Life, Liberty, Property #111: Powell Beats Labor Market

Forward this issue to your friends and urge them to subscribe.

Read all Life, Liberty, Property articles here, and full issues here and here.

IN THIS ISSUE:

- Powell Beats Labor Market

- Video of the Week: Can Trump Dismantle the Deep State? – In The Tank #505

- Could Trump Rescue the Supreme Court?

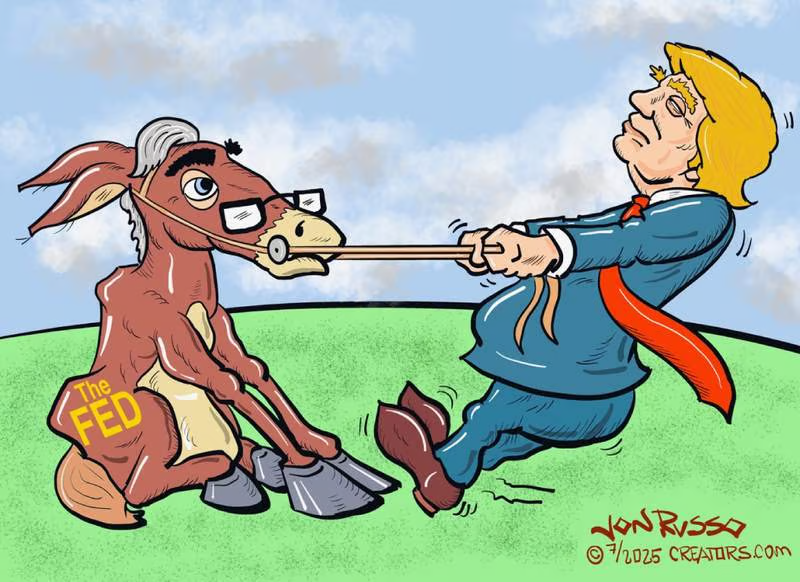

- Cartoon

- Bonus Video of the Week: The End of Official Climate Alarmism (Guest: Dr. Judith Curry) – The Climate Realism Show #167

Powell Beats Labor Market

Fed Chair Jerome Powell wants a slow labor market.

Two days after Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell announced the central bank’s decision not to reduce interest rates, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced bad news about the U.S. economy. Employers added many fewer jobs than expected in July, revised numbers showed that employment and hiring were weak in May and June, and the unemployment rate ticked up again in July, reaching 4.2 percent.

The economy added 73,000 jobs in July, far below the 110,000 economists had expected.

The original numbers for May and June were wild overestimates, The Washington Post reports:

Large cuts to earlier job counts erased 258,000 positions originally reported for May and June. Friday’s revised tallies were the biggest two-month downward revisions in modern history outside of the pandemic.

The revisions cut the reported job-addition totals for May and June from a healthy 291,000 to a dismal 33,000.

President Trump announced the firing of BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer on Friday, shortly after the new numbers were announced. “She will be replaced with someone much more competent and qualified,” Trump wrote in a Truth Social post.

That will be widely characterized as “retaliation” and “killing the messenger,” I’m sure. However, the BLS and other federal agencies regularly painted misleading economic pictures throughout the Biden years, reporting rosy, positive numbers and then correcting them a month later when everyone’s attention was diverted by the next set of false, overly positive numbers. I wrote about that regularly last year, and I welcome the president’s decision to hold someone responsible for those falsehoods, hoping that it is merely the first of many such.

Trump has also been regularly discussing his displeasure with the performance of Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell. The central bank certainly helped make Trump’s case on Wednesday, although presumably without intending to do so. Powell announced that the Fed would hold the fed funds rate steady for at least another month, thus keeping interest rates 54 times higher than they were early in the Biden administration (0.08 then, 4.33 percent now).

I cite those numbers merely for comparison, as I do not approve of zero or near-zero interest rates. Clearly, however, there is a lot of room for rate cuts without approaching irresponsible NZIRP levels.

The economy has clearly been wobbly since January 2021 under the tax-and-spend-and-borrow-greedily Biden-era fiscal policies. The positive effects of the recent extension of the 2017 tax cuts and the Trump administration’s rapid moves to deregulate industry and energy have been offset by worries about tariff effects and the necessary time lag between economic liberalization and the growth it inevitably fosters.

All of this was evident long before Friday, even though an assortment of official numbers indicated the economy was beginning to struggle out of the Biden-era doldrums. While strongly endorsing the tax cut extension and deregulation and arguing that they will go far in reviving the economy, I have continually expressed my concerns that the Fed would thwart a full recovery by keeping interest rates too high, making that argument again in last week’s issue of this newsletter.

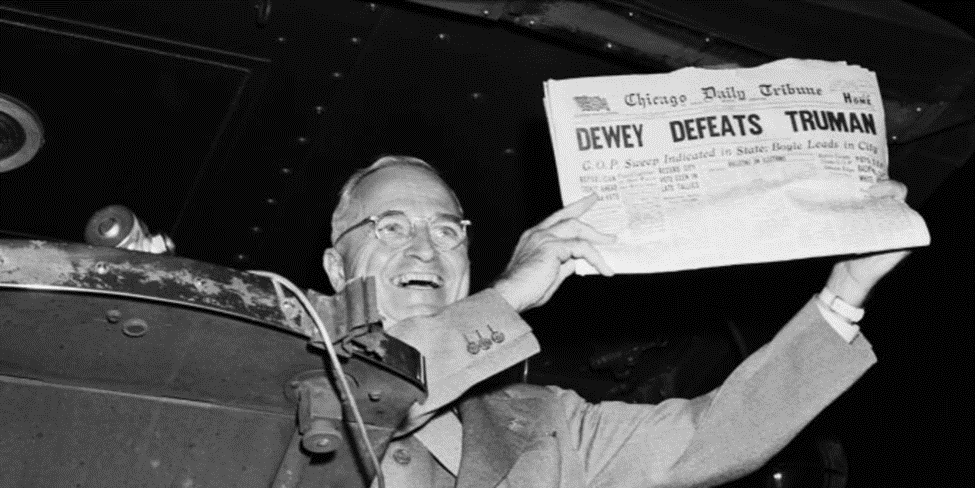

Unfortunately, that appears to be coming to pass. In an impressive “Dewey Defeats Truman” moment, Powell on Wednesday said the Fed was not ready to lower interest rates because unemployment is low and inflation is slightly above the Fed’s stated goal of 2 percent a year. That is interesting because the Fed lowered its target interest rate three times last fall, to its current level, even though inflation remained “somewhat elevated” at the time, as the Fed put it.

Powell has regularly argued that President Donald Trump’s tariffs will unleash inflation and that the labor market is strong, which he perceives as another potential source of inflation.

Both of those arguments ignore the simple fact that inflation is a general rise in prices, not price increases in specific sectors of the economy. If tariffs cause the prices of imported goods to rise, prices of other things must fall, unless someone increases the overall money supply—and that would have to be the Federal Reserve itself. The central bank has been doing the opposite since last summer, it is important to note: even when it cut the federal funds rate last fall, the Fed still kept selling securities, which tightens the money supply … and raises interest rates.

Similarly, if wages rise, it must be because productivity is rising, or businesses would not be able to afford to pay higher wages—unless somebody increases the overall money supply, which again points to the Fed. If businesses decide to pay the higher wages even if output per worker is not rising, prices of other things must fall, because that money is no longer available for purchasing or investing in those things—unless the central bank increases the money supply.

Try as he might, Powell cannot exonerate the Fed for the struggles with inflation. Still, he persists, blaming tariffs and workers for the slightly elevated inflation which is in fact simply a holdover from the Biden administration’s massive expansion of the federal deficit that the Fed monetized, increasing the money supply by 12.3 percent between January 2021 and April 2022 and holding the fed funds rate around 0.08 percent until March 18, 2022, when it raised it to 0.33 percent. The rate is now 4.33 percent.

“You do not see a weakness in the labor market,” Powell said in his Wednesday press conference, two days before the dismal truth about the labor market was released. “Demand for workers is growing, but so is the supply. … Wages are gradually cooling.”

We now know why wages have been cooling while the labor market was strong: the labor market was not strong. Powell and the Fed have been doing their best to stunt economic growth. They are succeeding at that.

Sources: The Washington Post; The Washington Post

Video of the Week

| Over just the last seven months, Trump’s administration has landed one blow after another on the administrative state and “deep state.” Most recently, Trump’s EPA and Department of Energy teamed up to announce a pending repeal of the greenhouse gas Endangerment Finding, which has allowed the government to regulate nearly every aspect of our lives since its passage in 2009.

Democrats still try their best to “resist” the Trump administration—either petulantly, like Cory Booker’s grandstanding, or through activist judges. All of it began with the Russia Hoax, which we are still unraveling. Meanwhile, on the culture war front: Leftists are losing it over an ad series put out by American Eagle featuring Sydney Sweeney and a pun involving “great jeans.” They claim this is literal fascism, and we wonder if it’s another sign that “woke” is falling out of favor in media. |

Could Trump Rescue the Supreme Court?

The increasing trend of lower-court judges openly defying the U.S. Supreme Court to thwart President Donald Trump’s agenda has sparked a cautious discussion of whether the Constitution requires a U.S. president to enforce laws he considers to be unconstitutional.

Writing at The New York Times, Harvard Law School professor and Catholic integralist thinker Adrian Vermeule summarizes the situation:

District Court judges, and in some cases even appellate courts, have either defied orders of the court outright or engaged in malicious compliance and evasion of those orders, in transparent bad faith.

In the past decade or so, increasing judicial overreach has caused harm to our constitutional order by limiting the ability of the executive branch to implement the program it was elected by the American people to pursue. It has been a scourge for both recent Republican and Democratic presidents, and it may provoke extreme measures to restore order. The recent defiance goes even further, threatening to damage the internal integrity of the judiciary, which ultimately relies on lower courts to follow the Supreme Court’s direction.

Vermeule recounts several examples, with which the reader is undoubtedly familiar, and characterizes the judges as out of control. “District Court judges have almost no accountability; they are like feudal lords who lay down the law in their local courts,” Vermeule writes. In addition, “any judge who breaks ground in limiting core presidential powers … becomes a hero among legal commentators and academics, depending on the ideological direction of the ruling,” the Harvard constitutional scholar observes.

These actions undermine the authority of the U.S. Supreme Court, which has the constitutional duty to manage the lower courts. Vermeule writes,

What is significant about these episodes is not merely that the lower-court judges are showboating, but that they are doing so at the expense of the Supreme Court. Overall, the federal judiciary suffers from a kind of collective-action problem. The whole institution bears the costs of disruption and diminished credibility from such lower-court defiance, while individual judges reap ideological acclaim and self-indulgence.

Some legal analysts and constitutional scholars have called for various measures such as limiting the authority of these lower courts and mandating three-judge district courts for cases that interpret federal statutes and executive orders. These reforms would have to be passed by Congress, however, which would “require a degree of congressional consensus that does not exist,” Vermeule notes, and would not arrive soon enough to “address the immediate reality that a legitimately elected president’s policy program is, right now, being stymied by judges defying not only the law, but the Supreme Court.”

The Supreme Court exercises authority over these lower courts, and the Roberts Court has issued multiple decisions striking down many of these lower-court rulings. “The Supreme Court recently limited universal injunctions in Trump v. CASA, but that only addresses part of the problem,” Vermeule writes. “The decision does not apply to the critically important category of suits under the Administrative Procedure Act, and lower courts have already begun to undermine the decision by certifying absurdly broad class-action suits.”

The Supreme Court decisions have proven insufficient to hold back the flood of unconstitutional lower-court intrusions into the authority of the Executive Branch under Article II of the Constitution, especially with the Supreme Court now out of session, as Vermeule observes:

What Chief Justice John Roberts optimistically called “the normal appellate process” cannot function well when lower courts ignore or circumvent the court’s orders. In practice, the court cannot review everything that defiant lower courts do, and for the president, justice repeatedly delayed curtails his ability to govern.

With the Supreme Court falling short in its duty to manage the lower courts, and those inferior courts undermining the high court’s authority through open defiance, the judicial system is in a truly precarious position, its credibility under mortal attack. Vermeule thus raises the idea that the president could exercise constitutional authority to step in to rescue the Supreme Court and the Executive Branch alike:

The final recourse in the system—a controversial and rarely used fallback—is what is described in constitutional theory as “departmentalism”: The president may ignore a judicial order that, on the president’s independent interpretation of the law, exceeds the scope of judicial power, as when a District Court were to purport to bar the president from granting a pardon or vetoing a bill. As my Harvard colleague Jack Goldsmith recently wrote, the theory has “a long pedigree in American history.”

“The basic theory of departmentalism is that while the Supreme Court has the authority to exercise its Article III ‘judicial Power’ in cases or controversies before it,” Mr. Goldsmith wrote, “the President’s Article II duty to ‘take care that the law be faithfully executed’ gives him an independent power to determine what ‘the law,’ including the Constitution, means, for purposes of exercising executive power.”

Alexander Hamilton, writing in the Federalist Papers, described that possibility as one of the main checks on the judiciary created by the constitutional system of divided powers.

“Presidents Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt all embraced a version of departmentalism,” and “executive branch agency defiance of lower court judicial decisions is more commonplace than is appreciated,” wrote former senior government lawyer Jack Goldsmith in February.

Nonetheless, Goldsmith writes, “despite departmentalism’s long pedigree, it is a remarkable feature of our constitutional practice that no president has ever defied a Supreme Court judgment. Just as remarkably, presidents have, with scattered exceptions in extreme contexts—mainly, Lincoln’s actions in defiance of the principles of Dred Scott during the Civil War—respected Supreme Court precedent even as they sought to convince the Court to adopt a different view.”

Those observations suggest that Trump would be on solid ground in overruling at least the most egregious lower-court rulings on constitutional grounds, as long as the president’s actions do not conflict with decisions by the Supreme Court. (Some constitutional scholars argue that the president is not bound even by Supreme Court interpretations of federal law, but Trump need not engage in that debate at present.)

Even with this constitutional and historical support, open presidential defiance of even a carefully selected set of lower-court decisions now would be highly controversial, especially given the explicit opposition and open hatred of Trump that has suffused the nation’s media and other institutions. Vermeule writes,

The general merits of departmentalism are much debated. It is strong medicine that risks doing more harm than good overall, and that by its nature requires controversial judgments by the executive.

But whatever its usual merits, the case for it here is different and unusually strong. When a lower court’s order attempting to limit the executive is also an act of mutiny against the Supreme Court, the issue is not conflict between branches, but the legitimate hierarchy of authority within the judicial branch.

By ignoring such an order, the president, far from defying the judiciary as such, would be supporting the authority of the Supreme Court—the only court created by the Constitution itself.

Vermeule is right to offer words of caution even as he suggests the president consider such a confrontation. At least one member of Congress has already called for Trump to be impeached over the deportation of alleged MS-13 member Kilmar Garcia in April. Impeachment and removal from office are exceedingly unlikely even with the present tight GOP majorities in Congress. However, it is obvious that Democrats might happily impeach Trump over presidential defiance of lower-court decisions should they regain majorities in the 2026 elections, and they would certainly try to use that to their advantage in their campaigns.

I surmise that such a scenario is one very good reason the Trump administration has been punctilious about finding legal justifications for its actions, carefully choosing wording and arguments that make reasonably credible if sometimes suspiciously clever cases that they are following the law. Trump’s team has also been receiving fairly decent support from the Supreme Court, especially in emergency cases, which are even more important when the Court is out of session.

Those factors have so far averted any open challenges by the Trump administration. That could change after November 3 of next year if the Supreme Court fails to take further measures to rein in the inferior courts.

Source: The New York Times

NEW Heartland Policy Study

‘The CSDDD is the greatest threat to America’s sovereignty since the fall of the Soviet Union.’

Cartoon

via Townhall

Bonus Video of the Week

This is a historic week—historically catastrophic for climate alarmists who have bullied their way through every institution in the United States and around the world. Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency formally announced, at long last, that it will repeal the so-called “Endangerment Finding” for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The EPA has determined that GHGs are not pollution and that their emissions from human activity do not pose a threat to human health. On the same day, Trump’s Department of Energy released a “critical review of impacts of GHG emissions on the U.S. climate.” This marks the first time ever that a climate report from the federal government can withstand scientific scrutiny, as it is based on actual science and data rather than politics or any particular agenda.

Contact Us

The Heartland Institute

3939 North Wilke Road

Arlington Heights, IL 60004

p: 312/377-4000

f: 312/277-4122

e: [email protected]

Website: Heartland.org