from the where-everything-is-made-up-and-the-points-don’t-matter dept

In theory, the nice thing about having a Supreme Court is that it provides some level of legal certainty. You know how the system works: lower courts make decisions based on law and precedent, parties can appeal, and eventually the highest court issues careful, reasoned opinions that other courts can follow. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s a system.

The less nice thing is when the Supreme Court decides that systems are for suckers.

Last month we wrote about how the Supreme Court’s shadow docket had become a “lawless, explanation-free rubber stamp for Trump’s authoritarian agenda.” This wasn’t about policy disagreements. Or even disagreements about legal interpretations. It was about how the majority on the Supreme Court was using the “emergency relief” docket (the shadow docket) to issue explanation-free, unbriefed, consequential rulings (only in one direction) and then expecting anyone to know what the law actually is.

We had warned how John Roberts was guaranteeing that the Court would be kept busy all summer with these shadow docket rulings, and that is exactly what has happened. The pattern is straightforward: lower courts try to enforce existing law, the administration appeals on an emergency basis, and the Supreme Court says “okay, sure, let Trump do what he wants” with zero legal explanation. The only coherent principle seems to be “it’s okay if Trump does it.”

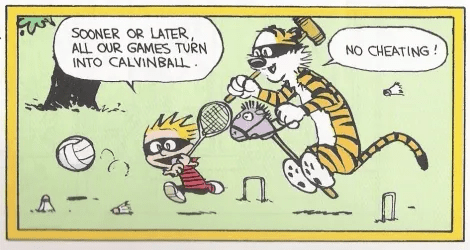

This is, let’s be clear, not how judicial systems are supposed to work. But Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson has been calling this out with increasing directness. She’s not mincing words. She’s not worried about collegiality. And now she’s given us the perfect term for what’s happening. She’s added Calvinball to the SCOTUS lexicon:

In a broader sense, however, today’s ruling is of a piece with this Court’s recent tendencies. “[R]ight when the Judiciary should be hunkering down to do all it can to preserve the law’s constraints,” the Court opts instead to make vindicating the rule of law and preventing manifestly injurious Government action as difficult as possible….. This is Calvinball jurisprudence with a twist. Calvinball has only one rule: There are no fixed rules. We seem to have two: that one, and this Administration always wins.

Calvinball, of course, is the favored pastime of Calvin from Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes. And, yes, the point is that there are no rules.

The somewhat prescient Oxford English Dictionary added it to the dictionary just a few months ago, apparently recognizing how widely it’s been used to describe courts these days. I’ve certainly been using it to describe various judicial adventures of late, so it’s satisfying to see Justice Jackson make it official.

Jackson’s diagnosis cuts deeper than just this particular case. She’s identifying a systemic problem: a Court that has abandoned legal reasoning in favor of reaching predetermined outcomes, then wrapping those outcomes in enough procedural complexity that nobody can quite pin down what the rules actually are.

It almost doesn’t matter what this case is about, because it’s the principle about how the Supreme Court is now creating massively consequential binding precedent without the basic fundamentals of a thorough judicial process with things like full briefing or oral arguments.

But just for clarity: the case itself was about whether NIH could terminate nearly a billion dollars in grants. A district court judge had said (using actual reasoning and legal precedent) that NIH had to continue providing the money it had already promised and budgeted, noting that halting such payments violated the Administrative Procedure Act’s prohibition against “arbitrary and capricious” government actions. Straightforward stuff, really.

Unlike some shadow docket rulings, there were at least some explanations given here, though nothing you’d call illuminating. Four useless paragraphs basically just say the lower court’s ruling is stayed. Then there are various concurrences and dissents (and partial concurrences and partial dissents) that make it clear nobody quite agrees on what they’re doing, though much of it involves arguing over how much precedent an earlier shadow docket ruling (with basically zero explanation) should have on later shadow docket decisions.

Which maybe should have been a hint that this is a case that needs full briefing before making such consequential decisions about it.

And the lineup underscores the point: Justice Barrett would partially grant the stay; Chief Justice Roberts with Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson would deny it entirely; Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh would grant it entirely. If you’re keeping score of this Calvinball game, that’s a three-way split on an “emergency” order, with Barrett’s split vote winning the day—exactly the kind of messy, disputed ruling that demands full briefing.

It’s like watching people argue about the rules of a game while they’re making up the rules as they go along—and their only guiding principle is “well, we know who has to win.” Which, Jackson points out, is basically what’s happening. This creates what she calls a “jurisdictional maze” where plaintiffs can challenge government policies in one court but can’t get relief in the same court—effectively gutting the Administrative Procedure Act’s protections against arbitrary government action.

Justice Jackson’s key contribution is highlighting just how lawless it all is. She calls out how she warned about how this would play out, and the fact that the majority on SCOTUS views these (again, unbriefed and mostly unexplained) rulings as binding across the country is terrifying:

I viewed the Court’s intervention then—in an emergency stay posture, while racing against a fast-expiring temporary restraining order—as “equal parts unprincipled and unfortunate.”…

As it turns out, the Court’s decision was an even bigger mistake than I realized. The Court’s reasoning in California was not only “at the least under-developed, and very possibly wrong,” id., at ___ (KAGAN, J., dissenting) (slip op., at 1), but also evidently resolved more than the jurisdictional dispute over the particular education-related grants at issue in that case. Today’s decision reveals California’s considerable wingspan: That case’s ipse dixit now apparently governs all APA challenges to grant-funding determinations that the Government asks us to address in the context of an emergency stay application. A half paragraph of reasoning (issued without full briefing or any oral argument) thus suffices here to partially sustain the Government’s abrupt cancellation of hundreds of millions of dollars allocated to support life-saving biomedical research.

The theory behind the shadow docket is pretty simple. Sometimes you need emergency relief to maintain the status quo while the regular judicial process works: full briefing, oral arguments, careful deliberation, the whole thing. The emergency docket exists so that irreversible harm doesn’t happen while everyone’s figuring out the right answer.

But what’s been happening is the opposite. Rather than preserving the status quo, the Court has been allowing—encouraging, really—irreversible changes to happen, without bothering to understand the issues or explain the reasoning.

And now they’re saying that these brain fart decisions based on zero details or due process, should be deemed the supreme law of the land? Jackson is having none of it:

The Court also lobs this grenade without evaluating Congress’s intent or the profound legal and practical consequences of this ruling. Stated simply: With potentially life-saving scientific advancements on the line, the Court turns a nearly century-old statute aimed at remedying unreasoned agency decision-making into a gauntlet rather than a refuge. But we have no business erecting a novel jurisdictional barrier to judicial review— especially when it appears nowhere in the relevant statutes and makes little sense.

This is not how judicial systems work, if you want them to remain judicial systems.

The majority is pretty explicit in their view that these unbriefed, unargued, unexplained shadow docket orders should bind everyone. Gorsuch, in his concurrence, doesn’t hold back:

… when this Court issues a decision, it constitutes a precedent that commands respect in lower courts…. regardless of a decision’s procedural posture, its “reasoning—its ratio decidendi”—carries precedential weight in “future cases.”

This is the judicial equivalent of an angry father, challenged by a child regarding a rule, retorting with “because I say so, and I’m the man of the house.”

It’s exactly how children (and aggrieved parties) lose respect for the rules.

Look, it’s entirely possible that after full briefing and oral arguments, the Supreme Court would reach the same result. That would be annoying for other reasons, but at least there would have been due process and a chance for all relevant parties to be fully heard. That’s how it’s supposed to work. You do the analysis, you explain the reasoning, you create precedent that other courts can follow.

What the Roberts Court has been doing is the opposite. John Roberts himself sided with the dissenters here, but he’s presided over a court that has decided outcomes matter more than process. The result is a system where “just give Trump what he wants” has become the only reliable principle.

Calvinball.

What was once a respected judicial system has become a comic strip punch line. At least Calvin had the excuse of being six years old.

Filed Under: calvinball, due process, emergency docket, grants, john roberts, ketanji brown jackson, shadow docket, supreme court