You who build these altars now

To sacrifice these children—

You must not do it anymore.

A scheme is not a vision,

And you never have been tempted

By a demon or a god.You who stand above them now,

Your hatchets blunt and bloody,

You were not there before,

When I lay upon a mountain

And my father’s hand was trembling

With the beauty of the word.

Leonard Cohen

/ “The Story of Isaac,” 1969

CHARLES TOWN, West Virginia—Here on the not-at-all-mean streets of Charles Town, West Virginia, where there are antiques shops and upmarket coffee places with pop-Christian praise music on the stereo and advertisements for nice apartments in the shop windows on the main street and fine old municipal buildings, and blocks of sturdy stately Victorian homes, the sidewalks are far from deserted, and if not exactly teeming or bustling with pedestrian traffic, then certainly far from abandoned as they are in so many other Appalachian downtowns, and so walking around on a bright brisk weekday morning with your cappuccino past the Abolitionist Ale Works and Pour Choices Wine and the storefront missionaries handing out food to the needy who already are lined up outside, you can observe a fairly generous and representative selection of both kinds of white people—yoga-mat whites and Marlboro Light whites—while the smell of fresh and no doubt optionally gluten-free baked goods in the air can be understood as the olfactory aspect of the literal air of gentrification settling over the place, which is only about an hour’s drive from the prosperous Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, the federal megapolis that is slowly but steadily incorporating bits and pieces of West Virginia into the asphalt sprawl of what I guess we can just go ahead and start calling Leviathan, the officers and agents of which require new bedroom communities with a CVS and a Starbucks and surely a Whole Foods not far behind however much the locals complain about the newcomers driving up the cost of living, the same old exurban thing, all of which is starting to make me think that maybe I have chosen the wrong place to go hunting for the ghost of John Brown.

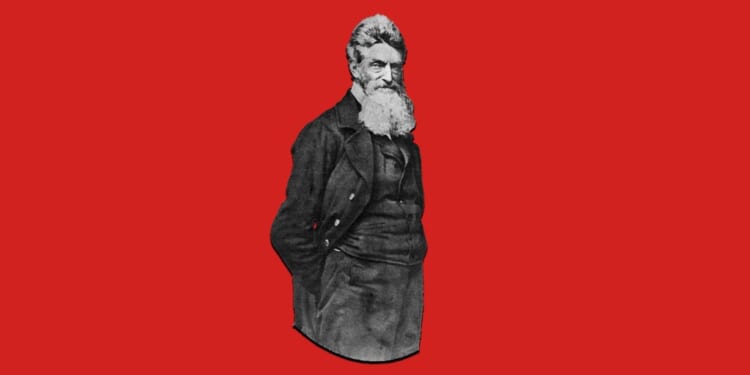

I am not demanding a vision: Sharps rifle in one hand, Bible in the other, prophetic beard, halo, blood on his boots, radiating righteousness, black wings of vengeance. No, of course not—while that may be what I want, it is not what I expect. But I was not expecting gluten-free scones and generally well-scrubbed good commercial order and two hours of free parking and hardly a whisper of what happened here. That Americans at large are only passingly familiar with John Brown’s story is undeniable: A local historian tells me that many visitors to Charles Town are surprised to learn that John Brown, who hoped to launch a slave rebellion, was white.

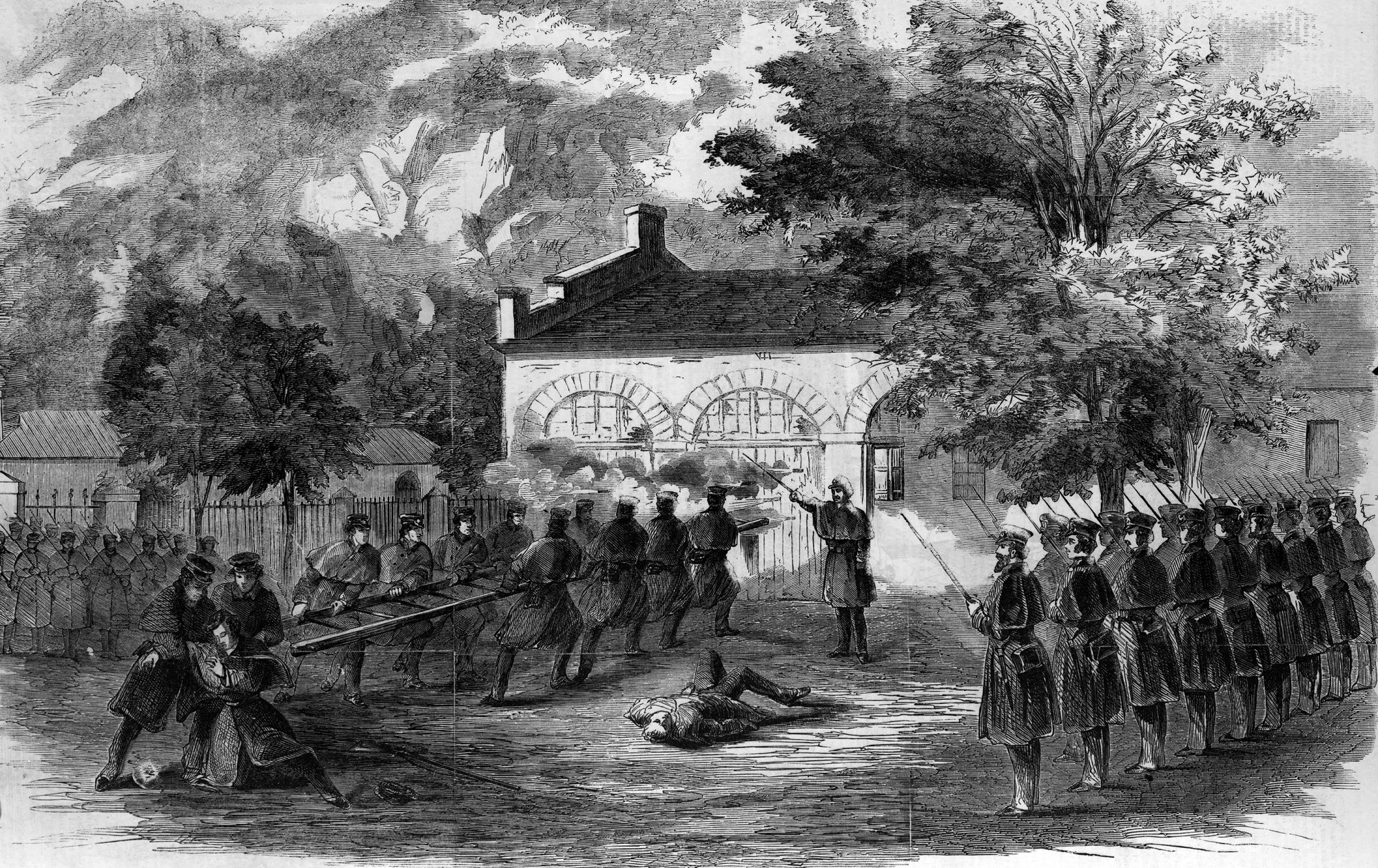

Thursday is the anniversary of the attack on Harpers Ferry, in which Brown and his band of radical abolitionists endeavored to seize a federal arsenal and inspire a slave revolt—an attack that was, depending on whom you ask, either a “dress rehearsal” for the Civil War or, in effect, its opening shots.

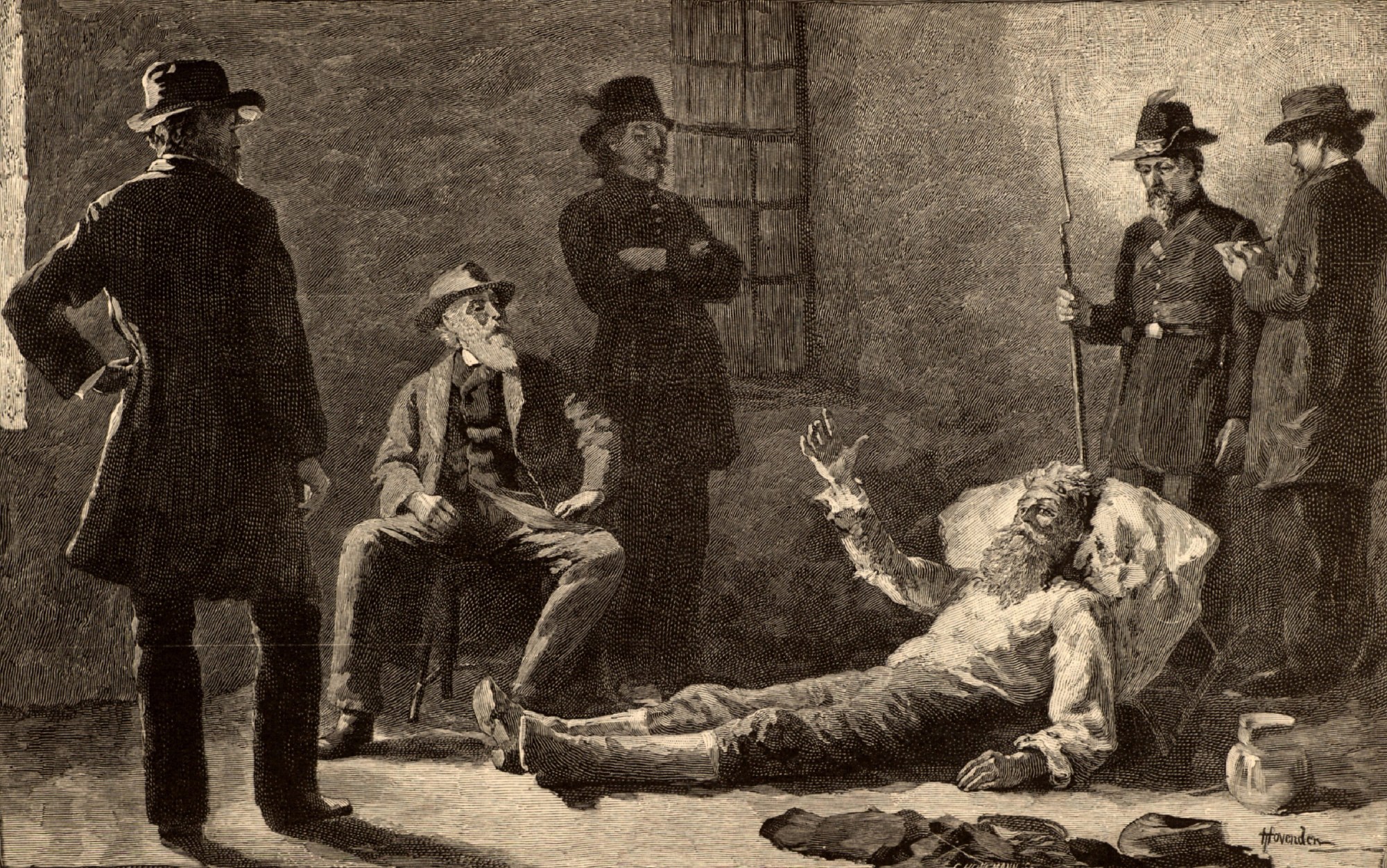

John Brown’s body lies a-moldering in the grave, as the famous song (you know its melody as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”) tells it, but that site is way far away in North Elba, New York, where he had once been part of a racially integrated colony; Brown’s most famous exploits were carried out down the road from Charles Town at Harpers Ferry and, most infamously, 1,200 miles away at Pottawatomie, Bleeding Kansas. But here in the seat of Jefferson County is where Brown was jailed, tried, and hanged for treason, the first American to suffer such a fate—but hanged under Virginia law rather than as a federal matter, in order to … expedite the proceedings, if you know what I mean and I know that you do: Only 45 days passed between Brown’s arrest and execution. The people who hanged him, who would soon being “levying War” against the United States of America, had the gobsmacking audacity to charge Brown with treason to the state of Virginia, which in less than two years would host the rebel capital of the slave power; Brown argued that he could not commit treason against Virginia because he was not a Virginian—Q.E.D.

About the murder charges, he had less of a plausible argument.

The post office here stands where the jail once stood, and some of the rubble from that structure was incorporated into a monument. You can go down to the local museum and see the wagon in which John Brown and his fellows were hauled off to their hanging, an item that the curator identifies as the most popular artifact in the collection. I’d have guessed it would have been the rifles from the Harpers Ferry arsenal: All red-blooded Americans love guns and the Bible, and we have been known to go spelunking dimly around in the latter in search of a warrant for using the former—and, to that extent, John Brown was a very familiar American type, like Patrick Henry or David Koresh.

I am not sentimental, but I do get funny little feelings about places sometimes—I have never been inside Ford’s Theatre, for example, and I always feel a little sick walking by the place. But John Brown does not seem to have left very many metaphysical footprints here. There are signs—I mean, literal signs: “JEFFERSON COUNTY COURTHOUSE WHERE JOHN BROWN WAS TRIED. In this courthouse, John Brown, the abolitionist, was tried and found guilty of treason, conspiracy, and murder. He was hanged four blocks from here on December 2, 1859. Visitors are Welcome.”

But not the kind of signs I am looking for, I guess.

As advertised, four blocks away, where the infamous if needful deed was done, stands the Gibson-Todd House, another of those stately Victorians, this one built by John Thomas Gibson, who led the Jefferson County militia in the first armed response to Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry, which began on October 16, 1859. Gibson handled security for the hanging and later became mayor of Charles Town. In attendance at Brown’s death were future Confederate generals Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, and—plainly visible in one photograph—a certain John Wilkes Booth. Gibson built a splendid house on the place where Brown was put to death, possibly (this is the view of some locals) in order to keep the place from becoming a pilgrimage site for Brown’s admirers. Standing there, you might not get much of a feel for the spiritual climate of the 1850s, but you can read the shifting political winds of the 20th and 21st centuries: In 1932, the Historical Society of West Virginia put up a very neutral-sounding plaque, reading: “WITHIN THESE GROUNDS A SHORT DISTANCE EAST OF THIS MARKER IS THE SITE OF THE SCAFFOLD ON WHICH JOHN BROWN, LEADER OF THE HARPERS FERRY RAID, WAS EXECUTED DECEMBER THE SECOND, 1859.” A plaque put up in 2025 takes a rather more definite view of the deaths of Shields Green and John Copeland Jr., fellow abolitionists and raiders—black men—who were hanged alongside Brown: “Abolitionists Shields Green and John Copeland Jr. were sacrificed at the gallows on December 16, 1859 for their pursuit of freedom for all Americans. Young Green and Copeland were two of the five African American men who participated in the revolt against slavery along with John Brown Harpers Ferry in 1859.” It seems that many Americans, at least the minority who are familiar with the case, are more comfortable thinking of Green and Copeland as freedom fighters, men who had more in common with Alexander Hamilton or Crispus Attucks than Timothy McVeigh or Charles Manson.

Something about John Brown still makes us a little nervous.

Almost everybody I talk to here—everybody who is speaking in some official capacity—is very, very careful when discussing the legacy of John Brown. “Controversial” seems to be the safe word they have all agreed to adopt. Some controversies stay controversies—and what to think about John Brown is one of the enduring ones.

Son of the South William Faulkner famously insisted: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” In that Green-Copeland plaque from 2025 it is impossible to miss an echo of the Black Lives Matter protests from a few years before it was put up. And I am here walking around talking to people about John Brown and the question of political violence two weeks after Charlie Kirk’s memorial service, which included brandished crucifixes and declarations of war on behalf of the right-wing provocateur and social-media figure assassinated by a very-online degenerate with a vintage Mauser M98. “The light will defeat the dark,” declared Stephen Miller, the mayonnaise-addicted Nosferatu who surely would be personally inconvenienced by the triumph of the light, should it come to pass. “We will prevail over the forces of wickedness and evil. They cannot imagine what they have awakened. They cannot conceive of the army that they have arisen in all of us, because we stand for what is good, what is virtuous, what is noble.” FBI Director Kash Patel, who was sworn into office with his hand on the Bhagavad Gita and apparently having forgotten which religion he supposedly practices and which entirely different religion was associated with Kirk’s faith-based entrepreneurship, declared, in heathen fashion: “See you in Valhalla.” Donald Trump showed up to praise Kirk as a “martyr” and then casually announced: “I think we found an answer to autism.” Praise … Odin, I guess? Or Shiva or maybe Western civilization or RFK Jr. or Whomever? Let the God of All-Natural Homeopathic Herbal Alternatives to Tylenol be God.

It is a funny thing, that old-time American religion. For a time, John Brown belonged to a Congregationalist church in Hudson, Ohio. He attended a prayer meeting there following the death of abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy, who died defending his printing press from a mob of slavery supporters. Brown apparently said little or nothing until the end of the meeting, at which point he stood up and spoke: “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

Unlike those show ponies angling for future Fox News gigs at Charlie Kirk’s memorial service, John Brown meant it. He was that most dangerous and terrible sort of American: a believer.

Now, my countrymen, if you have been taught doctrines conflict with the great landmarks of the Declaration of Independence; if you have listened to suggestions which would take away from its grandeur and mutilate the fair symmetry of its proportions; if you have been inclined to believe that all men are not created equal in those inalienable rights enumerated in our charter of liberty, let me entreat you to come back. Return to the fountain whose waters spring close by the blood of the revolution. Think nothing of me—take no thought for the political fate of any man whomsoever—but come back to the truths that are in the Declaration of Independence. You may do anything with me you choose, if you will but heed these sacred principles.

Abraham Lincoln

/ Lewistown, Illinois, 1858

George Washington was the father of his country, pater patriae, but he had no children. There was no George Washington Jr. dodging musket balls or freezing his toes off at Valley Forge. Yet Gen. Washington did take a paternal attitude toward the men who fought under him, and the famously austere general wept when he said goodbye to his comrades at Fraunces Tavern. John Brown, a father of 20 who outlived all but eight of his children, left three dead sons on the battlefields of his war of liberation: one at Osawatomie in 1856, two at Harpers Ferry. Another escaped to exile in sunny California, thereby adding another great American archetype to the Brown family collection. Brown’s first wife died in childbirth, with Brown’s seventh child, another son, dying with her. Abraham Lincoln had four sons and lost two of them before his own assassination: 3-year-old Eddie died of tuberculosis in 1850, and then 11-year-old Willie was lost to typhoid fever while Lincoln served in the White House. (A third Lincoln son, Tad, died a few years after his father at 18 years of age.) It was the most ordinary thing. Fathers lost sons all the time.

These were men who were close to grief, who understood its true character and knew its seasons, intimately acquainted with the fickleness of Fortune. It left them with a peculiar—certainly peculiar from the point of view of Anno Domini 2025—combination of generosity and hardness. More than 1 million Americans died as a result of the Civil War, including some 700,000 soldiers, but the commander in chief of the Union forces remained capable of feeling those casualties one at a time. As Lincoln wrote to the young daughter of an old friend who died in combat at Coffeeville: “In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it. … You cannot now realize that you will ever feel better. Is not this so? . … I have had experience enough to know what I say.”

The God of the Old Testament stayed Abraham’s hand and spared Isaac. But “Nature and of Nature’s God,” as Thomas Jefferson addressed the Almighty, cut a brutal swath through the lives of John Brown and Abraham Lincoln and everyone around them. (That is what Nature and Nature’s God does.) At Pottawatomie, John Brown and his band pulled a father and two of his sons out of their beds and put them to death as the wife and mother listened to the dying screams of her husband and children. Abraham Lincoln had a great many mothers’ sons on his conscience. And maybe that is one of the important ways in which the 19th century more closely resembled the ancient world than it does our own time: John Brown’s bloody campaign—his high-minded spiritualized violence—shocks the modern sensibility even more than it did that of the 19th century because we are less accustomed to intimate losses. As an admirer of John Brown’s (I write these words under his portrait) I do not like to think of this, but: If you want to understand the apparent inhumanity of, say, Hamas or the Taliban, start with John Brown. Or Timothy McVeigh or the guy who shot Charlie Kirk or Cliven Bundy or the Unabomber—every bush-league gormless misfit with an AR-15 and a couple of full magazines of 5.56mm and some toxic pent-up sexual frustration thinks he is John Brown. Nobody ever thinks he is John Hinckley Jr.

The John Brown controversy still commands our attention because John Brown is dead but the issue he raises isn’t. Some people think they have a really, really good reason for killing a person or a 100,000 of them or a million—and not all of them are wrong, as you could glean from a halfway competent biography of Dwight Eisenhower or Ulysses Grant.

Or go straight to the uncut stuff and open your Bible.

That the great man of the 19th century was a bearded, practically biblical patriarch by the name of “Abraham” feels almost preordained. (Here, my Calvinist friends may smile.) The parallels were not lost on the 16th president’s admirers and partisans, who marched into battle singing “We Are Coming, Father Abraham!” So many sons sacrificed under the hesitant blade of that American Abraham—the God of Democracy is a God even more jealous than the God of the Old Testament—so many sons and then “300,000 more,” as that perversely jaunty song reports the data. Lincoln himself appreciated the biblical overtones of his times, and perhaps he even had an idea of what that might mean for him personally. In contrast to the thoroughly pagan political deification of George Washington, whose imperial apotheosis is depicted in that ghastly Constantino Brumidi painting on the Capitol dome, Lincoln became the ultimate great atoning human sacrifice of the Civil War—shot on Good Friday, no less, in case History wasn’t making the point pointy enough for you. The clergymen of his day got the point, and many of the Sunday sermons following Lincoln’s death had St. Paul’s words thundering from the pulpit: “Without the shedding of blood is no remission.”

If you have the right kind of American eyes, it may seem equally preordained that the prophet who came before the Christly figure of that American Abraham just as inevitably bore the name “John,” a fugitive voice crying in the wilderness, wild-eyed and full of holy terror and uncompromising, and marked for a divine appointment with Herod’s executioners. John Brown was, among other things, a former shepherd, for Pete’s sake. But there were complications and limits to the biblical parallels: John Brown’s great long patriarchal beard, familiar from the famous portraits, was a disguise—most of his life, he was clean-shaven, or at least as often as he could be in his vagrant circumstances. And when that American prophet traveled to Harpers Ferry, he did not sign his name “John” while securing accommodations for his holy insurgents—then, he was “Isaac,” presumably after the son of the free woman who ultimately would cast out his half-brother, Ismael, the son of the slave. One suspects that the choice of a nom de guerre was far from accidental. “This is an allegory,” St. Paul wrote to the Galatians. “These women represent two covenants. One covenant is given on Mount Sinai and bears children who are born into slavery … Now you, brethren, are, like Isaac, the children of the promise. … We are the children not of the slave woman but of the free woman.”

Lincoln—who belonged to no church but planned to spend at least part of his retirement in the Holy Land—was too fond of quoting Scripture, at least in Stephen Douglas’ judgment. But Lincoln understood the American context, which begins with understanding that the Declaration of Independence, even authored as it was by the unorthodox Thomas Jefferson, is a fundamentally Christian document and arguably a Puritan one at that, the implications of which for the matter of slavery could be seen as early as the drafting of the Constitution, with its provision for the abolition of the African slave trade. That constitutional settlement, as Lincoln noted in an 1859 speech in Illinois, was the work of:

representatives of American liberty from thirteen States of the confederacy — twelve of which were slaveholding communities. … These communities, by their representatives in old Independence Hall, said to the whole world of men: ‘We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.’ This was their majestic interpretation of the economy of the Universe. This was their lofty, and wise, and noble understanding of the justice of the Creator to His creatures. Yes, gentlemen, to all His creatures, to the whole great family of man. In their enlightened belief, nothing stamped with the Divine image and likeness was sent into the world to be trodden on, and degraded, and imbruted by its fellows. They grasped not only the whole race of man then living, but they reached forward and seized upon the farthest posterity. The erected a beacon to guide their children and their children’s children, and the countless myriads who should inhabit the earth in other ages.

Wise statesmen as they were, they knew the tendency of prosperity to breed tyrants, and so they established these great self-evident truths, that when in the distant future some man, some faction, some interest, should set up the doctrine that none but rich men, or none but white men, were entitled to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness, their posterity might look up again to the Declaration of Independence and take courage to renew the battle which their fathers began — so that truth, and justice, and mercy, and all the humane and Christian virtues might not be extinguished from the land; so that no man would hereafter dare to limit and circumscribe the great principles on which the temple of liberty was being built.

Fine words. Great words. Important words. Spoken just over a year before the raid on Harpers Ferry, when John Brown had decided that fine words would not do.

Brown had plans for his own kind of constitution, a “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States,” to govern his insurgent followers until the realization of that “more perfect Union” Lincoln would talk about. He raged against the “heaven-daring laws” of the slaveholding states, echoing abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison’s denunciation of the Constitution as a “most bloody and heaven-daring arrangement” between the decent godly free Christians and the idolatrous slavers.

John Brown’s moral and political reasoning was reasonably straightforward: He wasn’t launching an attack on anybody—slavery was a de facto state of war, a war of conquest launched by one group of people with the aim of oppressing another, and all he proposed to do was to fight back. This was comprehended by Frederick Douglass, who tried to talk Brown out of his program of violent insurgency: “In his eye a slave-holding community could not be peaceable but was, in the nature of the case, in one incessant state of war,” Douglass said. “To him such a community was not more sacred than a band of robbers; it was the right of any one to assault it by day or night.”

Brown’s own proposed constitutional preamble reads:

Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion—the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude or absolute extermination—in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence:

Therefore, we, citizens of the United States, and the oppressed people who, by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, are declared to have no rights which the white man is bound to respect, together with all other people degraded by the laws thereof, do, for the time being, ordain and establish for ourselves the following Provisional Constitution and Ordinances, the better to protect our persons, property, lives, and liberties, and to govern our actions.

Brown’s defense lawyer, Samuel Chilton, introduced this document at his trial—as evidence of Brown’s insanity. Chilton had hoped to keep his client off the gallows on grounds of mental incompetence, but Brown was having none of it. And whatever else Brown was, he was not a pure ideologue or an irrational religious fanatic. He was not insane, and he was not a coward who would pretend to be incompetent in order to spare his own neck. Being of sound mind, Brown almost certainly did not expect a miracle that would somehow empower him and his 21 men at Harpers Ferry to stage a successful raid presaging a general slave revolt that would crash through cotton country like a tsunami. Instead, he had described a reasonably sophisticated economic strategy—his real target was not slaveholders’ human property per se but the practical security of their ungodly property rights. “The true object to be sought is first of all to destroy the money value of slave property; and that can only be done by rendering such property insecure,” Brown wrote. That, specifically, was the goal of the raid at Harpers Ferry.

Brown, in that respect, was a classical terrorist. He knew he was almost certain to fail in achieving any substantive military goal, but that was beside the point: To establish a climate of fear is not merely to provoke a certain widespread emotional state—such a climate has practical, real-world effects. (Ask an American who remembers the country before September 11, 2001, what life used to be like.) And, like any committed terrorist, Brown could be utterly ruthless, advising that any defectors from the liberationist militia he was working to establish be hunted down and killed: “All traitors must die, wherever caught and proven to be guilty.”

Brown wasn’t the man of letters that Lincoln was, but he was a pithy writer when the spirit was on him, advising his collaborators:

Hold on to your weapons, and never be persuaded to leave them, part with them, or have them far away from you. Stand by one another, and by your friends, while a drop of blood remains; and be hanged, if you must, but tell no tales out of school. Make no confession.

John Brown was a man of God. And a fanatic. And an abolitionist. And a terrorist. But he was not—whatever the jury in Charles Town said—a traitor. “As citizens of the United States of America, trusting in a just and merciful God, whose spirit and all-powerful aid we humbly implore, we will ever be true to the flag of our beloved country, always acting under it,” he wrote in his provisional constitution. “Our flag shall be the same that our fathers fought under in the Revolution.” Both of John Brown’s grandfathers had served under George Washington. (Small world, you say? Brown’s father, Owen, once took in a young man needing employment, hiring him as an apprentice and sharing his home with him. That young man was the father of Ulysses S. Grant.) In the end, Brown was fighting for the same thing Lincoln and Grant were fighting for, even if Lincoln had made extensive—and arguably immoral—efforts to accommodate the slavers and their interests. Frederick Douglass, who knew both men and lamented Lincoln’s ceaseless appeasement, made the connection, saying of Brown:

His zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine. It was as the burning sun to my taper light. Mine was bounded by time; his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him… . The armies of the nation have found it necessary to do on a large scale what John Brown attempted to do on a small one.

John Brown’s war was Abraham Lincoln’s war and Frederick Douglass’s war and America’s war—yours and mine.

“In 2009, the park sponsored a seminar commemorating 150th anniversary of the raid, and one of the topics was ‘Madman or Martyr?’ And it was very obvious from the passion how even 150 years later, John Brown and his activity were still able to generate a great deal of feeling on both sides of the issue. I think that’s the beginning place.”

Doug Perks, who recently retired as the historian of the Jefferson County Museum, is the sort of person Edmund Burke was talking about when he wrote about the “little platoons” that make a decent liberal society possible. He spent his career telling the important stories of the place he calls home, and he got started early: As a Tenderfoot Scout in 1959, he worked on a public-service project building a façade of John Brown’s fort for a reenactment of the raid on its centennial. “That’s where I caught the bug,” he says. Then came the centennial of the Civil War and a reenactment at Antietam. “There was a vendor who had a shop at the top of the Bloody Lane, and I bought a bullet that they guaranteed had been found at the Battle of Antietam,” he says with a chuckle. “I wonder how many millions of those they sold. There was a fellow at Harpers who had a booming business selling John Brown’s pikes, probably enough of them to stretch across the United States.”

In Perks’ view, John Brown’s story is necessarily caught up in the story of the Puritans and the Pilgrims. “I think you need to start in Europe,” he says. “Stop and think about it: Why would you get on a boat with hundreds of other people and sail across the stormy Atlantic Ocean and go to a land where there were no 7-Elevens and no established farms—territory unknown, climate unknown—with the anticipation of making a new life? What motivates people to do that? Why in the world would you risk everything to do what they did? Start there. That’s where you find the motivation—that’s really how the spirit of this country grew.” And then, he says, the student of American history can stir in the rest of the ingredients: the interaction between the newcomers and the Indians, the evolving relationship between the Old World and the New World colonies, the preexisting relationships between the European powers and the African nations whose people would be commodified by the slave trade. John Brown’s story doesn’t begin in Harpers Ferry or with that solemn declaration in the Congregationalist church in Hudson among his fellow abolitionists—because it isn’t John Brown’s story.

The Pilgrims, Perks says, were people who were “willing to make whatever sacrifice they had to in order to accomplish the goal of what they believed.” In the same spirit, he says, “John Brown knew that slavery needed to come to an end. He was willing to do what he did. He sacrificed members of his own family, his fortune, and his own life for that cause.”

John Brown sacrificed his own sons, three of them, and plenty of other fathers’ sons, too. Mahala Doyle, the wife and mother of Brown’s victims in Kansas, sent him a letter before his hanging:

Altho vengeance is not mine, I confess, that I do feel gratified to hear that you ware stopt in your fiendish career at Harper’s Ferry, with the loss of your two sons, you can now appreciate my distress, in Kansas, when you then and there entered my house at midnight and arrested my husband and two boys and took them out of the yard and in cold blood shot them dead in my hearing, you cant say you done it to free our slaves, we had none and never expected to own one, but has only made me a poor disconsolate widow with helpless children while I feel for your folly. I do hope & trust that you will meet your just reward. O how it pained my Heart to hear the dying groans of my Husband and children if this scrawl give you any consolation you are welcome to it.

It is true that the Doyle family owned no slaves, but they were not exactly innocent bystanders: They were part of a pro-slavery militia—known at the time as “Border Ruffians”—whose aim was to overwhelm Kansas through a determined campaign of political violence in order to ensure that the state entered the Union as a slave state, thereby fortifying the slavers’ political position in Washington. They were also, according to some accounts, slave-hunters, mercenaries who ran down fugitive slaves. The local Ruffians had made a particular point of promising to murder John Brown’s abolitionist sons, who had gone to Kansas seeking to improve their personal fortunes long before their father ever set foot there. They wrote to their father asking him to send arms and supplies, and he showed up in person to deliver them—and, finally, to deliver justice as he saw it, to the Doyles and to the other Ruffians and to the slave power at large. Yes, John Brown was a terrorist—and so were at least some of his victims.

Lori Wysong, the director of the Jefferson County Museum, reports that people have come from as far away as Australia and Japan to see the John Brown collection, to look at the rifles and stand in front of the death-wagon and take in the other artifacts, inching toward a more historical understanding of the man and his cause than the one they might have absorbed from popular culture. John Brown’s myth was shaped with intention. Immediately following the raid on Harpers Ferry, Wysong says, the propaganda contest got underway, with northern abolitionists depicting Brown as a spotless martyr and southern slaveholders painting him as a sadistic villain. Those two versions of John Brown—neither quite accurate—have been circling one another like wrestlers for the better part of two centuries now.

For a time, Brown seemed destined to become a kind of stock villain, appearing as a highly fictionalized, anarchistic malefactor—think of a kind of proto-Joker—in old serials and films such as Santa Fe Trail. He takes the lead in Russell Banks’ novel Cloudsplitter and figures in Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. He is a fanatical clown in James McBride’s novel The Good Lord Bird but a more interesting and sympathetic, if still occasionally ridiculous, figure in Jason Blum’s wonderful film adaptation of that novel, with Ethan Hawke as Brown. A loosely organized network of left-wing gun owners calls itself the John Brown Gun Club. His memory is, as they say, contested.

Brown was the Devil himself for many years in Jefferson County, which, having a good deal of local slavery, was culturally and economically closer to Virginia’s plantation culture than were most of the counties that broke away to form West Virginia in 1863. (There was, in fact, a failed effort to bring Jefferson County back into Virginia after the war.) Jefferson County almost certainly would have rejected the referendum to join West Virginia if the Union army—which had no intention of giving up use of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line running through the town—had not intervened (according to local historians) by placing the majority of voters under house arrest and permitting only two friendly precincts to cast ballots. Sometimes the terrorists are on the right side, and sometimes the voters are on the wrong side.

The picture of John Brown that hangs on my wall in my home office is the one with the Mosaic beard—the prophet incognito. Below his picture is one of Abraham Lincoln; across from it is a painting of St. Jerome (an excellent portrait by Judith Kudlow and one of my most prized possessions). Next to these is a case with my Winchester rifle and a couple of No. 1 Rugers. (All unloaded, of course. The ammunition and the less lovely firearms, including the loaded ones, are kept under biometric lock.) All of this is supposed to add up to something, I suppose, but I am not sure I could really explain to you what that is, and it is my office. I think I have about the same capacity for violence and fanaticism as any other American—I am sure I could bake Vladimir Putin into a pie à la mode (de Titus Andronicus) and never lose a minute’s sleep over it—and if I have been kept from some violent extremity it surely is through no particular virtue of my own: I am very much aware of being a man with much to lose. Is there a cause into which I would throw myself, body and soul? I like to think there is.

But I think of those dead sons left on the battlefield—the Brown boys, the Doyle boys, all those uncounted Union and Confederate soldiers, the typhoid fever that (along with dysentery and measles and other infections) killed more soldiers than did rifles and bayonets and cannon all combined and that reached all the way into the White House to take the life of 11-year-old Willie Lincoln. I think of Abraham and Isaac and am, like any sensible bourgeois father with a pretty wife in a comfortable house on a safe street in a quiet little town, fundamentally repulsed by the God who would demand such a thing of anyone, much less of those who most love Him. But I also wonder whether that is my conviction speaking or only my comfort and my complacency.

Do I believe what John Brown believed?

I believe in the Golden Rule and the Declaration of Independence. I think they both mean the same thing; and it is better that a whole generation should pass off the earth, men, women, and children, by a violent death, than that one jot of either should fail, in this country.

No, I do not believe that. But, then, John Brown’s example makes me wonder whether I really believe anything at all, even Oliver Cromwell’s maxim: “Trust in God and keep your powder dry!” I live in a world in which both war and religion have been thoroughly bureaucratized and sanitized—at least at the commanding heights: Dwight Eisenhower, the great man who led the liberation of Europe from forces of genuine darkness, never personally saw combat. Our generals, like our popes, mainly write memos and attend committee meetings. We do not even have the courage of our convictions in sufficient measure to forthrightly hang such a man as John Brown in public today, preferring instead to cower behind the prison walls and pretend that what is going on in the execution chamber is some kind of medical procedure. There is much to be said for prudence and balance—if a society that has slavery has to have a John Brown, then a society that has the rule of law has to hang him. But prudence can also be a hiding place.

Frederick Douglass had a definite view of this:

Did John Brown draw his sword against slavery and thereby lose his life in vain? And to this I answer ten thousand times: No! No man fails, or can fail who so grandly gives himself and all he has to a righteous cause.

… If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery, he did at least begin the war that ended slavery. John Brown began the war that ended American slavery and made this a free republic. Until this blow was struck, the prospect for freedom was dim, shadowy and uncertain. The irrepressible conflict was one of words, votes and compromises. When John Brown stretched forth his arm the sky was cleared. The time for compromises was gone; the armed hosts of freedom stood face to face over the chasm of a broken Union; and the clash of arms was at hand. The South staked all upon getting possession of the federal government, and failing to do that, drew the sword of rebellion and thus made her own, and not Brown’s, the lost cause of the century.

John Brown died a martyr’s death. Abraham Lincoln, too. Frederick Douglass, who had endured life as a slave, surely had earned the right to die in his bed. And I suppose that the question John Brown’s defiant face on my wall at home really raises for me is whether I have earned that right and, if not, what I have to do to earn it. There are no answers here in Charles Town, and not even John Brown’s body, only the wagon they hauled him away to the gallows in.