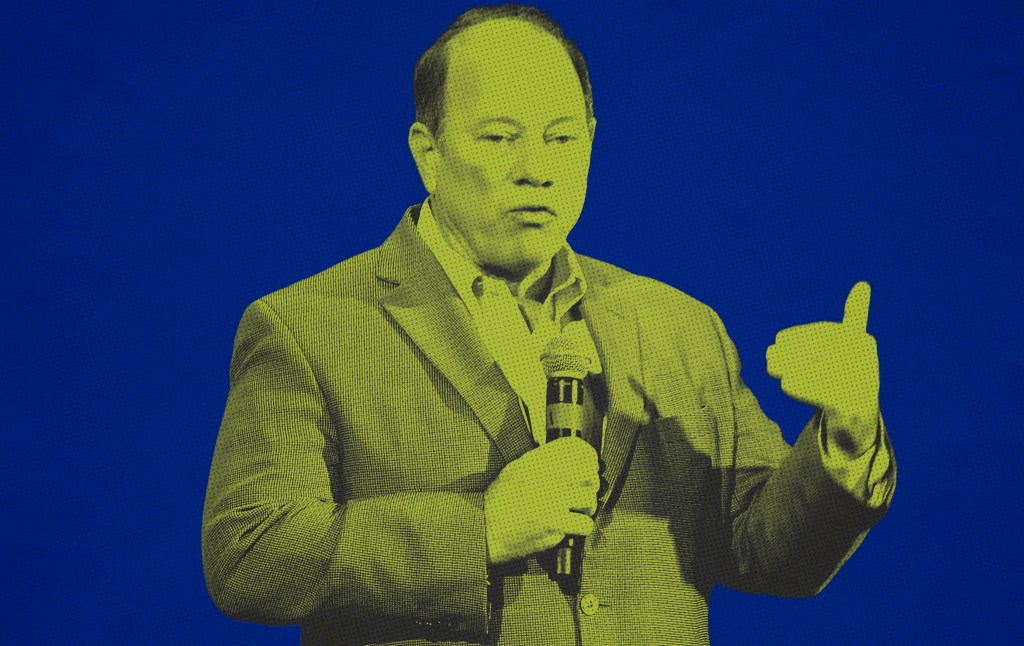

GRAND BLANC, Michigan—Mike Duggan settles into the corner booth of an upscale watering hole here on a Friday afternoon in late October for a round of questions from The Dispatch. The Detroit mayor has just hosted an hour-plus-long town hall meeting to drum up support for his independent 2026 bid for governor but, like any earnest pitchman, seems eager to keep the promotion going.

Duggan isn’t your typical, futile independent contender.

The gravelly voiced, 67-year-old former Democrat is completing his third term, having made a name for himself by turning around an iconic city that was in bankruptcy and burdened by several crises when he assumed office nearly a dozen years ago. His political challenge is nevertheless about as vast as Lake Michigan. Independents rarely win—any campaign, for any office, in any state. And that’s before accounting for President Donald Trump, and top Republicans and Democrats, all of whom will take great interest in pulverizing Duggan. The last thing the political parties want is a governor’s mansion in a crucial battleground state controlled by someone they can’t effectively influence (or demonize) ahead of the next presidential election.

Duggan is undeterred. Buoyed by healthy fundraising, albeit high expenditures, recent internal and external polling shows him trailing but competitive with the leading Democrat and Republican in the race: Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson and U.S. Rep. John James, respectively. Unlike Duggan, both must run in party primaries scheduled for August 4, 2026, and each faces opposition from multiple candidates. Asked why he’s running, the mayor serves up a plate of egg whites.

“I want to turn around the public school system in the state so that our kids can read and get a better education. I want to create an economic development strategy that attracts the jobs of the future and the tech companies, so that our young people don’t have to leave the state.” Anything else on the menu? “I want to change politics in this state; and I want to show the Republicans and the Democrats, who think they have a captive audience, that if you continue to behave this way, people will find an alternative.” (“This way” in Duggan’s telling, is chronic partisan bickering.)

Duggan, clad in slacks, a sport coat, and a blue dress shirt sans tie and vibing the Midwestern everyman, might be forgiven his hubris.

He was the first white candidate elected mayor in 40 years when he sought Detroit’s top job in 2013, winning the overwhelmingly black city in a landslide despite being kicked off the ballot on a legal technicality and running as a write-in. The mayor then completed one of the few urban turnarounds this century amid a sea of troubled Democratic-run metropolises. Even the coronavirus pandemic failed to stymie Duggan’s revitalization of Detroit, whose likely Democratic primary voters rewarded the mayor with an 84 percent job approval rating in a June survey.

On Duggan’s watch, the city has emerged from bankruptcy, crime has plummeted, quality-of-life services like snow plowing and garbage collection have improved, thousands of new jobs have been created, the population is growing, and economic development has reclaimed a deteriorated cityscape—lately including an $80 million rehabilitation of the Detroit riverfront. The scourge of abandoned houses and vacant lots, for decades the city’s claim to infamy, has yet to be completely neutralized. But Duggan has made significant progress, sparking worries the growing demand for housing may outstrip the supply of neglected homes left to restore.

Any politician with that track record might presume viability waging an independent campaign only a few have won in recent decades. How few? Since 1990, just four independent candidates for governor, running in four different states, have been successful. None of those states was Michigan. With that in mind, and considering Duggan’s record, why isn’t he running as the lifelong Democrat he was until mounting his gubernatorial bid? “It would have been a hell of a lot easier to win as a Democrat,” Duggan insisted, rejecting the premise that he’s running as an independent because opposition from the Democratic base would have guaranteed his defeat in the primary.

As a Democrat, the mayor argued, his ability to forge consensus among the two parties in both chambers of the narrowly divided Michigan Legislature would be virtually impossible—and not just on thorny political issues. Proposals that enjoy bipartisan support are often defeated because the minority party, or the party opposite the governor, is constantly looking for political advantage in the next election, Duggan said. “Here’s what I’m trying to get accomplished: How do we find common ground?”

“It is a different kind of governing and I can’t do it if I got a party label,” he asserted.

At first glance, Michigan voters don’t appear egregiously unhappy with the status quo.

Trump’s job approval and personal favorability rating was a reasonably healthy 48 percent in a Duggan campaign internal poll showing Benson favored by 30 percent of voters, James at 29 percent, and the mayor at 26 percent. The survey, fielded October 9-14, had a margin of error of plus or minus 4 percentage points. Polls from earlier this year showed Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, with job performance and favorable ratings above 50 percent. Sources tell The Dispatch not much has changed for Whitmer, who was first elected in 2018 and is term-limited.

But frustration with lawmakers and the legislative process in Lansing, the state capital, is percolating—discontent Democrats and Republicans agree exists. They blame each other.

That dissatisfaction burst wide open during the town hall meeting in Grand Blanc, a suburb of Flint in the Democratic stronghold of Genesee County. (This leafy bedroom community was recently in the news because a local Church of Jesus Chris of Latter-day Saints chapel was targeted by a gunman during Sunday services. The assailant murdered four worshipers and set fire to the facility before being killed by police.) The buffet luncheon was billed as an opportunity to learn more about Duggan’s health care agenda.

“Here’s what I’m trying to get accomplished: How do we find common ground? It is a different kind of governing and I can’t do it if I got a party label.”

Mike Duggan

But the 50-plus voters who filled up the private event space at Irene’s Craft Kitchen + Biergarten peppered the mayor with questions about his plans for addressing their myriad complaints with state and local government, issues including but not limited to tax policy, business permitting, public infrastructure, and yes, health care. Some voters, like Bill Kurkowski and Ehren Gonzales, simply wanted to express their unhappiness with a political system Democrats and Republicans have dominated since the late 1800s.

“More people than people can believe do not want the two parties doing this, like they’ve been doing for 50 years—we’re sick of it. We need someone like you,” Kurkowski, 80, told Duggan during the town hall meeting—his campaign calls these gatherings “Mike Drops”—organized by the founders of EPIC Health, operators of primary care medical clinics in Michigan and Illinois. “You’re not just a mayor, you’re a magician.” Gonzales, 55 added: “I’m with Bill. I think the two-party system just doesn’t work.” Duggan beamed.

To win, however, the mayor will have to pull voters from the ranks of those less motivated to abandon the major parties. That’s why Duggan should be especially pleased with the pledge of support from Marjorie Goza, who lives in nearby Flushing but who, along with her grandson, owns a high-end framing store in Detroit. In a brief interview with The Dispatch after telling Duggan during the town hall that she planned to vote for him next year, Goza conceded she almost always votes Republican because the GOP aligns with her conservative social positions.

“Republicans seem more concerned about the future of our country where the Democrats seem to focus on ‘this is our right’ and they don’t really think: ‘Is this really good for our country?’” Goza, who is of retirement age, said. The small business owner acknowledged she can’t be sure how Duggan would govern. “Is he going to lean more toward the Democrats or more toward the Republicans?” Goza asked, rhetorically. She’s leaning toward backing the mayor despite that uncertainty.

“I have faith in him because I’ve seen what he’s done,” Goza said. “My faith in him is what would help me to vote for him.”

She’s not the only Michigander who’s bought in. Duggan’s campaign website lists hundreds of endorsements from labor unions, religious leaders, local government officials, school board members, statewide elected officials, and former state legislators. Also on the mayor’s list of supporters: former Michigan Democratic Party Chairman Melvin Butch Hollowell; Democrat Mark Bernstein, an elected member of the University of Michigan Board of Regents; Republican former Rep. Dave Trott and former Michigan GOP Chairman Jeff Sakwa.

Duggan doesn’t sound much like a 21st-century Democrat, although he does resemble the big-city Democratic machine mayors that proliferated for decades beforehand.

Duggan has governed Detroit like the chief executive officer he was as leader of the city’s hospital system (his first turnaround success story, propelling him to the Manoogian Mansion). When city workers resisted his reforms, he threatened to fire them. When progressive activists attempted to stifle property development, he ignored them. Regulations were reduced and red tape was cut to lure employers. To improve public safety, Duggan promoted policies that prioritized arrests and convictions, befitting his experience as the former Wayne County prosecutor.

When talking taxes, economic development, and government regulations, Duggan sounds an awful lot like a Ronald Reagan-era Republican. “When you land an auto plant and 5,000 of your families moved to the middle class, that sounds to me like the kind of Democratic Party I joined in the 1980s that gave everybody a chance,” countered the mayor. His mother was a Democrat, his father a Republican who was appointed a federal district court judge by Reagan.

Which of the major political parties is he more aligned with in 2025? The Dispatch subjected Duggan to a lightning round of questions to figure out his positions on issues that tend to motivate voters’ choices.

The mayor supports abortion rights throughout pregnancy. “I’m 100 percent behind the constitutional amendment the governor—Whitmer—advocated to put the Roe v. Wade protections in the [state] Constitution.” Duggan unequivocally opposes transgender girls playing female sports. “People need to be protected against discrimination.” But: “When it comes to competitiveness in high school sports, I had two daughters who played high school basketball and soccer, and there is an unfair competition issue, and I don’t think transgender females should be able to compete in high school sports that are based on either speed or strength.”

On restricting gun rights beyond regulations already on the books: “I don’t see a need to change those laws.” On the state income tax, the mayor said: “I can’t imagine” supporting an increase. On Trump’s trade agenda: Selective tariffs could be helpful, he says. But the trade war the president instigated with Canada is hammering the state’s economy. “We are seeing layoffs in Michigan auto plants and the Canadian tariffs are a factor,” Duggan said. “But could there be tariffs on China and Mexico that could bring more manufacturing back? There could.”

On the very real possibility Trump might seek to deploy National Guard troops to Michigan cities, Duggan didn’t specify whether he would support or resist such an effort by the president. Rather, he explained how he has chosen to deal with both Trump administrations as Detroit’s mayor. Duggan’s approach is to be proactive.

He’s welcomed federal prosecutors into Detroit police precincts over the past six months to help the city address violent crime. And when a municipal arrest is made and the suspect shows up in a federal database as an illegal immigrant, Detroit honors Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s request to retrieve the individual into custody. “The Detroit Police Department does not enforce federal law. We will not stop people on the street and ask them their immigration status. That’s not our job,” Duggan said.

On the other hand, “We are not a sanctuary city,” the mayor added. “My strategy and approach is whatever’s best for the people of Detroit, the people of Michigan. People of Detroit weren’t going to benefit from me creating conflict, and so I haven’t.” Attempting to strike a middle ground on politically charged issues and Trump’s polarizing leadership is exactly what might be expected of a candidate independent in more than name only. But the Democrats and Republicans opposing Duggan are claiming, essentially, that the mayor is a fraud.

“Mike Duggan isn’t a true independent—he’s a lifelong Democrat who backed Hillary Clinton, Kamala Harris, and Joe Biden in their presidential runs, only now distancing himself because the party’s become a political loser,” James adviser Tori Sachs told The Dispatch in a statement provided by the congressman’s campaign. “As a career politician, he knows how to navigate the winds, but he can’t erase the stain of the toxic machine he helped build, wrecking Michigan and dividing America.” (The Republican Governors Association passed along a similar statement.)

The Democratic Party appears slightly more concerned about Duggan than the GOP, at least based on the consistency of attacks leveled by the Democratic Governors Association. Democrats are attacking both the mayor’s bona fides as an independent, noting his comments earlier this month defending the Medicaid cuts approved as part of Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, and doing their best to tie him to the president. One billboard The Dispatch spotted in Detroit reads: “MAGA Money ❤️ Mike Duggan.”

Democrats also are moving to undermine his viability as a gubernatorial contender.

“There isn’t this groundswell of support anywhere that I’ve seen,” Michigan Democratic Party Chairman Curtis Hertel told The Dispatch in a telephone interview. “The only reason he’s running as an independent is that he didn’t think he could win a Democratic primary. His ego couldn’t take that.” Hertel offered an additional critique Duggan must contend with: his lack of political infrastructure and the voter turnout operation a party provides. The mayor can develop his own, but doing so requires immense resources and organization.

“I have people in 83 counties that are willing to knock doors, willing to be part of a field campaign, willing to actually spread the message of what Democrats are and what they’re fighting for,” Hertel said. “He doesn’t have that—has to build it from scratch.”

Duggan is trying to replicate what worked when he first ran for mayor in 2013.

He was a newly minted Detroiter, having moved into the city from the adjacent working-class suburb of Livonia to meet the candidate eligibility requirement. Encouraged to run by locals impressed with his corporate turnaround of the Detroit Medical Center hospital system, Duggan was largely unknown. So he asked voters all over Detroit to invite him to their homes for intimate meet-and-greets. The gatherings eventually attracted more voters than could fit in a living room and were moved to churches and restaurants.

He won, as a write-in, by 20 points.

Duggan was a relative unknown beyond southeastern Michigan when he launched his first campaign for statewide office last December.

To build name recognition, the mayor has been crisscrossing the state’s 83 counties, meeting with any group, of any size, that will have him—usually arriving in a silver 2018 Ford Taurus sedan (since discontinued) driven by his son and top political adviser, Ed Duggan. The younger Duggan, a former Whitmer aide, wasn’t a nepotism hire. He served as the Michigan political director for Democratic nominee Joe Biden (2020) and Michigan state director for nominee Kamala Harris (2024) and leads a threadbare staff that includes at least one Republican: communications adviser Andrea Bitely.

“I’m going from farms to small towns, to suburban communities, to cities all across the state and just as I did when I ran for mayor and I went house to house,” Duggan told a crowd of roughly 75, a mix of small business owners and local elected officials, intrigued enough to show up early in the morning at Waterside Social, a bar and grill on the banks of Lake Orion, in northern Oakland County, to kick the tires on his candidacy.

“I need to know—whoever comes in that governor’s position—that we’re able to work with them to get stuff done because stuff’s not getting done in Lansing,” Michigan Rep. Donni Steele, a Republican, told The Dispatch as Duggan’s event in Lake Orion began.

Does she believe the mayor can win? After all, Duggan’s campaign infrastructure is still minimal and per the most recent fundraising reporting period, the mayor spent $1 million, nearly all of the $1.2 million he collected, although he finished with a competitive $2.5 million in the bank and enjoys the support of the political nonprofit Put Progress First, a group allowed to accept nondisclosed donations in unlimited amounts.

“It’s going to be interesting to watch,” Steele said, hedging her bets. “If there was a time in history to change the dynamic, I think it’s now.” (Steele blames the Whitmer administration for Lansing dysfunction, plans to support the GOP nominee, and views James, who has twice run unsuccessfully for Senate, as the most electable Republican statewide.)

In two events The Dispatch covered, Duggan opened with brief remarks recounting his unlikely rise to Detroit mayor, as if to head off natural doubts about his prospects. Then, he enthusiastically invited attendees to discuss whatever was on their minds. In Lake Orion, the assembly of small business owners was curious about Duggan’s plans for shoring up Michigan’s shaky economy, plagued by a 5.2 percent unemployment rate that ranks 48th among all 50 states and Washington, D.C., according to figures issued by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics in September.

“The restaurant industry’s suffering, there’s been record closures—thousands of us out there that are struggling,” restaurateur Drew Ciora told Duggan, teeing up a question on changes to servers’ compensation under a minimum wage hike approved by state lawmakers that has taken a bite out of restaurants’ already slim profit margins, although less than might have happened thanks to a bipartisan compromise. Others focused on taxes.

Would Duggan support reforms allowing municipalities to keep more of the tax revenue they generate? The mayor didn’t say “no.” Would Duggan seek to eliminate the state income tax to make Michigan more competitive for jobs and corporate relocations with states like Florida, Tennessee, and Texas? Here he did say “no,” emphasizing: “You will find politicians who will come in and tell you exactly what you want to hear. How’s that worked out? … I’m going to tell you the truth.”

Indeed, candidates who run against the two major political parties, even those who wage that battle from within, typically position themselves as courageous truth-tellers while centering their pitch around leadership, an often amorphous quality that nonetheless carries a strong emotional pull for voters. Problem-solving is easy, they’re prone to claim. It’s finding a candidate with the political courage to embrace those readily available solutions that’s the real problem.

And so it is with Duggan, who is fond of telling a story about an economic innovation incubator in Detroit that keeps losing growing firms to Columbus, Ohio, because the neighboring state’s Republican governor, Mike DeWine, and its capital city’s Democratic mayor, Andrew Ginther, have partnered to create a superior public infrastructure and state regulatory environment for up-and-coming businesses.

“The good thing is: Who’d want to live in Columbus, Ohio, when you could live here, right?” Duggan told the audience in Lake Orion. “We have natural advantages. We don’t have a leadership advantage.”