Eight Things to Know About Big Philanthropy and the Populist Reaction Against It (full series)

Getting Bigger | More Liberal and Progressive

More Politicized | Renewed Public Scrutiny

2. Big Philanthropy has been getting more liberal and progressive, overwhelmingly so in the policy- and advocacy-oriented context.

Any categorization by ideology assumes the risk of subjectivity. Given this caveat, it is fair to observe that none of these top 25 private foundations could fairly be characterized as solidly conservative—certainly nowhere close to representing or even reflecting the ascendent populist conservatism that’s given rise to the current aggressive policy reaction against Big Philanthropy.

The Lilly Endowment, which some may think describable as conservative, actually now publicly considers its own philosophy as “conservatively progressive,” and its grantmaking portfolio seems increasingly to reflect the noun in that phrase. Similarly, while the Walton Family Foundation has historically substantially supported school choice and charter schools, its giving increasingly includes environmental protection and related advocacy. And as for John Arnold, he once tweeted, accurately, “I’ve now been called the next Koch brother by the far left press and the next George Soros by the far right. I’m an equal opportunity special interest pot stirrer.”

For conservative-foundation comparison, the Diana Davis Spenser Foundation is 112th on the Chronicle’s February 2025 list with $1.36 billion in assets, the Daniels Fund is 117th with $1.36 billion in assets, the Daniels Fund is 117th with $1.3 billion, the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation is 165th with $987.07 million in assets, the Charles Koch Foundation is 215th with $748.22 million, the Sarah Scaife Foundation is 272nd with $610.29 million, and the Smith Richardson Foundation is 309th with $546.2 million.

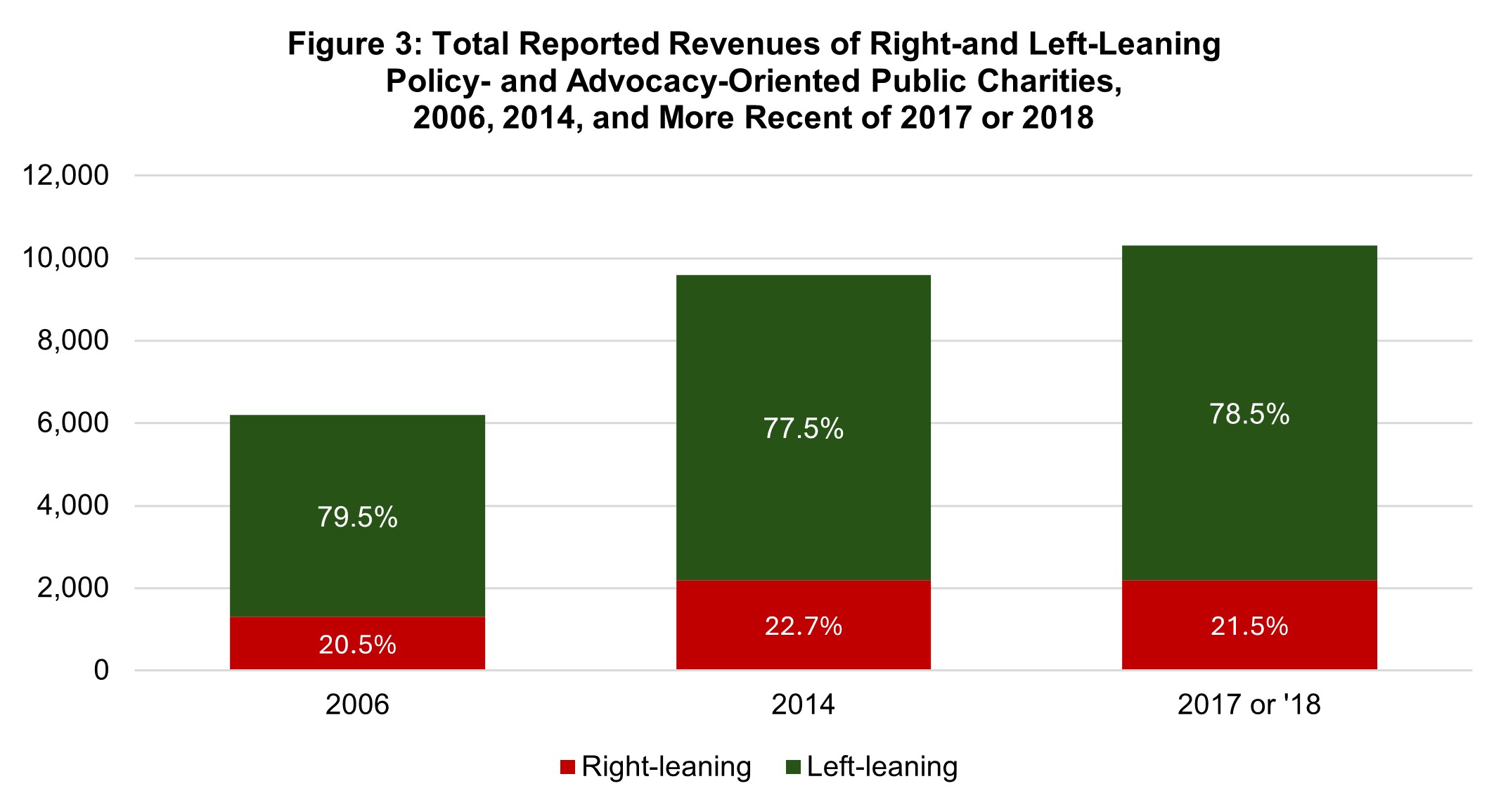

To make a meaningful further comparison of policy- and advocacy-oriented philanthropy in particular, my colleague Michael Watson and I found that in 2014 the reported revenues of 1,450 selected policy- and advocacy-oriented public charities totaled approximately $9.6 billion, up from about $6.2 billion in 2006, as reported in the Capital Research Center’s (CRC’s) 2018 The Flow of Funding to Conservative and Liberal Political Campaigns, Independent Groups, and Traditional Public Policy Organizations Before and After Citizens United.

The groups for this analysis were selected from the grant-recipient lists of 12 major private foundations, six of them right-leaning and six left-leaning. There were 372 right-leaning recipients and 1,078 left-leaning ones. The right-leaning groups’ revenues totaled just less than $2.2 billion in 2014, up 71 percent from $1.3 billion in 2006. But the left-leaning groups’ revenues totaled more than $7.4 billion in 2014, up 50 percent from $4.9 billion in 2006.

In 2020, Watson and Shane Devine revisited the question in a follow-up report for CRC, similarly comparing support of and right- and left-leaning public charities. According to what were then the more recently reported figures (from either 2017 or 2018), their study found that 298 selected right-leaning groups’ revenues totaled just more than $2.2 billion, roughly the same as the conservative total in 2014, and 906 left-leaning groups’ revenues totaled almost $8.1 billion, up 9.65 percent from 2014.

As shown in Figure 3, in 2006, right-leaning policy- and advocacy-oriented charities received 20.5 percent and liberal ones received 79.5 percent of donations. In subsequent years, this ratio remained relatively stable. In 2014, conservative policy groups received 22.7 percent and liberal ones received 77.3 percent of total policy-oriented donations, and in 2017 or 2018, conservative groups received 21.5 percent and liberal ones received 78.5 percent.

Policy-oriented philanthropy skews overwhelmingly to the Left.

Relatedly, it houses and funds a democratically unaccountable and monoculturally progressive managerial elite.

James Burnham criticized the “new class” in his 1941 book The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World, Daniel Bell spoke of the “knowledge class,” Theda Skocpol described the withdrawal of elites from cross-class organizations to those of a nonprofit overclass, and many others have observed what’s now generally called the “managerial elite.” All of their criticisms apply quite directly to those who are employed by and administer democratically unaccountable and monoculturally progressive Big Philanthropy. To those who’ve been paying attention, they’ve actually done so for quite a while, and increasingly.

“Overall, the shift of the center of gravity from local chapter-based member associations and church congregations to foundations, foundation-funded nonprofits, and universities represents a transfer of civic and cultural influence away from ordinary people upward to the managerial elite,” Michael Lind writes in his 2020 book The New Class War: Saving Democracy From the Managerial Elite.

Many of today’s so-called community organizations are not so much grass roots as AstroTurf (an artificial grass). A contemporary community activist is likely to be a university graduate and likely as well to be rich or supported by affluent overclass parents, because of the reliance of nonprofits on unpaid interns and staffers with low salaries. Success in the nonprofit sector frequently depends not on mobilizing ordinary citizens but on getting grants from the program officers of a small number of billionaire-endowed foundations in a few big cities, many of them named for old or new business tycoons, like Ford, Rockefeller, Gates, and Bloomberg. Such “community activists” have more in common with nineteenth-century missionaries sent out to save the “natives” from themselves than with members of local communities who headed local chapters of national volunteer federations in the past.

Earlier this year, in a contribution entitled “How Philanthropy Made and Unmade Liberalism” to Mastery and Drift: Professional-Class Liberalism Since the 1960s, Temple University history Professor Lila Corwin Berman tough-mindedly critiques what she calls professional-class liberalism’s “philanthropic governance.” “A bevy of anti-regulatory, pro-market, and state-shrinking measures endorsed across party lines from the 1970s through the 1990s smoothed the way for the rise of philanthropic governance,” by Berman’s anti-neoliberal assessment.

Together, they directed public funds and plaudits toward private foundations and other philanthropic bodies.

By the final decades of the twentieth century, the logic and structure of philanthropy had permeated every realm of American power, from domestic and foreign policies to corporate practices to grassroots politics. In other words, no domain of American power operated bereft of the capital and logic of philanthropy. This fact served to lash together disparate political actors from the left and the right, who no matter their policy divisions all conceded to—and often lauded—philanthropic governance.

To those who may perhaps be paying closer attention in the wake of the 2024 election, there have been healthily negative appraisals on both the left and right of the practical and political effects of “The Groups” of philanthropically funded entities that exercise an inordinate amount of influence over candidates and policymakers. The Groups, these analyses either imply or say, would do better to be more cognizant of and responsive to the wishes of common, non-overclass citizens who have few avenues to effectively express themselves other than electorally.

More recently, my Giving Review co-editor William A. Schambra notes that everyday’ers practice their own philanthropy very much differently than Big Philanthropy. Jason Lewis has complementarily noted that they are very much alienated from a distant Big Philanthropy that now clumsily and tardily seeks to enlist them in defense of its activities against populist policy proposals to rein in its power and prestige and cut back on some of its privileges and prerogatives.

In the next installment, Big Philanthropy has been getting more politicized and partisan.