Republicans. “They had their top people here, and we worked on it long and hard. And it’s a great deal for everybody.”

The deal will place a 15 percent tax on goods imported from Japan, and the country will invest $550 million into the United States and open its markets to American goods like cars and rice, according to Trump. Crucially for Japan, the deal also will set tariffs on its auto exports, which are subject to a separate tariff schedule, at 15 percent. It will give Japanese carmakers an edge over those in other countries, which have faced an additional 25 percent tariff since April.

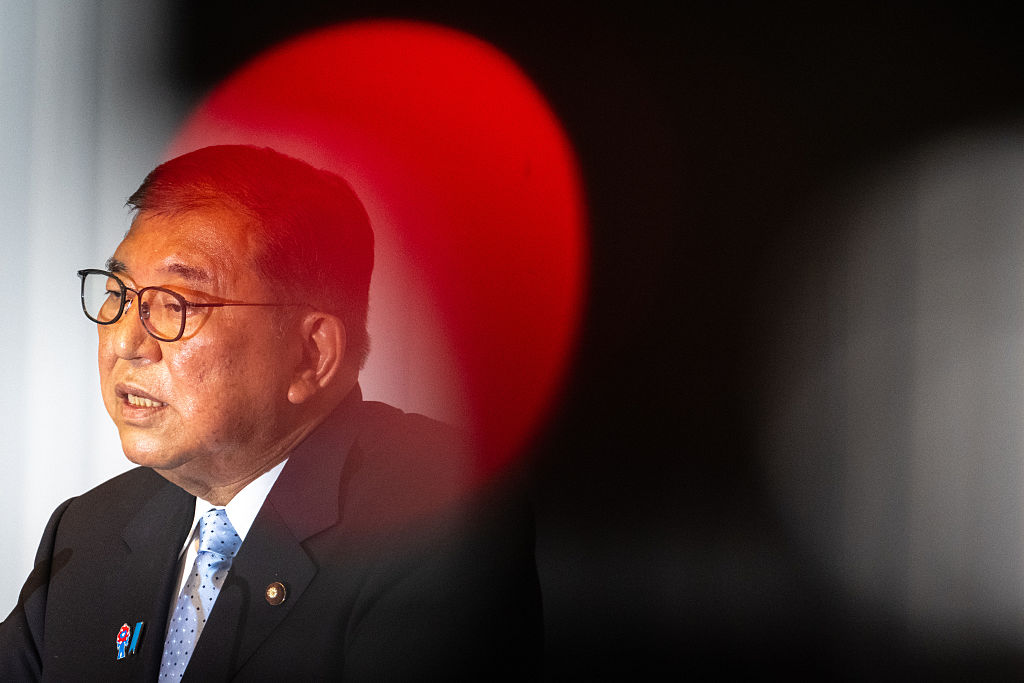

Japan had been facing an August 1 deadline that would have triggered a 25 percent tariff on its imports, and little progress toward a deal had seemingly been made, even after six separate visits to Washington by Akazawa Ryosei, the country’s minister of economic revitalization. For his part, Ishiba viewed the negotiations as “a battle for our national interest. We will not be taken lightly.”

The agreement will undoubtedly help Ishiba in his bid to retain power, but voices within the LDP have begun to call on him to take responsibility for the electoral defeat. “The prime minister and secretary-general both say the party is still the largest party. But instead of puffing our chests, we should be accepting the heavy truth that we couldn’t achieve the goal of reaching a majority,” Farm Minister Shinjirō Koizumi said Tuesday.

An all-party meeting is slated to be held in the coming weeks to discuss the election results. As Ishiba tries to hold on to his job, his rivals—both inside and outside his party—are circling.

One of those rivals, Tamaki, certainly thinks that the LDP’s days in power are numbered. “In corporate terms, losing all three—the Lower House election, the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election and the Upper House election—is like being in the red for three quarters straight,” he declared on Monday. “It is unthinkable for no one to take responsibility.”