Even before the ink dried on the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), many Republican lawmakers were excitedly discussing the possibility of another reconciliation bill. To these conservative lawmakers, Reconciliation 2.0 could include all the deep spending savings that failed to make it into Reconciliation 1.0 (the OBBBA). Indeed, the House Republican Study Committee (RSC) recently released a Reconciliation 2.0 blueprint that it claims would save $1 trillion over the decade.

Budget savings are desperately needed to combat unsustainable budget deficits heading toward $4 trillion annually within the next decade. Nevertheless, fiscal conservatives and deficit hawks should be strongly skeptical of Reconciliation 2.0. Given the still-shrinking House GOP majority and a critical midterm election approaching, such legislation is overwhelmingly likely to be twisted into another cynical vote-buying indulgence of tax relief and spending expansions. After all, the reconciliation process has produced the overwhelming majority of deficit-expanding legislation over the past quarter-century, and there is no basis for trusting the current Republican government to suddenly use it for courageous (and politically risky) budget cuts before the 2026 election.

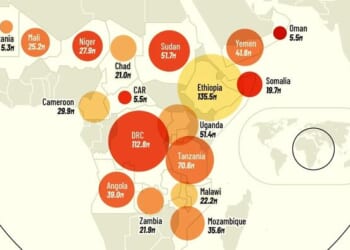

Previous reconciliation laws added $16 trillion to the debt.

The temptation of another reconciliation bill is understandable because such bills can pass under an expedited process that a Senate minority cannot filibuster. Broad reconciliation bills are generally limited to one per fiscal year, as long as Congress is willing to first draft and pass a budget resolution (from which the reconciliation instructions spin off). Thus, Congress could perform this exercise once for FY 2026 (which ends on September 30) and then potentially again after the next fiscal year begins on October 1.

Parties with unified control of Congress and the White House seldom let reconciliation opportunities go to waste, as the rule protecting such bills from a Senate filibuster essentially renders the minority party powerless. And while this filibuster-proof privilege was originally intended to facilitate the passage of deficit-reducing legislation, it has since been twisted into a “get out of jail free” card providing the majority party with one annual bill to pack with all the budget-busting tax cuts and spending hikes they could never pass under regular order.

Accordingly, since 2001, the five largest reconciliation laws (plus the 2013 non-reconciliation extension of the reconciliation-passed Bush tax reductions) have cost a staggering $12.8 trillion plus $3 trillion in resulting interest costs for a total of $15.8 trillion in added government debt. This includes two President Bush tax cut bills (2001 and 2003) and one permanent extension of that tax relief (2013), two President Trump tax reductions (2017 and 2025), and President Biden’s American Rescue Plan (2021). Far from facilitating the passage of deficit-reduction bills, the reconciliation process has become a colossal deficit driver.

Deficit hawks were routed in Reconciliation 1.0.

Which brings us to the current Congress. A year ago, as congressional Republicans began drafting legislation to extend the 2017 tax cuts, many expressed concerns over the $4 trillion 10-year price tag of a pure extension. Consequently, GOP lawmakers across the House Budget Committee, Senate Budget Committee, and House Freedom Caucus began meeting and exchanging potential spending reductions and tax loophole closures to offset much of the extension. The House even passed a budget resolution capping the tax cuts and requiring up to $2 trillion in offsetting spending savings. Ultimately, these lawmakers were steamrolled, and the OBBBA’s price tag significantly rose—rather than fell—during the legislative process.

While legislative Republicans have long talked a good game on spending and deficit savings, the challenge of producing substantial offsets that could garner the support of 217 of the 220 House Republicans often proved insurmountable (vacancies left the House with only 432 lawmakers, so 217 votes were required for passage). Even in the Senate, Republicans could lose no more than three of their 53 members.

Thus, farm state Republicans not only blocked cuts to farm subsidies and rural hospitals, they won major expansions of the programs. Lawmakers from wealthier states would not accept more than minor limits on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, while representatives of poorer states opposed more aggressive Medicaid and SNAP savings. In other instances, broad calls to combat government waste or drastically slash funding for welfare, immigrants, and foreigners were revealed as unworkable, impractical, or capable of saving far less money than initially promised.

Hovering above these congressional GOP debates was President Trump. Waving off any deficit concerns, the president took Social Security and Medicare (and occasionally Medicaid) savings off the table, supported nearly $300 billion in additional defense and border spending, and demanded his own additional tax cuts for overtime, tips, auto loan interest, and senior citizens. While Republican deficit hawks expressed concerns over the OBBBA’s swelling price tag, the vast majority were not about to commit political suicide by crossing Trump or endangering his prized bill. This robbed these lawmakers of any leverage to force larger offsets, leading them to pass a bill projected to cost $5 trillion over the decade if extended.

Reconciliation 2.0 would surely add more debt.

This buyer’s remorse from fiscal conservatives has fueled calls for Reconciliation 2.0 to finally offset some of the OBBBA’s cost. Yet these GOP fiscal hawks have failed to articulate why an aggressive package of spending cuts that could not pass last year—even when quietly buried inside a sprawling, must-pass bill with popular tax cuts—will suddenly win 217 GOP votes while leading an eat-your-spinach reconciliation bill that faces much less pressure to make it over the finish line. Moreover, how will they suddenly achieve the near-unanimous GOP legislative support for these unpopular provisions (if they were popular, they’d have been included in last year’s bill) with possibly an even smaller House majority than in 2025, and right before a midterm election? The idea that a vulnerable GOP majority will team up with President Trump (who governs with no deficit concerns) to pass partisan legislation slashing benefits or raising taxes shortly before an election defies credulity.

We’ve been down this road before. While working as a Senate Republican economist during the Obama presidency, I witnessed or participated in several legislative working groups crafting bold revenue-neutral tax reform proposals. Then Trump was elected with a GOP Congress, and together they removed much of the spinach from these revenue-neutral proposals and instead passed a $1.5 trillion tax cut.

Nor was that experience unique. As a federal budget economist, I remain unable to identify a single major spending cut bill enacted by a unified Republican government since way back in 1954, when President Dwight Eisenhower persuaded a GOP Congress to trim post-Korean War military spending. Instead, GOP governments have typically paired aggressive tax relief with spending sprees. The only significant spending-cut law of the past 25 years—the 2011 Budget Control Act—was passed under divided government (and largely gutted soon after enactment).

So while conservative Republicans may push for Reconciliation 2.0 with the best of intentions, it is overwhelmingly likely that any initial savings provisions would be quickly jettisoned and replaced with new tax reductions and spending expansions to protect vulnerable Republicans up for reelection and give President Trump another budget-busting win. Consider Trump’s recent fiscal demands of: 1) a $500 billion increase in defense spending; 2) $2,000 tariff tax rebates at a cost of up to $600 billion; and 3) farmer bailouts in response to the tariffs. These expensive policies would surely move to the front of the line in any new reconciliation bill.

In addition to Trump’s proposals, congressional Republicans may also decide to protect themselves against having to negotiate with a potential Democratic Congress during President Trump’s next two years. This would mean raising the debt limit to a level that lasts until 2029 and attaching more multiyear discretionary appropriations that would allow congressional Republicans to be satisfied with continuing resolutions under a Democratic House or Senate.

The seeds of this outcome are already emerging. The Republican Study Committee has released a Reconciliation 2.0 proposal that (by their accounting) pairs $720 billion in new tax cuts with $210 billion in tax hikes and revenue raisers and $1.6 trillion in spending reductions. If history is any guide, Republican leadership will adopt many of the tax cuts while tossing aside nearly all savings policies (many of which are not particularly well-designed or plausible anyway).

Combining Trump’s military spending, farm bailouts, and tariff rebates with the RSC-proposed tax cuts, and potentially a short-term extension of expiring Affordable Care Act subsidies could easily push the cost of this reconciliation bill to between $1 trillion and $2 trillion. Fiscal hawks in Congress would undoubtedly express concerns, but how many would be willing to cast the deciding vote against President Trump and a bill that (in its new pandering form) would be considered key to protecting the Republican majority? The OBBBA experience likely answers that question.

Congressional Republican deficit hawks may push for Reconciliation 2.0 as an opportunity for overdue fiscal restraint. Yet once Trump and congressional Republican leadership adopt Reconciliation 2.0, they will take over the ownership of both the legislative process and the policies. Savings will likely be replaced with new spending, tax relief, and presidential priorities in a trillion-dollar Christmas tree of pre-election giveaways. Rather than leading an effort to reduce deficits, these lawmakers may once again find themselves facing suffocating pressure to pass budget-busting legislation out of presidential and party loyalty. The best way to stop this runaway train is to not let it out of the station in the first place. Unfortunately, there is not a sufficient presidential or congressional constituency for major spending cuts in 2026, and that means conservatives should not awaken the sleeping giant of reconciliation.