Introduction

During April 8–11, 2024, [1] and January 24–30, 2025, [2] the Manhattan Institute polled representative samples of the likely 2025 mayoral electorate in New York City to gauge registered voters’ opinions on electoral reform. Looking at the consistencies and changes between the 2024 poll and the 2025 poll, we can draw inferences about the durable beliefs of NYC voters and about short-term changes in voters’ perceptions.

Our results indicate sizable discontent with the current electoral system, including “fully closed” partisan primaries, in which only registered members of a political party may vote in the party’s primary, which inhibits voter participation and limits political competition.

Smart Policy, Straight to You

Don’t miss the newsletters from MI and City Journal

Respondents’ support for reforms such as open primaries and nonpartisan primaries indicates a broad desire among New Yorkers for a more inclusive and competitive electoral process. Reform would counteract the existing problem of limited electoral competition, aiming to enhance voter participation and recalibrate the political dynamic in a city where electoral competition takes place largely within a single party’s primary.

On December 12, 2024, Mayor Eric Adams announced the formation of the Charter Revision Commission, tasked with recommending changes to the New York City Charter, commonly known as the city’s “constitution.” Past commissions have sought to reform NYC’s electoral system, and the current commission, though tasked initially with focusing on housing, has expanded its purview to include electoral reform.[3] The Charter Revision Commission’s preliminary report contains several options for reform, including changing the structure of city primaries and moving local elections to even-numbered years.[4] Come November, city voters may be asked to approve electoral reform proposals.

The results of MI’s polls underscore voters’ desire for changes in the way that the city conducts elections, particularly reforms that incorporate nonpartisan primaries for the mayoral election.

A Brief Background on New York City’s Electoral Dynamics

New York City has one of the most restrictive electoral systems in the United States. Its fully closed partisan primaries, four-month party registration deadline,[5] and vastly lopsided voter registration limit political competition.[6] Even after voters adopted ranked-choice voting (RCV) for local primary and special elections in 2019, the electoral dynamics in the city have remained largely the same. One political party, the Democratic Party, enjoys supermajority control of the city council and the three major citywide offices of mayor, comptroller, and public advocate.

Closed partisan primaries have skewed the city’s electoral dynamics. One million registered city voters do not affiliate with any political party, so they cannot vote in any primary.[7] Neither can those affiliated with nonmajor parties that do not hold primaries. Republicans sometimes do not hold a primary, even for mayor. About 66% of all city voters are registered as Democrats; so for practical purposes, the only local election that matters is the Democratic primary, where the winner usually goes on to an easy general-election win.

Closed primaries dampen voter participation in many other ways. Holding the primary in June requires voters to sacrifice time and effort to vote, discouraging turnout. Even during a highly publicized race for mayor in 2021, in which there was no incumbent candidate, only 26.5% of eligible voters participated in the mayoral primary.[8] Because most general elections are uncompetitive, voters often don’t bother to turn out in November, either. Approximately 23.3% of registered city voters voted in the November 2021 general election.[9] Many general-election races for city council do not sport a Republican or third-party challenger.

Consequently, political competition tends to manifest between factions within the Democratic Party. Far from being a monolith, the Democratic Party comprises various blocs, including the Democratic Socialists of America-aligned left, public-sector union-backed candidates, and those who rise from the county political machines. Particularly in down-ballot races, voters often lack information about these factional and intra-party political dynamics when deciding which candidate best aligns with their preferences and values. Voters who participate in the primary do not find cues on the ballot that could signify which candidate is closest to their values and preferences.

The importance of the Democratic Party primary incentivizes voters to register with the party, even if it does not reflect their true views and preferences. This creates yet another factional dynamic within the Democratic Party, albeit one that is less visible. Previous research has not explored how many people are registered as Democrats mainly so that they can have a say in the primary.

Furthermore, New York has one of the most restrictive party enrollment deadlines in the United States.[10] In 2025, voters had until February 14 to change their enrollment, 132 days before the June 25 primaries.[11] By contrast, other closed primary states have far more permissive deadlines for party enrollment. Florida allows for changes up to 29 days before the primary election,[12] and Pennsylvania allows changes 15 days before.[13]

Complicating the picture further is that voters generally understand the values and policies of the Democratic and Republican Parties through the lens of national-level politics. As Christopher Elmendorf and David Schleicher observed, voter registration laws unify parties across subnational and national levels of government—it’s not possible to register as a local Republican and federal Democrat, for example.[14] Many New Yorkers find the national Republican political brand unpalatable and unsupportable, even if they may prefer traditional Republican priorities like greater fiscal discipline and police-based public safety. Donald Trump’s stripping of federal funding for New York and cutting of the federal workforce, both unpopular in New York, have likely amplified this effect.[15]

NYC’s local political environment is also heavily influenced by special interests, especially public-sector unions, real-estate developers, and tenants’ advocates. To compete effectively in city politics, candidates must curry favor among these groups, not necessarily align their platforms to the preferences of the median voter. These groups have the funding and support base sufficient to win low-turnout primary elections.[16] If city officials threaten these groups’ interests, they risk a group-backed primary challenger in the next election.

In 2003, then-Mayor Bloomberg appointed a charter revision commission to replace closed primaries with nonpartisan elections.[17] Bloomberg, who won his first two terms as a Republican, believed that nonpartisan primary elections would broaden political opportunity and reduce the influence of Democratic insiders.[18] This effort, which would also have removed party labels from ballots, failed at the ballot box—largely because the Democratic Party and labor unions opposed it.[19]

While the city’s electoral problems have been well-known for decades, the voting public’s attitudes about many of these issues are much less certain. Voter registration totals over the past several years have revealed that more New Yorkers have opted to register without affiliating with a party, despite the penalty of not being able to participate in primaries.[20] Local unaffiliated voters generally resent this penalty, and up to two-thirds would vote in local races for mayor or city council if they could.[21] The literature on voter preferences also consistently shows that a majority of Americans wish to have a third-party option.[22]

In their survey of 3,000 U.S. adults, Boatright, Tolbert, and Micatka reveal that most Americans wish to reform primary elections, and particularly through open primaries.[23] Their results show:

[A] large majority of Americans express support for many reforms when the reforms are described to them (including details about the benefits). They are particularly supportive of reforms that appear to increase citizen choice (i.e., to be broadly democratic), and they are more skeptical of reforms that would restrict choice or enhance the role of parties as gatekeepers.[24]

Large percentages of respondents, however—generally a fourth to a third—did not know enough about various primary reform proposals to respond.[25] Those with greater political information or higher levels of education, moreover, were less likely to favor reform. Strong Democrats, a highly represented group in NYC, were twice as likely as pure independents to approve of the status quo.[26]

MI’s polling, among other things, sought to explore what share of registered NYC voters favor electoral reform. Because of the closed primary system’s incentives to register as a Democrat to have a say in what is often the only election that matters, before MI conducted its poll, it was reasonable to assume that at least 10% of Democrats “strategically register” for this reason. This subgroup likely has higher levels of dissatisfaction with their registered party and increases the party’s overall share of support for electoral reform.

Given the advantages that the closed-primary system offers city Democrats, however, it is also reasonable to believe that rational Democratic voters would seek to perpetuate these advantages by opposing electoral reforms. As a whole, then, we hypothesize that Democrats would likely be less supportive of primary reforms than unaffiliated, third-party, and Republican voters.

Results

Party Satisfaction

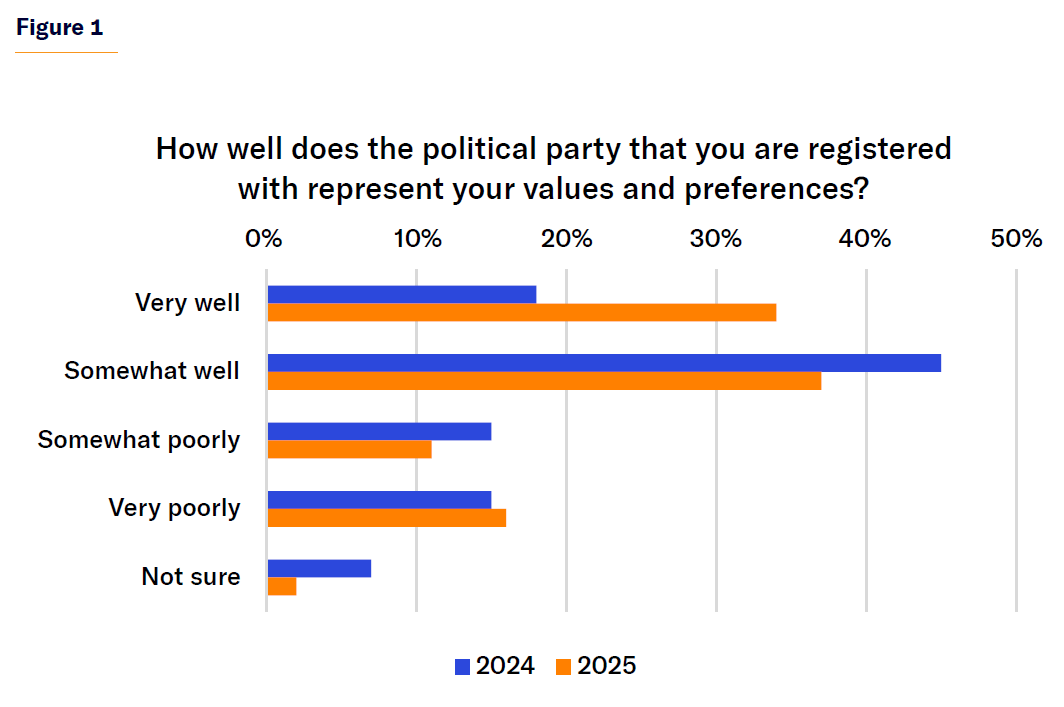

When asked in 2024 whether the political party they are registered with represents their values and preferences (Figure 1), only 18% of respondents said that the party does so “very well,” compared with 45% that responded, “somewhat well.” In the 2025 poll, however, 34% of voters agreed that the party with which they identified represented them very well, nearly double the previous year’s results, with 37% reporting “somewhat well.”

This pattern holds across political parties. Republicans in 2024, at 27%, were the most likely to say that the party represented them “very well.” This year, at 41%, Republicans remained the party with the highest proportion of respondents saying “very well,” and the only one with a plurality of those responses.

Among Democrats, 34% reported “very well” in 2025, double the 17% figure from the year prior; 48% said that the party represented them “somewhat well” in 2024. With 37% saying so today, their voters have solidified their party identity. It remains true, however, that a plurality of Democrats continue to view the party as representing them only “somewhat well.”

Reason for Democratic Registration

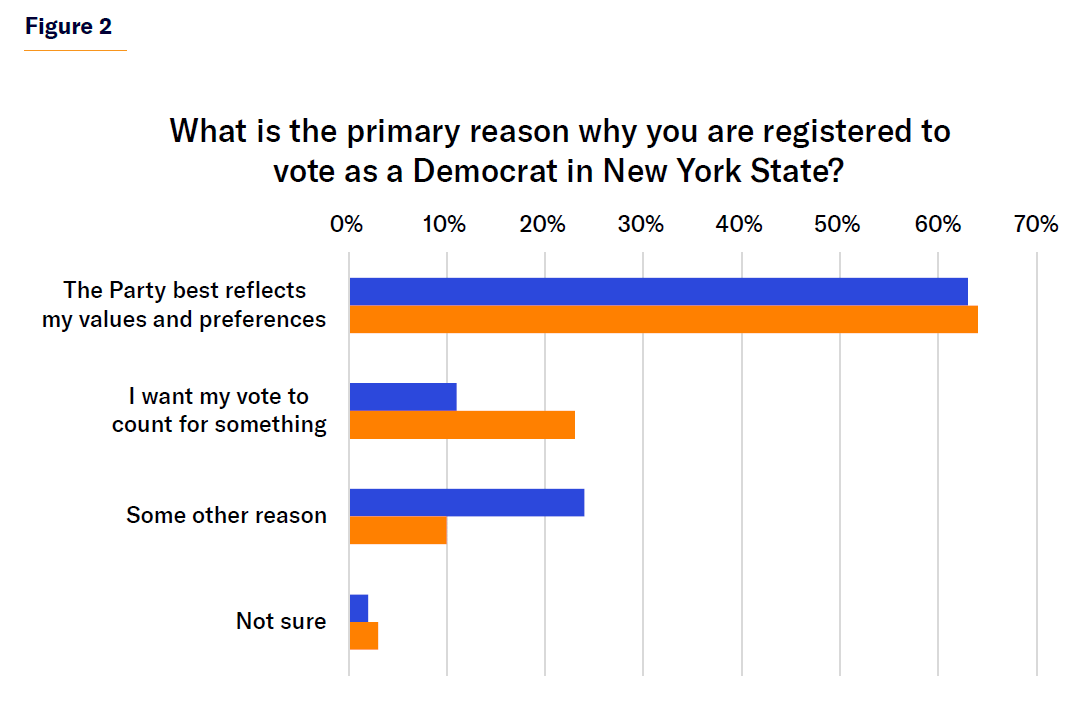

When registered Democrats were asked in 2025 why they were registered as they are, a large majority (64%) responded that it was because the party “best reflects my values and preferences.” This figure is nearly identical to last year’s 63% (Figure 2).

In 2024, 11% responded that it was “because in New York, the Democratic candidate almost always wins the general election, and I want my vote to count for something.” In 2025, however, 23% declared that they vote Democratic for that reason, more than double the year prior. Some 24% selected “some other reason” for registering as Democrats in 2024, while just 10% said the same in 2025.

Primary Reform

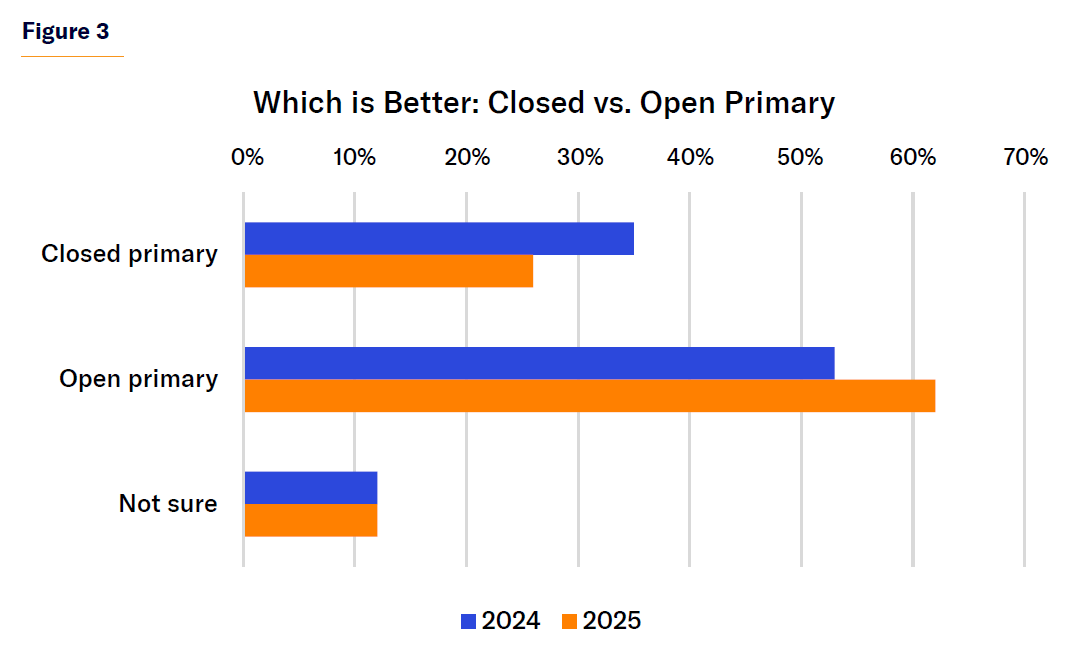

Our 2025 results indicate that when given a choice between an open and a closed primary (Figure 3), a strong majority (62%) believed open primaries to be preferable to closed. This is a nearly 10-point increase in support year-over-year (53% in 2024). Closed primaries received 26% support, and 12% were unsure.

Some who support closed primaries in the 2025 results believed that open primaries encourage more people to vote, as 70% of respondents believe that open primaries encourage more turnout (vs. 62% in 2024), compared with only 15% who believe the same about closed primaries and 15% who were unsure (Figure 4).

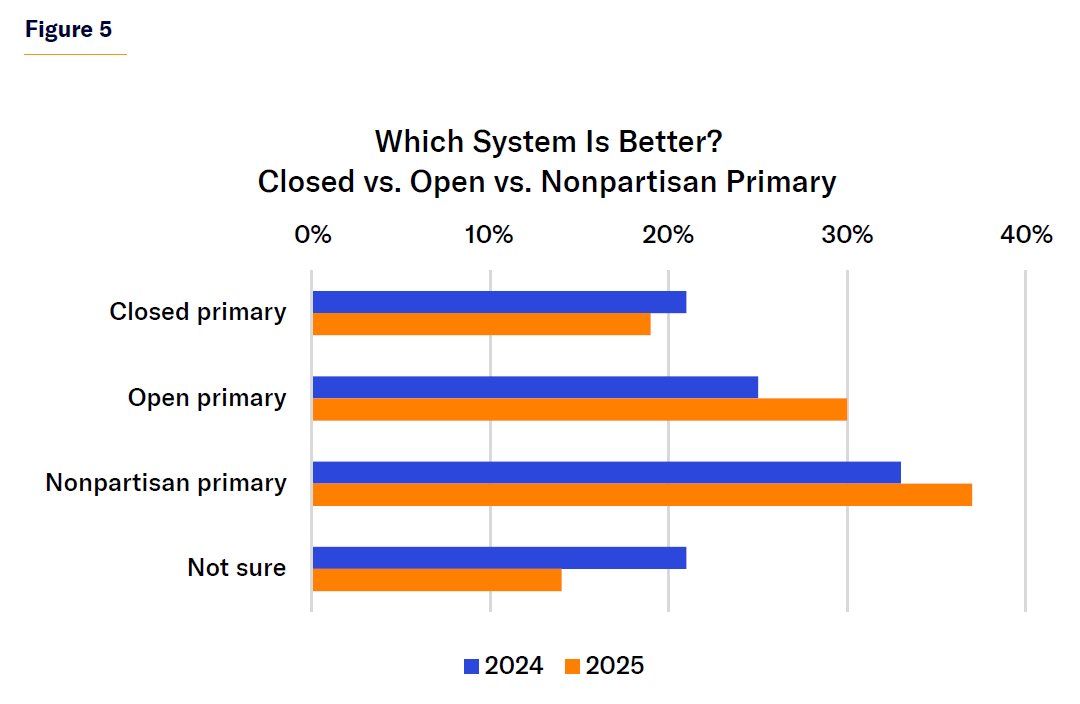

Respondents also received a prompt that introduced a nonpartisan primary (sometimes called a “top-two” primary used in some states, including California and Washington), in which all candidates, regardless of party, appear in a preliminary election open to all registered voters, who select the final candidates. After this prompt (Figure 5), a plurality of respondents in 2025 (37%) preferred this system over the 30% who preferred an open primary and the 19% who preferred a closed primary. In this case, voters indicated a growing inclination to alternative electoral systems. In 2024, 33% favored a nonpartisan primary, 25% an open one, and 21% a closed primary. Thus, the relative support mostly stayed the same, but closed primaries lost support, and nonpartisan primaries grew their plurality of support.

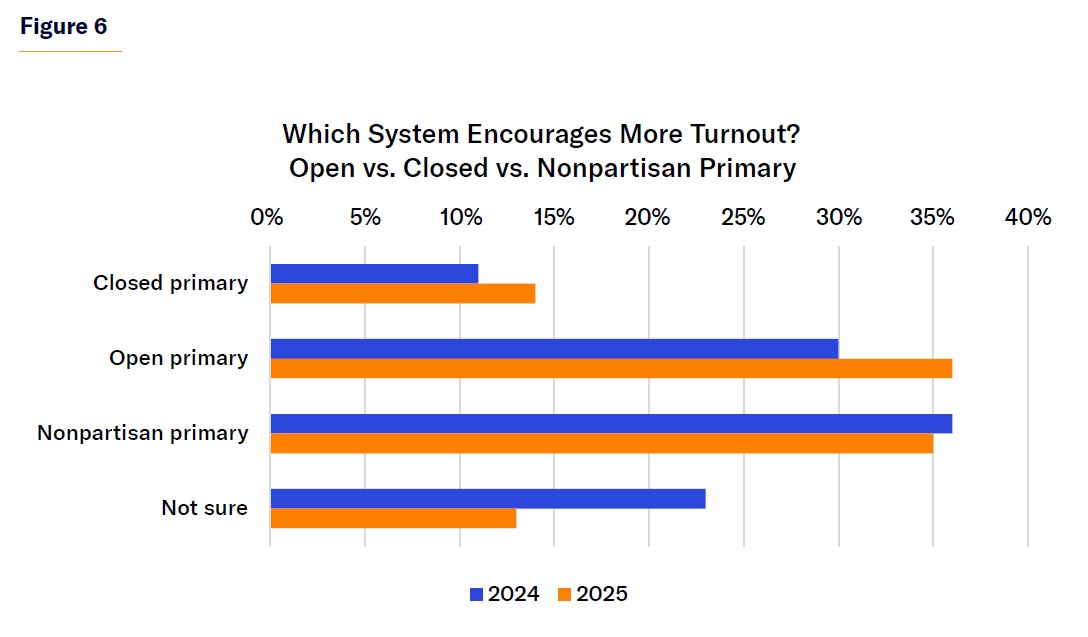

As Figure 6 illustrates, respondents believe that open primaries (36%) and nonpartisan primaries (35%) are the electoral systems most likely to encourage voter turnout.

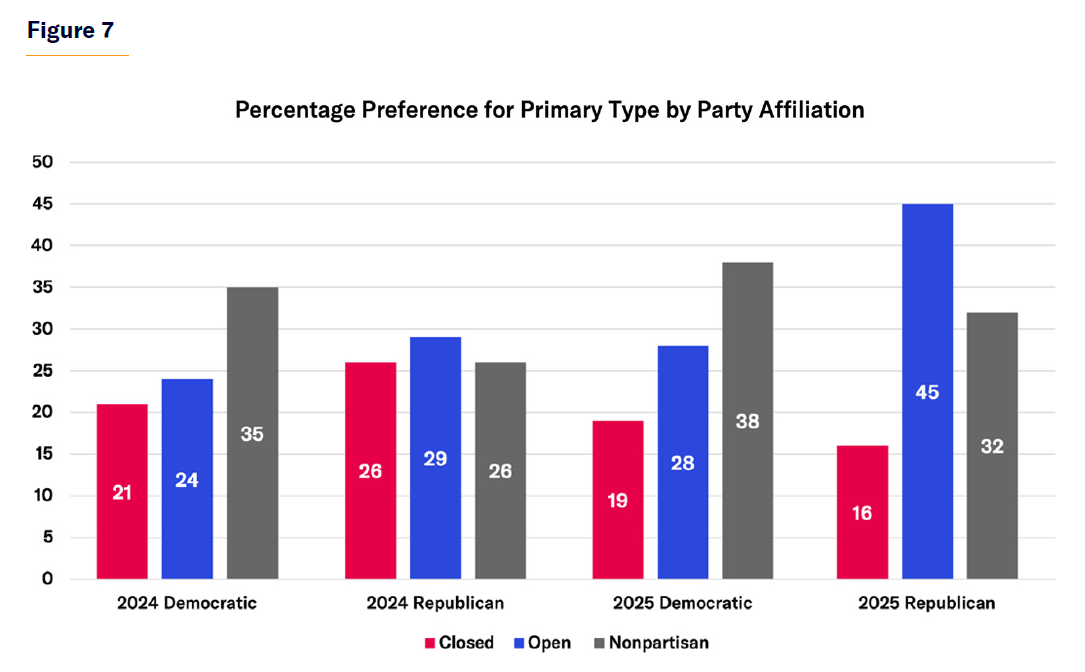

Figure 7 reveals that respondents registered as Democrats were more favorable to nonpartisan primaries (38% in 2025; 35% in 2024). Similarly, 28% of 2025 Democrats wanted to move to open primaries, a slight increase from 24% in 2024.

Among Republicans in 2025, 32% supported nonpartisan primaries and 45% wished to go to open primaries. That represents a much higher percentage than last year, when 26% supported nonpartisan primaries and 29% open primaries. As a general matter, Republicans appear somewhat more disposed to supporting open primaries, while Democrats favor nonpartisan primaries. Voters from both parties in 2025, however, prefer nonpartisan primaries to closed primaries.

Not Worth Voting in General Elections

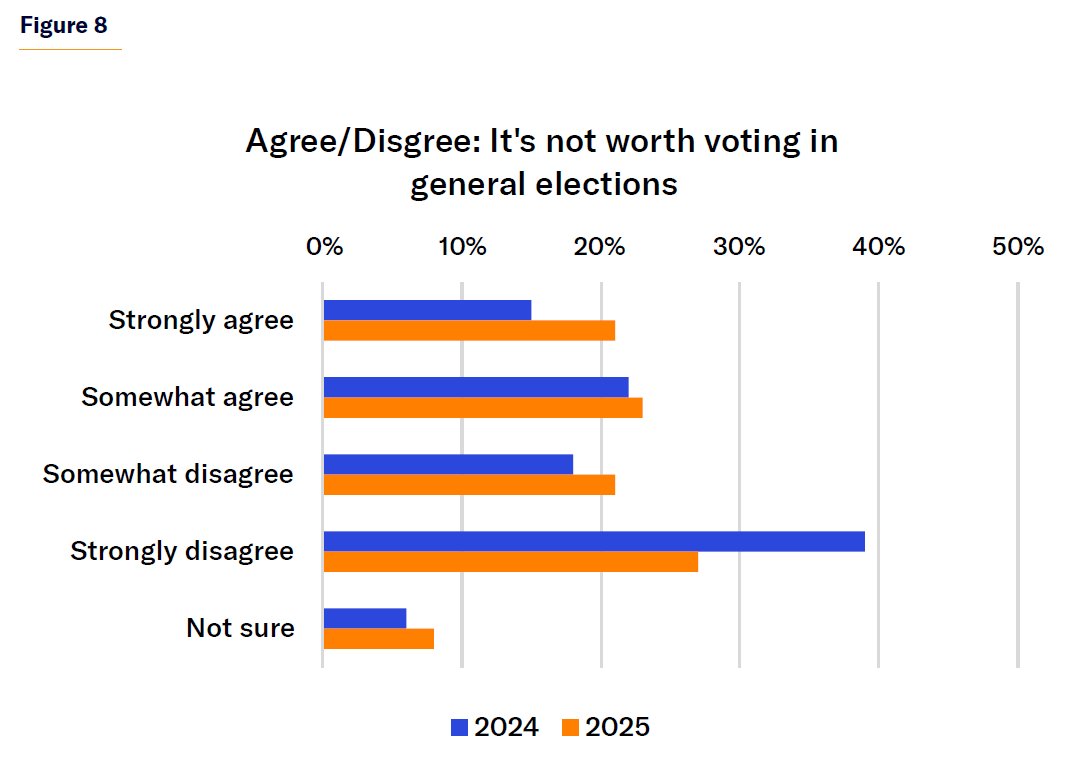

To gauge voters’ perceptions of whether the closed primary system has discouraged them from voting in the general election, we asked whether respondents agreed with the following statement: “New York City elections are usually dominated by the winner of the Democratic Party primary, so it’s not worth voting in general elections.”

Roughly two-fifths of voters agreed with that sentiment (Figure 8). In 2024, 15% and 22% answered “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree,” respectively. In 2025, those percentages increased to 21% and 23%. This indicates that a large swath of the electorate—well over a third—believe that the closed primary system makes voting in the general election largely moot. Among those who disagree with the statement, 39% and 18% “strongly” and “somewhat” disagreed, respectively, in 2024. In 2025, those figures changed to 27% and 21%.

Republicans (52%) are more likely to support the statement than Democrats (43%) and far less likely to strongly disagree (11% vs. 29%).

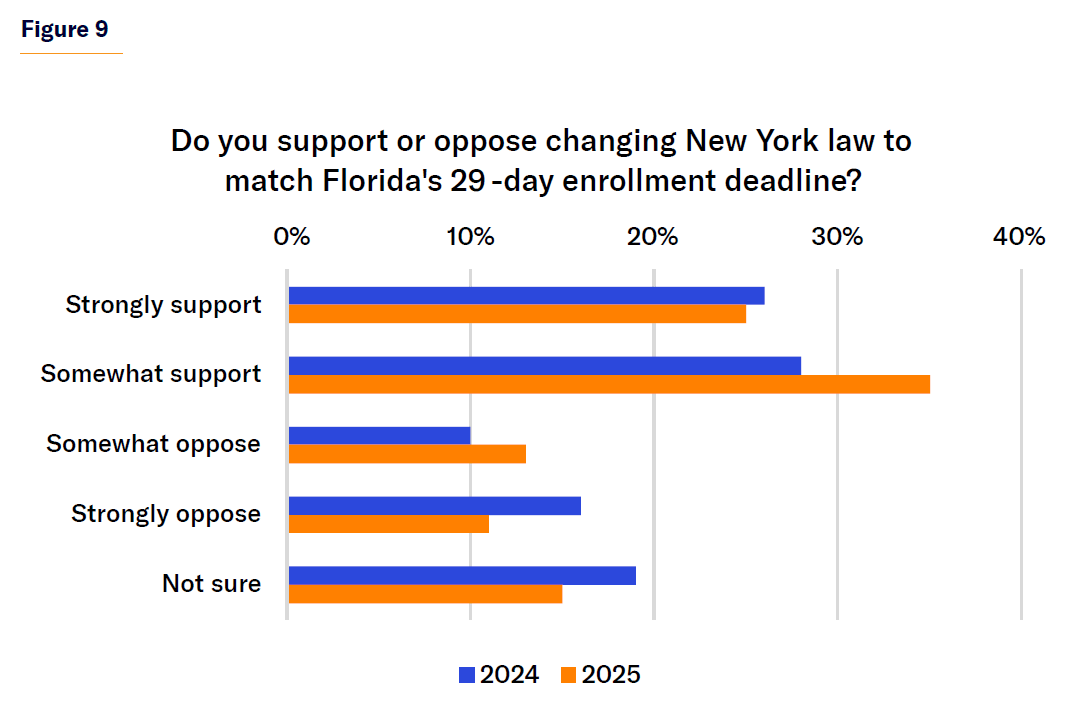

Closed-Primary Enrollment Deadline

As for postponing the deadline to enroll in a different party before New York’s closed primaries, a 60% majority of 2025 respondents favor moving to Florida’s 29-day deadline (25% strongly, 35% somewhat). Only 24% oppose this measure, with 15% not sure (Figure 9). This represents a six-point increase in support since last year (54%), with much of that drawn from those previously unsure. Majorities of Republicans, Democrats, and Independents likewise support this change. Republicans are the most likely to support the change, with 72% in favor to 13% opposed, and their support has increased more than 10 points from last year (59%).

Ranked-Choice Voting

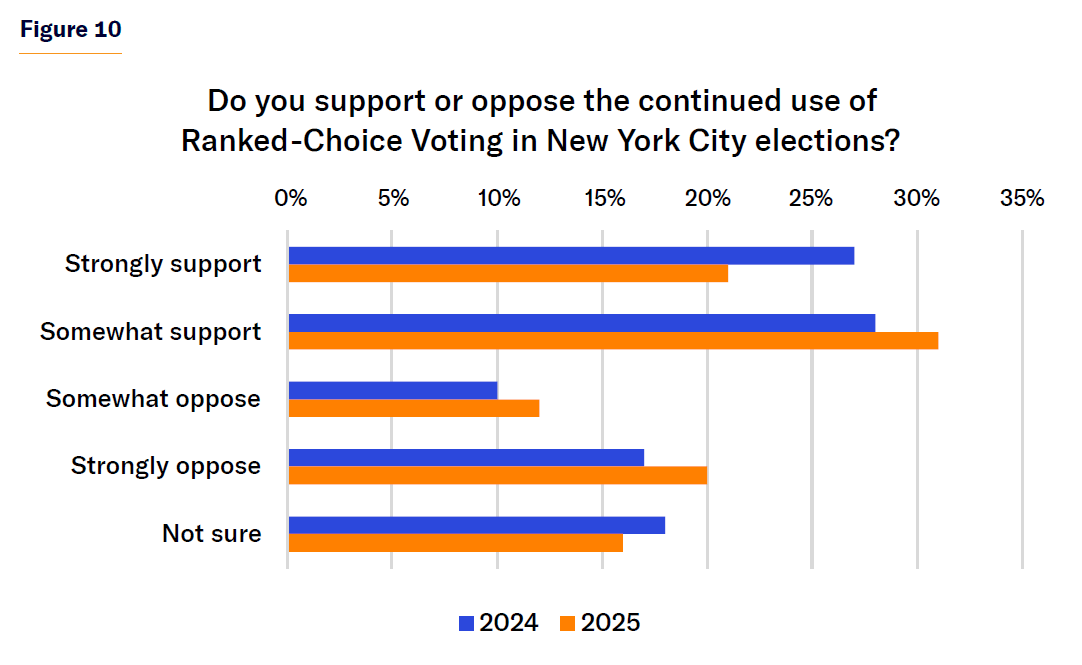

Since 2019, NYC has used RCV for two primary elections: the 2021 election cycle that included a mayoral race and the 2023 city council elections that resulted from the latest redistricting cycle. Given these two election cycles, we wished to gauge voters’ preferences about retaining RCV, particularly as the 2025 Charter Revision Commission considers electoral reforms (Figure 10).

Among all likely 2025 voters, 52% support the continued use of RCV in elections, with 32% opposed. This represents a slight decline in support from last year, when 55% supported the continued use of RCV, with 27% opposed, and 18% not sure. The biggest decline came from those who “strongly support” the system, while those who “somewhat support” gained slightly.

Even-Year Local Elections

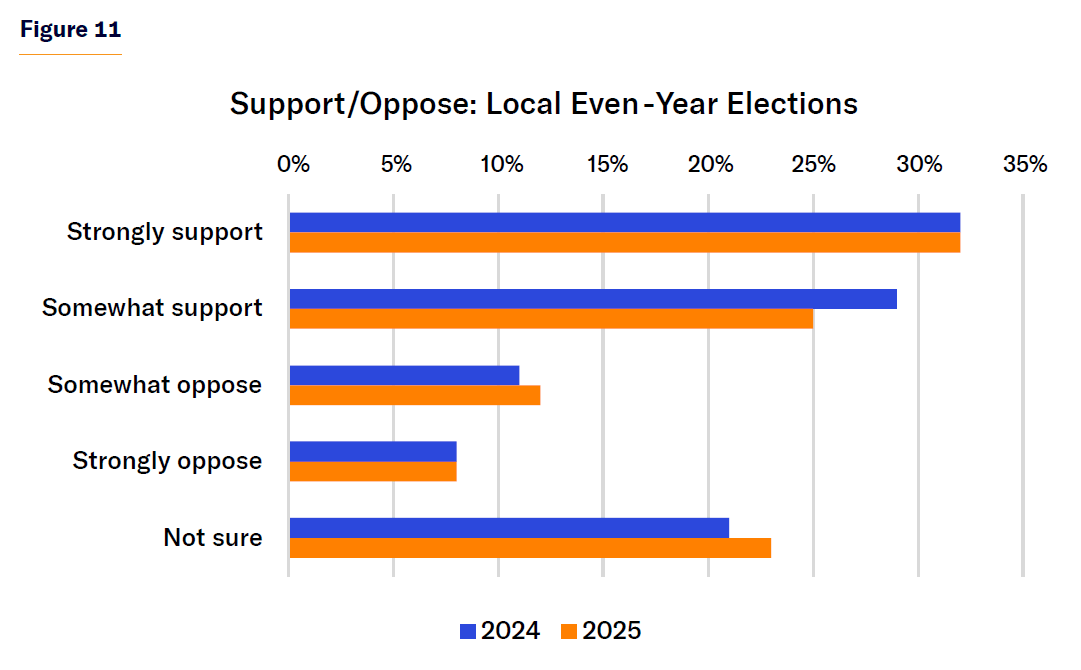

Among the reforms proposed to respondents, one that enjoyed broad support was moving the timing of local elections to coincide with federal elections for president or Congress, which fall on even-numbered years. This reform is frequently known as moving to “on-cycle” elections (Figure 11).[27] A full 57% of likely voters were in favor of this reform in 2025, with broad agreement among New Yorkers from all regions of the city, all age groups, ethnicities, education levels, and political affiliations. This is down slightly from last year’s poll, when 61% of likely voters were in favor of on-cycling, but nevertheless maintains a whopping nearly 40-point net favorability.

On-Ballot Endorsements

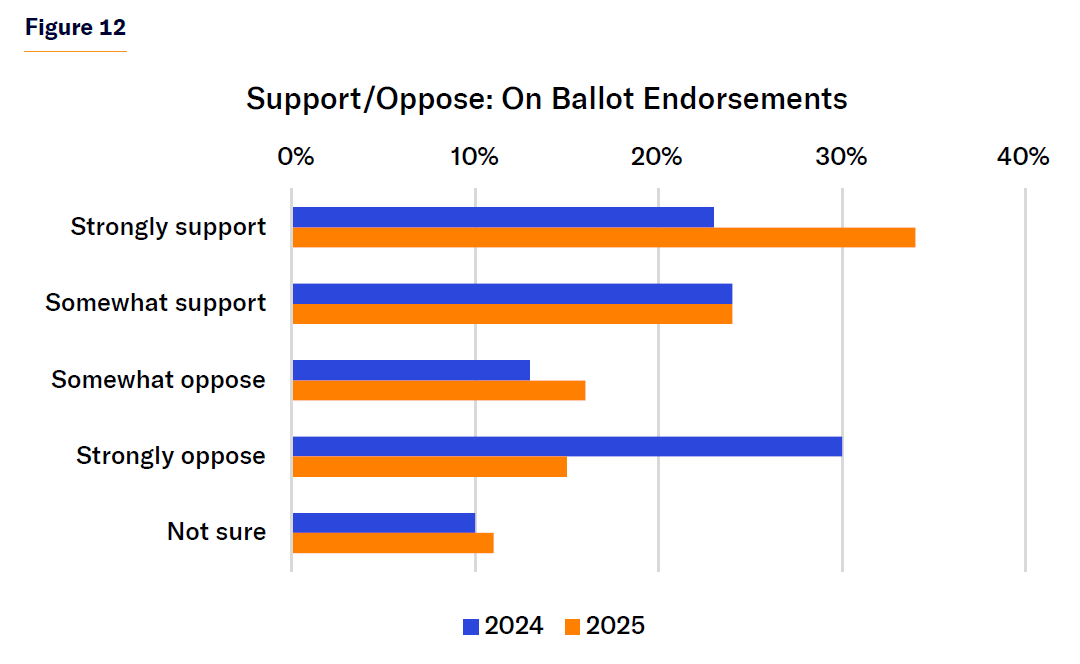

Respondents were also generally in favor of an experimental reform to provide information to voters on ballots in the form of printed endorsements from political leaders and organizations like newspapers and civic organizations.[28] A healthy majority of likely voters (58%) supported this reform. Last year, support stood at 47%. This year, only 31% opposed, compared with 43% in 2024 (Figure 12).

The reform was popular across age groups in 2025, but was particularly popular with the 35–49 group, with 70% support. Hispanics were the most supportive ethnic group by a wide margin, with 66% in favor. Majorities of college and noncollege respondents favored the display of ballot-endorsement information. Republicans (59%) and Democrats (58%) were both more in favor this year than last, when just under half of respondents from each party supported the reform.

Analysis

Our polling results suggest that a large and growing share of New Yorkers across political affiliations are frustrated by the electoral status quo. About 44% of voters in 2025 feel that it isn’t worth voting in the general election, given their usually uncompetitive nature—a sizable increase over the 37% who felt as such in 2024. It seems plausible that, in line with our hypothesis, many potential voters are not turning out on Election Day because they consider the conclusion foregone after the Democratic primary. Voters consistently believe that closed primaries are not as effective as open and nonpartisan primaries in facilitating turnout.

Interestingly, a much larger share of Republicans (36%) strongly agreed with that foregone-conclusion sentiment in 2024 than in 2025 (23%). Conversely, a larger share of Democrats in 2024 (46%) strongly disagreed with the sentiment than in 2025 (29%). This may suggest that Republican voters feel more frustration about the mostly foregone nature of the general election during presidential election years relative to local election years.

Also notable is the share of registered Democrats who responded that they were registered as such only in order to participate in the Democratic Party primary. Considering the closed nature of Democratic primaries in NYC, we hypothesized that at least 10% of Democrats are registered with the party in order to have their vote count for something. This hypothesis was confirmed: 23% of 2025 Democratic respondents selected this as the main reason for their party affiliation. In fact, the number of respondents indicating thusly has more than doubled since last year (11% in 2024), indicating growing dissatisfaction with the closed primary system and the factional tensions that exist within the local Democratic Party.

Our results largely corroborate those found by Boatright, Tolbert, and Micatka. A sizable share of NYC voters, up to a slim majority, want greater access and representation in the city’s political process. Voters’ preference for open and nonpartisan primaries over closed primaries likely indicates a desire to take local elections out of the factionalism dominated by the Democratic Party and alleviate the lack of electoral competition in general elections.

Moreover, the support for nonpartisan primaries and RCV suggests an appetite for an electoral framework that could foster broader candidate selection and open the process to all registered voters. That such a large share of 2025 Democratic voters (66%) supported open and nonpartisan primaries—although less than the Republican share (77%)—is somewhat surprising, as closed primaries give Democrats a general-election advantage.

We hypothesized that Democrats would be more likely to oppose primary reform, given the advantages that the current system provides to the local Democratic Party. Our results suggest that most local Democrats don’t consider these advantages when considering questions of electoral reform. Many likely consider the proposed reform in relation to how they vote as individuals, not the prospective effects a reform would have on their party.

This may also be because many local Democrats recognize, some perhaps implicitly, that the city’s electoral composition limits political competition mostly between the left and the center. Opening up competition via nonpartisan elections could allow for more candidates running on unique local issues and those with unorthodox or innovative policy positions.

Democrats’ openness to nonpartisan primaries is also likely partly attributable to the 23% who registered in order to effectively participate in New York’s political process. They would prefer to register with a party that aligns better with their values and preferences, not register strategically to have a say in the Democratic primary. Support for such measures has increased significantly among Democrats and Republicans alike, suggesting increased dissatisfaction with the status quo between 2024 and 2025.

Our results show that broad support exists in NYC for a range of electoral reforms other than primary changes, including RCV, even-year local elections, and on-ballot endorsements, though to varying degrees. Democrats’ strong support for RCV was 10 points higher in 2025 than in 2024. Republicans, by contrast, were more likely to somewhat support RCV in 2025 by an additional margin of 11 points over 2024. Even so, Republican opposition to RCV remained relatively high in both 2024 (47%) and 2025 (49%).

Republicans’ relative aversion to RCV, compared with primary reform, suggests that some New Yorkers do not support electoral reform indiscriminately, but have nuanced views. Some may oppose RCV but favor ending closed primaries for open or nonpartisan alternatives. The share of Republicans unsure of whether to continue RCV dropped from 26% in 2024 to 9% in 2025. Over the same period, Republicans increased both the share who somewhat support the continued use of RCV (+9 percentage points) and the share who somewhat oppose (+6 percentage points).

Broad appeal for the experimental reform to add endorsements on ballots complements voters’ preference for open or nonpartisan primaries. These endorsements would effectively serve as a richer and more immediate information cue to help voters make their decisions. Noteworthy is the additional 11% of voters who strongly supported the idea in 2025 compared with the year prior, and the 15% fewer voters who strongly opposed it, suggesting that more voters wish to have more information at their fingertips at the ballot box.

Voters’ openness to a range of electoral reforms is especially valuable to the 2025 Charter Revision Commission, currently considering reforms such as nonpartisan primaries and even-year local elections. The adoption of the polled reforms could significantly alter the political landscape of NYC. By fostering greater competition and participation, these changes have the potential to promote broad political engagement from the public. In turn, this engagement could produce local government that is more representative of New Yorkers’ preferences and priorities and more attuned to the multifaceted needs and interests of New Yorkers across the five boroughs.

The successful passage of electoral reform could lead to greater policy innovation. Subgroups of the electorate might form issues-focused or even single-issue campaigns about specific reforms, such as enabling new housing construction—an “Abundance New York” platform, for example. State Senator Zellnor Myrie’s campaign for mayor demonstrates that some candidates are ready to adopt such a platform.[29] Myrie’s campaign, which has failed to gain significant traction, is probably limited by the primary restriction to Democratic voters. Nonpartisan primaries could allow candidates like him to appeal across partisan lines and to unaffiliated voters.

For housing construction, a nonpartisan system could promote supply growth by allowing candidates to appeal to loosely organized “Yes-In-My-Backyard” voters from all political stripes. Pro-growth candidates and parties could promise to support residential rezonings and higher zoned densities (and in council races, promise to abstain from using the council member’s informal veto power called “member deference”).[30]

In particular, if primary reform is combined with even-year elections, the increased turnout and openness would reduce the inordinate influence of organized special interests, such as public-sector unions and trade groups. Currently, unions like the Hotel Trades Council exert enormous control over city politics, allowing them to gain supply-constraining concessions, such as requiring a vote of the city council to approve a new hotel application (which effectively forces applicants to use union labor exclusively).[31] With increased turnout, the voting body would be larger and more diverse, and candidates could build support from more constituencies, weakening special interests’ ability to decide who wins. Higher turnout can also make it harder and more expensive for these groups to reach enough voters to influence an election, relative to the status quo.

Nonetheless, reformers face several headwinds. A proposed charter amendment for nonpartisan elections and even-year elections will likely engender opposition from well-funded special interests, similar to the 2003 effort to introduce nonpartisan elections. Nearly half of those surveyed (49%) and pluralities of both parties still favored a traditional intra-party primary option, whether open or closed.

Conclusion

The Manhattan Institute’s survey reveals that New Yorkers largely support reforming their city’s stagnant electoral system. In an era of fierce competition among U.S. cities for the best talent and most productive firms, NYC needs robust accountability to achieve better results. Electoral reform can help achieve that aim.

The demand for change is clear and the tools for reform are within reach, provided that the political will exists to see through change. The 2025 Charter Revision Commission promises to deliver on some of these changes. The poll’s findings and proposals offer a valuable framework for rethinking and revitalizing the city’s electoral system in ways that could have lasting positive impacts on governance and civic engagement.

Endnotes

Photo by VINCENT ALBAN/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link