A key goal in writing this publication has been to provide a voice to those forgotten by medicine, so I try to respond to all the messages I receive—particularly those in dire need. However, as this publication has grown, it’s become more complex and more challenging for me to do that adequately due to the volume of correspondence I receive. I hence decided to have monthly open threads where readers can ask whatever they want and connect it to a shorter topic.

A few days ago, while talking to a circle of friends about child-rearing, one mother compared an infant’s tendency to throw tantrums when sugary foods were withdrawn to what many parents were facing with modern children’s video programs and that she’d learned in the groups she belonged to that numerous parents were now switching to showing their children the shows they’d grown up watching as those shows did not have the same destabilizing effects on their children.

As we discussed this topic (e.g., many of us have banned screens after noticing how negatively they impact developing nervous systems), I realized it needed to be an open thread here due to:

• How unfair and tragic it is that due to the modern toxicity they are bombarded with, so many children no longer have health and spark within them which brings joy to everyone around them.

• All the problems we discussed with children directly tie into the central issues I feel are facing much broader segments of society (e.g., the dopamine trap society uses to control us and make us feel dead inside).

Note: it continually astounds me (and those I point it out to) how different naturally raised children are, and how much rarer they are becoming, given the many fronts on which the predatory forces around us are attacking our health. For those interested, some of the most important strategies I’ve come across for raising healthy children are discussed here.

Addictive Programming

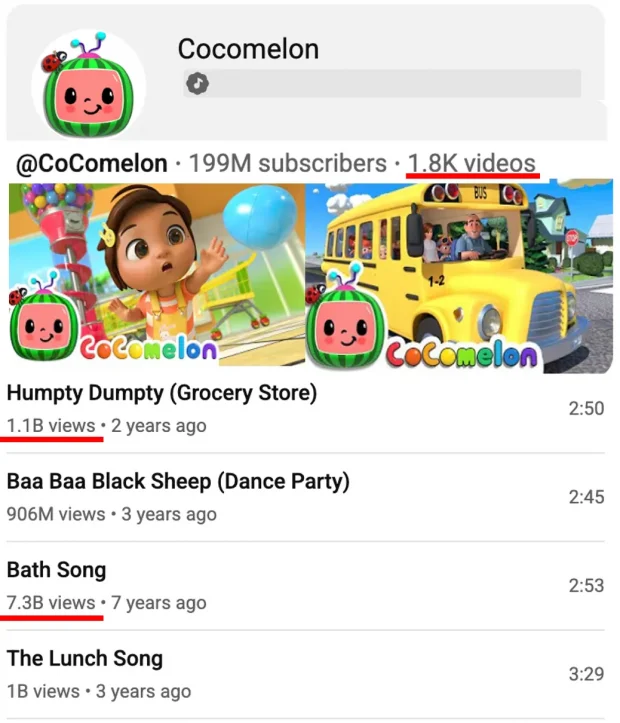

From investigating the current state of children’s programming over the last few days, I found out that large swathes of parents online frequently describe modern children’s “TV” content (particularly YouTube kids videos such as CoComelon) as highly engaging to the point of addiction, with intense emotional reactions (e.g., tantrums) when it’s removed. For example:

• A 2025 Talker Research survey of 2,000 U.S. parents found 22% report “full-on tantrums” as a side effect of excessive screen time, alongside irritability (27%) and mood swings (24%).

Note: this report has a lot of other disturbing statistics (e.g., 67% of parents fear they are losing precious time with their children due to screen addiction).

• The 2025 Common Sense Media Census states: “A quarter of parents use screen media of any kind (not just mobile devices) to help their child calm down when they are angry or upset (25%)” and “17% of parents reporting that their child sometimes or often uses a mobile device to calm down when feeling angry, sad, or upset.”

• In parallel, similar results can be found online. For example, on Reddit parenting forums, searches for “Cocomelon tantrum” or “screen time meltdown” yield a high volume of threads from the last 5 years (thousands according to two AI systems I queried), with parents describing similar patterns: calm during viewing, explosive tantrums (screaming, hitting, inconsolable crying for 20–60+ minutes) upon shutdown, that is often far worse than what was seen with slower shows like older Sesame Street.

• Pediatric resources like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) acknowledge these issues in their clinical guidelines, noting that high-engagement digital media (e.g., auto-advancing games or videos) can lead to tantrums when interrupted due to the media containing behavioral reinforcement designed for maximum engagement.

Furthermore, online reports from parents surged following 2015 as YouTube became much more popular and kids content there shifted to being optimized for toddlers to view without their parents. Research on the effects of overstimulation and attention, in turn, suggest this is addictive and creates ADHD-like symptoms as:

• Modern shows’ rapid cuts (1–4 seconds) overstimulate young children’s developing brains, making it hard for them to disengage and sustain focus on slower tasks (termed the “overstimulation hypothesis”).

•A 2011 study exposed 4-year-olds to 9 minutes of fast-paced SpongeBob SquarePants (11-second cuts) vs. slower Caillou or drawing; the fast-paced group showed immediate deficits in executive function (focus, self-control) lasting up to 4 hours post-viewing—which was not seen in the slower content.

Note: The AAP cites this in its guidelines, recommending that parents avoid fast-paced programs for kids under 5 due to poor comprehension and strain on regulation.

• A 2004 study of 1,278 kids found over 2 hours a day of TV before age 3 was linked to attention problems (e.g., ADHD-like symptoms) by age 7, with fast-paced content being a key factor.

• A 2018 review found early fast-paced exposure correlated with later attentional deficits, as it “rewires” developing brains toward novelty-seeking over sustained focus. Likewise in mice, excessive sensory stimulation decreased anxiety, learning, and memory and increased risk-taking and motor activity.

• A 2023 study linked higher toddler screen time to increased anger/frustration later (e.g., withdrawal tantrums), with each extra hour raising risk by 13%—specifically, preschooler screen time at age 3.5 prospectively contributed to more expressions of anger/frustration at 4.5.

Since many parents specifically cited CoComelon (a YouTube channel) as being particularly problematic (to the point many stated they’d banned it), and often attributed it to the show’s rapidly changing frames every few seconds, I watched a few of them to verify this (noting how disorienting it was to watch this as the shots frequently change every 1-4 seconds).

Note: many people I’ve spoken to over the years believe the shorter and shorter segments (before a screen cut or transition) which emerged on TV was immensely destructive to the American psyche as they took away people’s ability to maintain a lengthy attention span (which amongst other things is necessary to perceive the deeper things around which give true meaning to life or be content in the present).

After exploring why YouTube kids channels like CoComelon do this, I came across a series of explanations, which while appalling, are entirely congruent with my understanding of internet marketers:

• This maximizes “watch time” on YouTube (how they make money) as YouTube’s algorithm heavily rewards total minutes watched and session length. Very young children (1–4 years old) have naturally short attention spans. If a scene stays the same for more than a few seconds, toddlers often look away or grab the remote/phone. Rapid cuts act like a visual “ping” that yanks attention back to the screen every few seconds, increasing average view duration.

• Every sudden cut, zoom, color flash, or new sound triggers the brain’s automatic “orienting response” (the same reflex that makes you turn your head when a door slams). In babies and toddlers, this reflex is especially strong and hard to inhibit. CoComelon and similar channels appear to exploit it hundreds of times per episode, creating a near-constant dopamine loop that feels rewarding to an immature prefrontal cortex.

• It’s designed for the “auto-play” environment. On YouTube and Netflix, the following video starts in 3–6 seconds unless someone intervenes. Fast pacing makes kids much less likely to look away during that critical window, so autoplay chains them from one 8-15 minute video to the next (often for hours). This is likely why CoComelon uploads videos in the hundreds and titles them almost identically (as this creates an endless loop of their content).

• The big YouTube kids channels almost certainly constantly use available analytics to determine their pacing, colors, sound effects, and character design and most likely have found that cutting every ~2–3 seconds keeps 2- to 4-year-olds glued to the screen more effectively than slower pacing. Slower-paced versions tend to get lower completion rates and worse algorithmic performance, so they’re discarded.

• Classic slow-paced shows (Mister Rogers, old Sesame Street, Blue’s Clues), in contrast, were deliberately calm and used long takes because they were designed for developmental appropriateness (and were often watched with a parent). Modern YouTube-first content is intended to be watched alone by a toddler holding a tablet, with no adult co-viewing required, so “grab and hold attention at all costs” wins.

Note: Mister Rogers shared in interviews he would often leave a pause after he said things so children could have the time to process how they felt about it—effectively the polar opposite to what these channels are doing.

All of this has a startling number of implications. Of these, I believe the following are the most pertinent:

1. A large body of evidence has emerged (including numerous regretful statements from tech executives) that screens and all the content associated with them have been designed to be as addictive as possible, with much of this revolving around them having stimuli that trigger dopamine releases. In parallel, quite a few social media executives have said they have tremendous regret about what their products (intentionally designed to be addictive) have done to our children’s brains. Likewise, many articles have been written about how Silicon Valley tech executives send their kids to an alternative school where phones and screens are banned.

Note: as mentioned before, I am inclined to believe this is true, in part because I know marketers are always trying to concoct ways to hook people with their products (a process that has gone into overdrive since the internet has enabled the rapid testing, refinement, and distribution of addictive content) and partly because I frequently feel many of the ways tech messes with your neurology to pull you in (which again touches upon how unexpected it was for me to suddenly end up in a position where I had to spend a lot of time on the computer after this newsletter took off).

2. After the DPT vaccine entered the population, due to its frequent tendency to cause encephalitis, a wide range of neurological and behavioral issues (including violent crime) rippled out through the society as the vaccinated children grew up. In the 1950s, a condition termed “minimal brain damage” [MBD] was coined (with the defining characteristic of it being hyperactivity), which before long became “perhaps the most common, and certainly one of the most time-consuming problems in current pediatric practice”.

The symptoms of MBD (as defined by America’s Public Health Service and the American Psychiatric Association) have a significant overlap with what was seen after encephalitis, DPT injuries, and what was associated with autism. Eventually, they figured out that much of it could be “treated” with stimulants like amphetamines. At that point, the disorder was renamed ADHD (something that coincidentally, every vaccinated-unvaccinated comparison shows is vastly more common in vaccinated children).

Note: Canadian physician Gabor Maté has reported that a significant number of the homeless, often stimulant-using, addicted patients he worked with showed signs of undiagnosed ADHD. He (and others) have said that when their ADHD was recognized correctly and treated—usually as part of a broader trauma-informed approach (as he attributed this change to childhood trauma rather than vaccine injury)—it often helped them stabilize and reduce the destructive cycle of their addictions and the criminalized behaviors associated with them.

3. I have long suspected something similar to what happened with ADHD and amphetamines is happening with screens, as their highly stimulating (and dopamine-releasing) nature is essentially being used to counteract the behavioral disturbances seen in vaccine-injured children. This is particularly insidious because many parents (especially those with less financial resources) are frequently forced into situations where they don’t have the bandwidth to handle their children continually misbehaving, so they are forced to provide their children with addictive technology (and transform them into lifelong users).

Note: an argument can also be made that the mass adoption of screens is a reflection of the economy making it harder and harder for parents to have children.

4. I have long believed a key reason slavery ended was that owning slaves within America (which has numerous associated costs) became less profitable than forcing people into economic servitude, particularly since much of the labor slaves performed could be outsourced to poorer nations where far fewer protections existed for basic human welfare and that cruelty could exist out of sight and out of mind for those who would object to it.

In turn, since the desire to ruthlessly exploit people for profit never fully disappeared from the culture, other ways more profitable ways were found to do it, such as turning people into lifelong customers of the pharmaceutical industry until they eventually succumb to all the ever-increasing number of prescriptions they are placed on (a process which is often set in motion by the chronic illnesses frequently triggered by vaccination—and which I’ve recently heard be termed “biological colonialism”). To a large extent, I feel the same thing is also happening now with harvesting people’s attention online and collecting their data.

If we take a step back, consider that something many parents trust their children watch was actually designed and optimized to hijack their children regardless of the harm it caused their developing nervous system—and that rather than be penalized for this, it’s amassed billions of (lucrative) views because the algorithms content creators follow incentivize this type of quickly produced content.