Authored by T.J. Muscaro via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

For the first time in more than 50 years, NASA has mounted a rocket on the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center in preparation for a manned flight around the moon.

The super heavy lift rocket is called the Space Launch System. Fueled by more than 700,000 gallons of liquid oxygen and hydrogen and two solid rocket boosters reminiscent of the space shuttle era, the orange and white behemoth could, as soon as Feb. 6, carry the Artemis II crew—NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen—on their 10-day voyage around the moon and farther from Earth than any astronauts have gone before.

Hundreds of men and women who had a hand in assembling the rocket braved the winter cold on Jan. 17 to watch the ship roll out of the vehicle assembly building and move to the launch complex. The Artemis II crew, mission leaders, and NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman were also on hand to commemorate the milestone.

But there is still a lot to be done before liftoff, and the exact launch date is still to be determined.

Here is what to know about the Artemis II mission, as well as what preparations and parameters still stand in the way of launch.

What Is Artemis II?

Artemis II is the second mission of NASA’s Artemis campaign. Named after the ancient Greek goddess of the moon and Apollo’s twin sister, the program’s purpose is not only to return manned missions to the moon, but also to establish a sustainable, permanent human presence on the lunar surface and in lunar orbit before 2030.

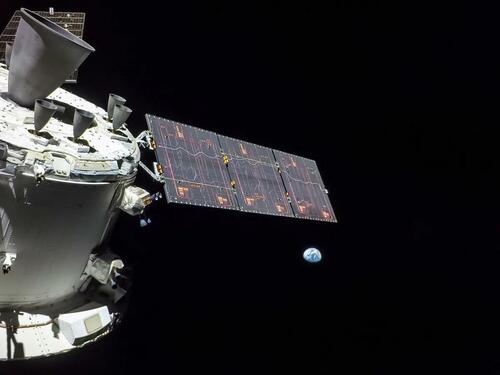

Lead flight director Jeff Radigan emphasized that the mission is first and foremost a test flight. Wiseman, Glover, Koch, and Hansen will be the first to fly aboard the Space Launch System and NASA’s Orion spacecraft, which includes the crew capsule and a service module provided by the European Space Agency.

NASA’s priorities for the test flight include successfully demonstrating that the spacecraft and ground teams can sustain the crew members for the entirety of the mission and return them safely to Earth, successfully demonstrating the operations and procedures that are essential for future crewed moon missions, and demonstrating emergency systems and operations.

These demonstrations will include proving the readiness of critical functions, including life support systems, radiation shielding, and maneuverability for docking on future missions, as well as solidifying everyday procedures onboard. That includes how to optimally stow flight suits and fulfill physical exercise requirements in the cramped quarters of the crew capsule.

The crew will also test a new laser communication array, participate in ship-to-ship communication with the International Space Station, and conduct human science experiments. Those experiments will not only broaden understanding of how deep space affects the body, but also improve NASA’s ability to customize treatments for each astronaut.

“This is a test flight, and there’s things that are going to be unexpected,” Radigan stressed at a news conference on Jan. 16. ”You know, I think we’ve prepared for those as much as we can, and we’re very much looking forward to flying this mission successfully with the crew and learning what we need to on Artemis II moving forward and paving the road for future Artemis missions.”

Artemis II Launch

Artemis II could launch as early as Feb. 6 or as late as April 6. That is, if the space agency wants to keep its long-held promise that the mission will launch before the end of April.

Because of parameters set by mission objectives and vehicle limitations, NASA has isolated six-day launch windows at the start of each month.

The first group of launch opportunities will be Feb. 6, Feb. 7, Feb. 8, Feb. 10, and Feb. 11. After that, NASA will have launch opportunities on March 6, March 7, March 8, March 9, and March 11, and then, if necessary, launch opportunities on April 1, April 3, April 4, April 5, and April 6.

Limiting factors include the need for the position and rotation of the Earth and the moon to be aligned properly on launch day so the Space Launch System can lift the spacecraft into the correct high-Earth orbit. The spacecraft can then set off on its “free-return trajectory” around the moon, ending with a shortened re-entry path toward a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

All the while, because of the service module’s solar panel wings that provide power, the spacecraft and its service module cannot be in darkness for more than 90 minutes.

On top of these conditions, the moon rocket still needs to undergo some testing and systems integration before it is cleared for launch, including a “wet dress rehearsal.” That is a practice in which ground operations will put the rocket through launch day conditions such as fully loading and unloading the rocket with fuel, powering up and powering down critical systems, and practicing closeout procedures that would secure the crew in the capsule.

If the wet dress rehearsal exposes a problem such as a fuel leak, as was the case during Artemis I, that must be addressed before proceeding further.

The weather could also cause delays. For example, if the temperature at the launch pad falls below a defined temperature constraint—from 38 degrees Fahrenheit to 49 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on wind and relative humidity—for 30 minutes, the moon mission will not be able to get off the ground. And if lightning or thunderstorms are detected within 10 nautical miles of the launch pad, the launch could be delayed or scrubbed.

Although NASA only published its launch windows for the next three months, Artemis Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson said a suitable launch window exists for every month this year, and the rocket can remain on the pad exposed to the elements for two launch windows before it would need to be rolled back into the Vehicle Assembly Building.

Artemis II Flight Plan

Whenever it does launch, NASA leadership expects Artemis II’s 10-day flight to begin with a night launch and end with a nighttime splashdown.

The first two days of the mission have been described by the crew and flight directors as grueling in terms of workload.

Day one will kick off with a more-than-three-hour journey from Launch Complex 39B at Kennedy Space Center to a high-Earth orbit, flying as high as 46,000 miles. By comparison, the International Space Station generally flies at an altitude of 250 miles beyond Earth.

Once in high-Earth orbit, Wiseman, Glover, Koch, and Hansen will conduct a roughly 23-hour checkout of the spacecraft while still relatively close to the Earth. That checkout includes what NASA calls a “proximity operations demonstration.” Glover will take manual control of the spacecraft to test the maneuverability of the Orion spacecraft as it relates to docking. Using the detached upper stage of the Space Launch System as a point of reference, he will fly as close as 30 feet to the stage. After all, the Orion spacecraft will have to be able to dock with a lunar lander built by either SpaceX or Blue Origin in order for its future crews to land on the moon.

This demonstration will make Glover the first astronaut to manually fly NASA’s new moon-bound spacecraft, putting him in league with the Apollo astronauts who came before him.

Mission leaders said the astronauts will get a rest period of approximately four hours during the first day before waking up to conduct one more orbital adjustment ahead of their trans-lunar injection.

If all checkouts and tests reveal a healthy spacecraft, Artemis II will perform its “translunar injection burn” just 25 hours and 37 minutes into the mission, when its crew fires the spacecraft’s main engine to set it off on a course from the Earth to the moon on a free return trajectory.

It will take the spacecraft and her crew three days to reach the moon. During those proverbial days at sea, the crew members will perform three trajectory correction burns, test communications on the deep space network, and demonstrate operations inside the brand-new spacecraft, including rapidly putting on their spacesuits. They will also review imaging plans for the lunar flyby in anticipation of the geological observations that await them.

The spacecraft will enter the moon’s gravity four days and seven hours after launch, and roughly 15 hours later, Artemis II is expected to pass the farthest point from Earth reached by any manned Apollo mission.

It is in this newly-reached frontier of deep space that the crew members will make their closest approach to the moon and perform their flyby, roughly five days after liftoff. They will have three hours to observe the far side of the moon.

Mission leaders said the moon will appear to the crew members to be the size of a basketball held at arm’s length as they pass at a distance of 4,000 to 6,000 miles above the lunar surface. The crew will be tasked with performing geological observations by a lunar science ground team, which will be following along and passing requests to the astronauts from Houston in real time, save for a brief loss of signal when the moon is directly between the crew and the Earth.

Erroneously called “the dark side of the moon” because it is in darkness while the side seen from Earth is lit, the moon’s far side is expected to be lit by sunlight, possibly to a greater extent than on any Apollo mission. If so, Artemis II’s flyby could reveal parts of the moon never seen by human eyes.

However, NASA will not know for sure how much of the far side will be in sunlight until the crew is on its way, and mission science leaders have confirmed that far-side visibility has no effect on the launch date.

It will take another three days to get back home. The crew will make more trajectory corrections, participate in a lunar science debrief, and conduct a demonstration of radiation shielding, as well as another manual flight demonstration.

Read the rest here…

Loading recommendations…