You’re reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg’s biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Dear Reader (especially those of you considering a career switch),

I have a long-standing and consistent belief in the value of labels. My underrated second book was basically an extended discussion of how important words (concepts, language, labels) are for the work of civilization. My standard question for people who say they don’t believe in labels is some variation of, “Do you remove all the labels from your canned goods, prescription drugs, and cleaning products when you bring them home? Why don’t you give that a try?”

More pointedly, in my experience, the people who object the most vociferously to labels in politics tend to be people who are frustrated by the fact that the labels they object to make it harder to enact the policies they want.

Here’s how it typically works. Say you want to offer “free”—as in government-funded (i.e., taxpayer-funded)—housing to everyone. I call this idea “socialist.” You respond, “Oh, come on. Can’t we move beyond these tired labels? Just because you don’t like something doesn’t mean you can demonize it with words like ‘socialist.’”

My response: “You, sir, have it backwards. Just because something you like is socialist doesn’t mean I shouldn’t call it socialist, because that will make it less likely to happen, because socialism is unpopular. And by the way, you can call it ‘pragmatism’ or ‘social justice’ or ‘nationalism’ or ‘Cleophus the Seven-Eyed Dog.’ That won’t change the fact that what you’re talking about is socialism. Changing the name doesn’t change the reality. If you don’t believe me, drink this glass of ‘lemonade’ I just scooped out of the toilet.”

I want to be very clear: I haven’t changed my mind about all of that. Still, I have a question: What’s the value in calling things right-wing or left-wing today?

I have my own answers, but let me talk about why I ask the question.

In search of things to write about, I was reading Nellie Bowles’ always-fun Friday newsletter and came across an announcement from Jeremy Boreing, the co-founder of The Daily Wire. Boreing told the hosts at the Triggernometry podcast that Tucker Carlson is different than Candace Owens, because Owens is in effect an empty vessel ideologically and intellectually. These are my words, but that’s the gist. Owens is just an avatar for audience capture. But Carlson is different, Boreing said:

Tucker Carlson is part of a small cohort of people, cohort includes Marjorie Taylor Greene, cohort includes Steve Bannon, cohort includes Nick Fuentes—although I’m not saying that Nick Fuentes and Tucker Carlson believe all of the same things. But these are people engaged in an actual political project. These are people who are engaged in trying to create a new American majority, premised on left-wing economic populism and right-wing social populism. You can say what you want about that, whether it’s good or bad, you can say what you want about it, but it is a political enterprise. They believe that they can create a majority, and that that majority can rule the country, and it’s a new vision in terms of the ruling class in our country. It’s not that there’s never been people who put forward that vision, but it’s never been as poised to seize actual political power as it is right now in the hands of that group of people.

Now, I think this is interesting, and it’s worth taking Boreing seriously. I also think it’s wrong or misleading in important ways. But the fact that he thinks it’s true is significant all by itself. So: Boreing is broadly right that Carlson, Fuentes, Bannon, and Marjorie Taylor Greene are “engaged in an actual political project.” It’s been reported that Bannon wants to run for president in 2028 in order to build a movement (and, I’m told by some who know him, to pay his bills). Bannon is a left-winger on economics, full stop. He is a right-wing populist on cultural stuff. So right there is evidence in support of Boreing’s claim. Therefore, it’s certainly possible that they hope to “create a new American majority” based on a fusion of left-wing economic populism and right-wing cultural populism.

Where I part company with Boreing is when he says this vision has never been as poised to seize actual power as it is right now. First of all, something very, very close to that vision held sway in this country under Woodrow Wilson and FDR (which is, I suspect, one reason R.R. Reno wants to rehabilitate Wilson). But that’s an academic debate for another time.

The likelihood of such a project succeeding is my real objection. In short: fat chance. I don’t for a moment think that the Misfit Toys Brigade has it in them to midwife into existence a new American majority that can be counted on to win elections and stay cohesive. It’s entirely possible this group can make some progress in that regard. But come on—Carlson, Greene, Bannon, and Fuentes are not a Mount Rushmore of political strategists and statesmen. I can get into the nitty-gritty if you like, but as political science I just think this is preposterous. The fact that Boreing thinks it isn’t preposterous is interesting and troubling, but I’m still not buying it.

But I should get to my point. If we’re reaching the stage where many of the most famous right-wingers in America are willing to fully embrace left-wing economics, how useful is the phrase “right-wing” anymore?

Almost 20 years ago, there was a fun debate in my world about “liberaltarianism,” an idea promoted by the brilliant, and all-around solid dude, Brink Lindsey. If memory serves, The New Republic screwed him by slapping the “liberaltarian” label on the essay that introduced his argument. (“Hey, let’s come up with a word less euphonious than “libertarian”!) Basically, the idea was that libertarians should join the ranks of “liberals,” i.e. progressives, because the left was more enlightened on social issues and foreign policy, and in the process the left should give up at least some of its commitments to economic planning and social engineering. My argument then, and now, is good luck with that. What makes the American left the American left is its commitment to directing the economy and reorganizing society to fit its moral or aesthetic vision of the good. Asking it to embrace laissez-faire economics would be like asking the Dalai Lama to take up investment banking.

Economics is like, you know, a really important part of politics. It’s the place where government policy and daily life intersect—at least most of the time. The central thrust of liberaltarianism was to ask sincere left-wing people to stop being left-wing on the issues many of them cared about the most. I’m not saying a liberaltarian worldview is impossible—Lindsey’s a liberaltarian (or was). So is, broadly speaking, my friend Cass Sunstein, and many so-called neo-liberals in Europe probably fit that description as well. I have no doubt many Dispatch readers come close to such views as well. That’s great. I don’t have any first-order objections to it as a set of ideological priors.

My only point in bringing this up is that if a left-winger agrees to becoming a free-market, limited-government person on economics, we should probably stop calling them a left-winger. Likewise, if a right-winger wants a new New Deal—as Bannon does—or if a right-winger embraces Elizabeth Warren’s economic agenda—as Trump, Vance, Carlson, et al. have done at various times—in the American context maybe right-wing doesn’t work very well as a label anymore.

And that brings us to right-wing social populism, as Boreing calls it. I definitely think it’s possible to grow a new American majority that attracts new factions by combining left-wing economic populism with right-wing cultural populism. You know why? Because that’s what Trump did, electorally. The white working class and, to a lesser extent, working-class black and Hispanic men have been moving rightward on cultural issues for a while. Unions are still the backbone of left-wing economics, but the rank and file of the heavy industrial unions have been fleeing the Democrats for a long time. (Public unions, especially the teachers unions, are still wholly in the Democratic column.) What helped attract them was Trump’s leftward lurch on economics, especially trade.

There are ideas that fuel right-wing populism that I think are not only defensible, but objectively correct, at least directionally. Making more room for religion, traditional values, being more family-friendly, celebrating America as a good nation, etc.—these are things I can get behind, even if I find some specific policies and rhetoric off-putting or worse.

But a big chunk of what passes for right-wing populism is explicitly identitarian. One of the things that still infuriates critics of my first book, even among the minority of critics who read it, was my claim that Nazism’s identitarianism was left-wing. I wouldn’t put it that way today. But I’m not willing to defenestrate the argument entirely either. I think identitarianism runs counter to the American creed. Picking winners and losers based upon accidents of birth, skin color, ethnicity, religion, etc., is fundamentally un-American. When I wrote Liberal Fascism in 2008, the left was defending identitarianism full stop. There were even academics who effectively wanted to revive the “one-drop rule” for purposes of hiring and other benefits. I think state-imposed discrimination based on race is wrong, regardless of the race that is benefiting. It might be more wrong when aimed at whites than at blacks, but that’s a different argument.

I get that this is kind of a meta point. But if you believe—and you may not—that directing resources and benefits to people based on their race, sex, etc., is left-wing, then wanting to do it for white people as, say, Nick Fuentes and Pat Buchanan have floated, either means that your belief is wrong, or that you have embraced a left-wing idea.

Think about it this way: I grew up believing that the left wanted to use the government to organize and direct the economy to a large degree. I think that idea is wrong. Now, we’re told that the right wants to do it too. That it wants to favor different interests and industries doesn’t change the fact that it has the same idea about the role of government. Either that means those right-wingers have joined the left (which means the left won the argument), or it means those right-wingers aren’t right-wingers on economics anymore. Now use the same logic about identitarianism.

I understand that at this level of abstraction, a lot of practical politics gets erased. There’s a real difference—morally, philosophically, and politically—between wanting to use the state to help white people versus using it to help black people. There’s a big difference between wanting to help “green industries” and wanting to help fossil fuel industries or industries that contributed to your campaigns. (But don’t fool yourself—Democratic environmental policy is as influenced by donations and rent-seeking from green companies and unions as Republican environmental policy is influenced by donations and rent-seeking from “traditional” industry.)

But in my politically homeless corner of the remnant, I have the luxury of standing outside the fishbowl on many issues. The tyranny of small differences is one of my favorite topics, but we don’t have time to get into all of that. I bring it up just to illustrate a point. If you’re not a Muslim, the theological differences between Shia and Sunni are very difficult to really understand. Don’t even get me started on the differences between the Oriental Orthodox Churches and the Eastern Orthodox Churches, or the People’s Front of Judea and the Judean People’s Front.

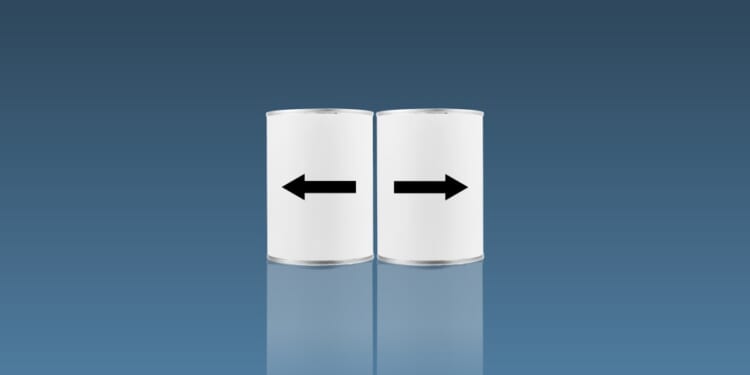

The point isn’t to say the differences aren’t important to the people involved or in some larger sense. But when I hear a lot of political arguments today that are supposed to be about great issues of high principle and truly conflicting visions, I see a lot of violent agreement between warring sides about means and a lot of low-principle disagreements about ends. And when you try to sort out what’s really going on, “right” and “left” just seem like different labels for very similar products.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Various & Sundry

Canine Update

As Bart Simpson said of Old Faithful, this weather both sucks and blows. The snow piled up and then was treated with sleet and freezing rain and arctic temperatures to form very pretty, but very treacherous, liquid concrete. The dogs do not like it because they slide and trip on it. In some cases, the surface is so hard that the normally exciting laser-melting effect of peeing isn’t even possible. The dogs were also very angry with me for being gone so long, almost as angry as TFJ. Pippa is so turned off by the conditions—and the road salt that doesn’t melt ice but does sting spaniel paws—that she’s taken to doing her business right outside the house and then turning around. But Zoë still craves adventure, in part because she feels so much better. The one amazing thing is that she’d rather go outside with her raw post-op skin exposed to the elements than wear that humiliating sweater. We’ve pretty much given up making her wear it. The more worrisome news is about Gracie, who is losing more and more weight, drinking more and more water, and barking, sorry, meowing more and more unreasonable requests. Jessica and Lucy took her to the vet today, and we are waiting on blood tests. But we know already the problem is her kidneys. As long as she’s not in pain—and we don’t think she is—we want as much time with her around as possible. Chester, meanwhile, has decided to wait until later in the day to make his demands. I think it has to do with the sun warming up the ground he has to traverse.

Canine Update goes here.

The Dispawtch

Member name: Seth Mangold

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: I prize honesty over rhetoric. The Dispatch always gives me perspective.

Personal Details: I am a criminal defense attorney. I am also a dog dad of two remaining French bulldogs named Olive and Tofu. They miss their brother, Bean, who passed away on January 25, 2026. I broke the bank and got him the best treatment. I was supposed to pick him up Monday, but I received a call from the pet hospital Sunday night that Bean had a heart attack and could not be revived.

Pet’s Name: Bean aka “Mr. Butt” aka “Mr. Dude”

Pet’s Breed: French bulldog

Gotcha Story: Bean was born in Alabama and used to serve as a stud. He was neglected. A woman I know who breeds French bulldogs got him at age 2, and I bought him from her at age 3. He was unable to hear, had a horrendous time potty training, but he was still the sweetest, most gentle, and the best dog ever.

Pet’s Likes: Naps, treats, Dad.

Pet’s Dislikes: Rain, snow, cold, and heat.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: Bean was always there for me. I have attached a photo of him looking up from my ottoman. The photo has a story. I was preparing for trial on a very serious predatory sex case. I was stressed out of my mind and had Bean sitting next to me. I think he could sense my stress and gave me the gentlest kiss on the cheek. I instantly teared up, and felt love and comfort.

A Moment Someone (Wrongly) Accused Pet of Being Bad: No one ever said that. He rarely got scolded, he had no aggression, and had limited curiosity. He loved everyone and presented himself for pets as soon as he met anyone.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Becoming a Dispatch member by clicking here.