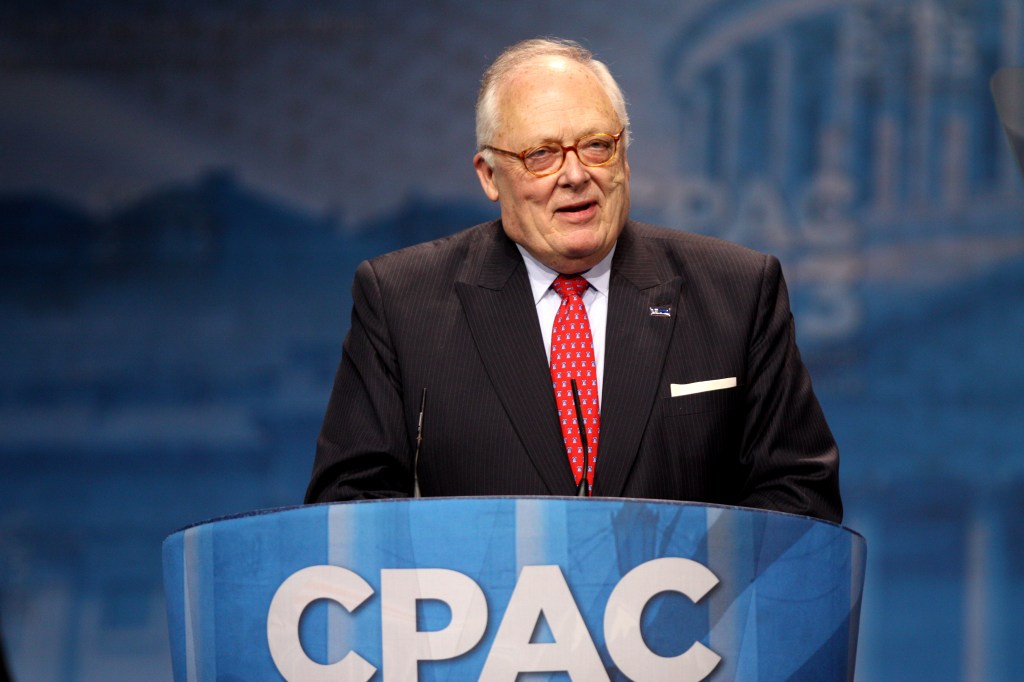

Ed Feulner, who passed away this month, co-founded the Heritage Foundation in 1973 and built it into the most influential conservative institution in American politics. That much is well known. What’s less often appreciated is what animated his success—not just his intellectual brilliance or strategic insight, but something far rarer today: joy. Ed was cheerful, gracious, and relentlessly optimistic about America and the conservative cause—and that is precisely what made his impact so profound.

We live in a time when political despair is in fashion. From cable news panels to the endless scroll of social media, a common refrain dominates: Everything is broken, the system is rigged, nothing can be trusted. Some on the right have taken this pessimism so far that they now question even our constitutional order and the principles of liberty that have defined American conservatism for generations.

That was never Ed Feulner’s mindset. He was no stranger to political setbacks—from Barry Goldwater’s defeat in 1964, to President George H.W. Bush’s reversal on taxes, to the rise of the Clinton dynasty, to progressive majorities in Congress and the courts. But Ed never saw momentary defeat as a reason to discard principle, or his optimistic worldview.

In fact, many of his most important contributions were born during seasons when optimism seemed in short supply. In the early 1970s, there was no rational case for founding a conservative think tank. The New Deal consensus was dominant and progressivism held the high ground. Yet Ed launched Heritage with a deep conviction that conservative ideas—if communicated clearly and relentlessly—could change the trajectory of the country. He turned out to be right.

Time and again, Ed responded to setback not with despair but with creativity. In 1994, he launched Townhall.com, one of the earliest digital platforms for conservative commentary. In 2001, he spearheaded a drive to recruit a million Heritage members—a staggering goal at the time. In 2005, he helped revamp the Center for Media and Public Policy to focus on new media and the emerging blogosphere, and it eventually became the Heritage Foundation’s media powerhouse. And in 2010, he helped launch Heritage Action for America, believing that policy expertise needed to be matched by citizen engagement.

These weren’t gimmicks. They were serious, forward-thinking responses to a shifting political landscape. Ed was always willing to rethink strategy—but never to abandon principle. That distinction is vital. In moments of uncertainty, Ed did what conservatives are supposed to do: innovate tactically while remaining anchored philosophically.

Why was he able to do that? Because Ed’s conservatism, at its core, was a posture of gratitude. He believed in the accumulated wisdom of those who came before us—the imperfect men and women who, despite their flaws, helped build the American experiment. He knew that we stood on the shoulders of giants. And he saw our task not as tearing it all down, but as preserving and refining it for the next generation.

This is where conservatism diverges most clearly from progressivism. Where progressivism often begins in contempt—for tradition, for inherited values, for the moral judgments of the past—conservatism begins in gratitude. It acknowledges the brokenness of human nature but sees enduring value in the institutions, norms, and ideals passed down to us. Ed believed that conservative ideas were not only morally right, but naturally resilient—because they were rooted in human nature, not utopian theory.

That’s why Ed could remain hopeful even when others gave in to cynicism. He trusted the American people. He trusted the genius of the Founders. And he believed that timeless truths endure, even when a culture tries to forget them.

In an age that too often rewards outrage over wisdom, Ed’s good cheer stood out. He proved that you could be principled without being bitter, and serious without being grim. He reminded us that the work of conservatism must also be the work of joy.

Conservatives have lost a statesman and strategist. But most of all, we’ve lost one of the great optimists of our time. We would do well to recover his spirit.