You’re reading Dispatch Culture, our new weekly newsletter exploring the world beyond politics. To unlock all of our stories, podcasts, community benefits, and our newest feature, Dispatch Voiced, which allows you to listen to our written stories in your own podcast feed, join The Dispatch as a paying member.

I hope everyone had a good week, and I hope that, if you got hit with winter weather, your towns and cities handled it better than D.C. did. This weekend, we have a rich smattering of non-politics for you, starting off with Dispatch Contributing Writer LuElla D’Amico, who writes about how celebrity drama, while sometimes trivial, can help us decide what we want for our own families. “These stories let us explore questions about loyalty, forgiveness, boundaries, and respect without naming names at our great uncle’s 75th birthday party,” she writes. “Through someone else’s family drama, we test our own moral instincts.”

Next up, we have Nadya Williams on a new book that marries two arts: translating and mothering. “Books can be translated, but can the experience of motherhood?” Williams writes. “A.’s mourning suggests that no matter how desperately she tries, she is not sure she has succeeded in fully understanding the mothers. Perhaps motherhood cannot be translated, only experienced.”

Finally, we have something you may not be expecting: Madeleine Lawson on the hit TV show Heated Rivalry. Now, this is not The Dispatch’s usual fare. But Lawson writes that the show is an interesting study in how traditional storytelling techniques are once again proving their bona fides. “Heated Rivalry is, in essence, a comforting return to the basics of romance: Two attractive, talented people who are somehow at odds notice each other’s massive sex appeal and consent to test the waters, risk be damned,” Lawson writes. “The bone structure here is sturdy and recognizable.”

From earlier in the week, we have Pepperdine University professor Jessica Hooten Wilson on the Western canon, Dispatch Senior Editor Michael Warren with a profile on a rabble-rousing Georgia woman, and new Dispatch Contributing Writer Emmett Rensin on how the word “fascism” seems to have gained supernatural powers in American society. That’s all!

American Artifacts

Born in either Ohio or upstate New York in 1844 to a free black father and a mother who claimed Chippewa roots, Edmonia Lewis was orphaned as a young girl. She was raised by aunts in New York, and other relatives, seeing that she was bright, financed her education. A Catholic, she was educated by an order of black nuns in Baltimore and was eventually accepted into what would become Oberlin College in Ohio. Oberlin was one of the earliest colleges to admit black women, but she nonetheless experienced discrimination there. Another female student accused her of poisoning her wine (a charge for which she was acquitted) and in response a group of white students kidnapped her, beat her, and left her on the side of the road. At Oberlin she studied art, but was mostly self-taught, specializing in sculpted portraiture.

Like other black artists of the era, she found life easier in Europe. She eventually moved to Rome and opened a studio in Piazza Barberini. In Rome, she felt she didn’t constantly have to be reminded she was black: Italy, having never yet been a colonial power, nor having played as significant part in the international slave trade, did not have the strict color barriers found in much of America.

When the issue of race did come up, Lewis was affronted by those who would comment that her sculptures were marvelous and impressive “for a black woman.” “Some praise me because I am a colored girl,” she said, “and I don’t want that kind of praise. I had rather you would point out my defects, for that will teach me something.” She took as her subjects black and Native American sitters, as well as the classical figures of antiquity. President Ulysses S. Grant even sat for a (now lost) portrait. Some of her most famous works, like The Death of Cleopatra, can be seen today in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

Lewis, like the poet Phillis Wheatley, was significant in destabilizing the widespread assumption that black people were somehow of inferior intelligence and character. Wheatley was a slave for much of her life and wrote poetry in the classical vein, extolling the cardinal virtues. When her verses were published in a newspaper, some readers thought it was a scam. How could a young slave write such noble, beautiful lines?

Wheatley wrote an eloquent poem in praise of George Washington and sent it to him. In “His Excellency General Washington,” Wheatley narrated the present course of the Revolutionary War, and looked in hope toward a freer future:

Fix’d are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.

Anon Britannia droops the pensive head,

While round increase the rising hills of dead.

Ah! Cruel blindness to Columbia’s state!

Lament thy thirst of boundless power too late.

Rather than tossing aside a letter from a slave girl, Washington wrote a letter in reply that deserves to be quoted at length.

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. In honour of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the Poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the World this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of Vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public Prints.If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favourd by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great Respect, Your obedient humble servant, G. Washington

No person should have to prove that they are a great artist in order to be accorded the dignity due to them simply because they are human. But these women of genius did find that beauty could speak over and above prejudice, and indeed, could crack into calcified hearts and minds. At the same time, like Frederick Douglass, these women found a kind of liberty in art and the life of the mind. In the resources of the Western tradition itself they found threads of freedom, virtue, and dignity. In seeking out and identifying beauty, rather than being swallowed by hatred or bitterness, they advanced the cause of a more just society.

These figures are a part of our heritage as Americans. It is worth remembering, valuing, and appreciating their work, not because a DEI obligation tells us to do so, but because they are genuinely valuable parts of our national inheritance. They might prompt us to ask, under oppressive circumstances could we, too, make a work of beauty for the world?

An Outside Read

The Atlantic’s James Parker wrote this week on a marathon reading of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick that takes place every year at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts—and which takes, he notes, 25 hours. But those 25 hours see many readers take the stage, and the readers, Parker writes, are panoply of America. “They have every quality. They are stammering, assured, dubious, virtuosic, inaudible, room-shaking, thick-voiced, thin-voiced, professional, innocent, mesmerizing, devoid of presence,” Parker writes. “It’s an American pageant, purely democratic, intensely moving. Reader by reader, the thread of meaning, the pulse, comes and goes. Some of them seem to seize us by the very roots of our comprehension; others might as well be reading from the Terms and Conditions of Use for Spotify. The prose of Moby-Dick is dense; it can be unwieldy—Melville’s mouthfuls are too large for our 21st-century mandibles. Some words that people have trouble with: idolator, remonstrances, vicissitudes, magnanimity, portentousness. Also (this one surprises me): leviathan.”

Stuff We Like

By Charlotte Lawson, associate editor

This week, I was taking my dog Ollie for his morning stroll when I saw something strange: an iguana lying perfectly still in my neighbor’s yard. But it wasn’t dead—it was frozen. Apparently when the temperature drops below 50 degrees here in South Florida, iguanas (an invasive species) can’t bear the low temperatures and start dropping out of trees. How relatable. Fortunately, most of the fallen reptiles eventually thaw out and resume their lives.

Which brings me to the thing I like: South Florida. I moved here in search of a warm climate, but found way more wonderful weirdness than I could have anticipated. A guy on food stamps bragging about his bowrider boat to the gas station cashier. Fire jugglers showing up for practice in the parking lot of a local pub. Packs of roller skaters competing with Aston Martins for road space. Multiple Japanese-Peruvian fusion restaurants? Add to that a stunning natural environment, and it’s easy to see why so many folks want to live down here. I just hope the temperature rises again soon, lest I go the way of the iguana.

Work of the Week

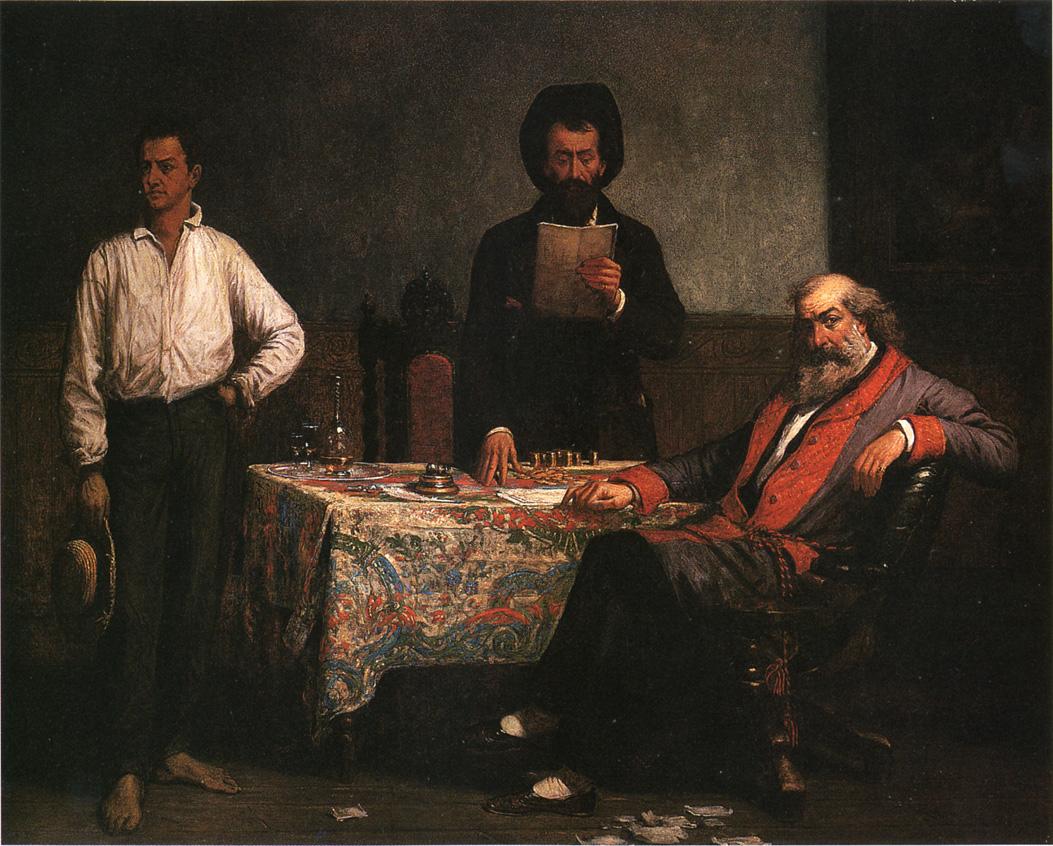

Work: The Price of Blood, by Thomas Satterwhite Noble, 1868

Why I’m a Dispatch member: Because I’m a politically homeless conservative and it’s good to hear from others.

Why I chose this work: The son of a slaveholding Kentucky family and a captain in the Confederate army, Noble was nevertheless a passionately anti-slavery painter. In this work, (painted after Emancipation) a slaveholder is shown selling his mulatto son.

Interested in being featured in this section? Submit a work of art here.

Interested in being featured in this section? Become a Dispatch member here.