Vipin Narang, the director of MIT’s Center for Nuclear Security Policy and former acting assistant secretary of defense for space policy, a portfolio that includes the U.S.’s strategic nuclear forces, told TMD that the constrained timeframe was perhaps the movie’s biggest factual flaw. “There would be no time pressure response in this scenario.” The U.S. would have more advance warning than is depicted here, and policy makers would not face imminent destruction, so could take time to determine who launched the missile and what their intentions were.

“The big takeaway people are going to have from this movie is that in the nuclear world, everything is on a hair trigger, and we’re going to just have minutes to make a decision about world-ending events.” Narang said. “And that’s just not true.”

The most controversial aspect of the movie revolves around the performance of ground-based interceptors (GBIs) launched from a base in Alaska, which twice fail to intercept the incoming intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). One character refers to the difficulty of bringing down an ICBM, which travels at up to 15,000 miles an hour, as “hitting a bullet with a bullet.”

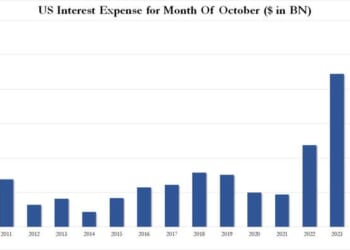

The U.S. currently deploys 44 GBIs, 40 in Alaska and four in California, which have cost $63 billion as of 2024, with a current budget request of $2.5 billion for 2025. In A House of Dynamite, after a character informs the secretary of defense that the probability of a successful interception is 61 percent, he exclaims, “So it’s a f—ing coin toss? That’s what $50 billion gets us?”

The Pentagon disagrees. An internal memo circulated earlier this month stated real-world capabilities “tell a vastly different story,” with recent tests having a nearly 100 percent success rate. But many experts noted that GBI test data comes from controlled experiments, rather than actual usage. While Narang called the 61 percent claim “probably right,” he noted that the U.S. would launch at least four interceptors (each with a 61 percent chance of hitting), rather than two, especially in the event of a single incoming ICBM.

An isolated, surprise nuclear attack on the U.S., then, is perhaps the least likely way that the first non-test atomic detonation since 1945 would occur. What’s more likely is the use of a smaller warhead. Caitlin Talmadge, a professor at MIT, pointed to the possibility of using a tactical nuclear weapon—a smaller-yield device designed for battlefield use (think blowing up an armored division rather than a city).

Russia seriously considered using such a device in October 2022. With the Ukrainian military pushing back Russian forces, Vladimir Putin and other officials began publicly claiming—without evidence—that Ukraine was planning to use a “dirty bomb,” essentially a conventional bomb loaded with radioactive material and intended to spread fallout, in an apparent pretext for the planned use of tactical nuclear weapons. President Joe Biden said that Putin was “not joking … about the potential use of tactical nuclear weapons,” and U.S. officials planned for the possibility of a Russian strike.

Russia has also moved to upgrade its infrastructure for tactical nuclear weapons in recent years, building airbases that give it the capability to launch strikes from Belarus, and on Sunday, Putin announced the successful test of the Burevestnik missile. It’s a cruise missile, powered by a nuclear engine, that would have a longer range than ICBMs and could theoretically reach any target on Earth. On Wednesday, Russia claimed that Poseidon, a nuclear-powered underwater drone that can carry a nuclear warhead, also had a successful test.

Pavel Podvig, a senior researcher at the U.N. Institute for Disarmament Research, told TMD that those tests, coupled with a probable briefing on China’s nuclear capabilities, likely prompted Trump’s post about atomic tests. “I can imagine that he felt like he needed to have some kind of strong statement and do something,” Podvig said, while noting that an actual resumption of nuclear tests would be extremely unlikely. On Thursday night, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said that Russia had not tested nuclear weapons, but would do so if the U.S. did.

Amid Russian provocations, some on the left are calling for a renewed focus on reducing the number of nuclear weapons. Sen. Ed Markey, a Democrat from Massachusetts, wrote in a Monday op-ed that A House of Dynamite showed that the“only nuclear defense worth believing in is disarmament,” calling for a renewed commitment to the New START treaty, the last remaining arms-control agreement between the U.S. and Russia, which expires in 2026.

But reducing warhead numbers, as President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev so famously did in the 1980s, may not be the most important goal.

“I would argue that the decreases in the arsenals were a follow-on effect of the sea change in political relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union,” Talmadge told TMD. While total stockpiles never dropped below Armageddon levels, reducing their number demonstrated that both leaders sought to avoid their use. It also saved both countries billions of dollars.

Commitments to regular diplomatic meetings, or systems like the “hotline” between the White House and the Kremlin (really a computer screen), are far more effective at actually reducing nuclear risk, Talmadge argued. No such hotline currently exists between the U.S. and China.

Developing personal relationships can also be important. Jon Wolfsthal, the director of global risk at the Federation of American Scientists and former senior director of arms control and nonproliferation at the National Security Council, told TMD, “Deterrence requires you to understand what your adversaries care about and how to influence their thinking.”

One of the fiercest debates among nuclear strategists regarding deterrence is the relative importance of preventive military measures: tracking submarines, monitoring the locations of missile silos and mobile launchers, and attempting to infiltrate security systems. Figures like Parang argue that the U.S. can credibly threaten to take out enough of an adversary’s launch capabilities to deter an attack, or at least mitigate enough of the damage that the U.S. is still standing at the end of a nuclear exchange. “That has been our strategy for decades, and we’re pretty good at it, and we don’t need nuclear weapons to do a lot of it,” he said.

Other policymakers disagree, saying that destroying enough missiles in advance of an exchange is too daunting a task. “We can accept mutual vulnerability, or we get an arms race,” Wolfsthal said. In this view, threatening the safety of adversaries’ nuclear forces makes them more inclined to engage in risky behavior, convinced that time is not on their side.

Artificial intelligence amplifies this double-edged dynamic. Sam Winter-Levy, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told TMD that AI could potentially make tracking other states’ nuclear weapons easier by analyzing massive amounts of data and upgrading cyber-warfare capabilities. If China and Russia “feel more insecure about their ability to threaten mutually assured destruction,” he said, they might be convinced that time is not on their side, and that they need to take aggressive action.

But then there’s the challenge of preventing non-nuclear countries from developing the bomb. Placing other countries under the U.S.’s nuclear umbrella, Talmadge argued, has stopped states like South Korea, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and Poland from developing their own nuclear weapons programs. Modernizing U.S. nuclear weapons—such as developing new sea-launched missiles—might be the best way to prevent a multi-nation arms race. “The United States wants to have some other bumps on the escalation ladder besides launching strategic nuclear missiles from the continental United States,” she said.

Wolfsthal argued that assuring U.S. allies of our commitment is primarily a problem of diplomacy. “You can’t solve a credibility problem with a capabilities solution,” he argued, pointing to the Trump administration’s well-known desire to avoid shouldering Europeans’ security burden.

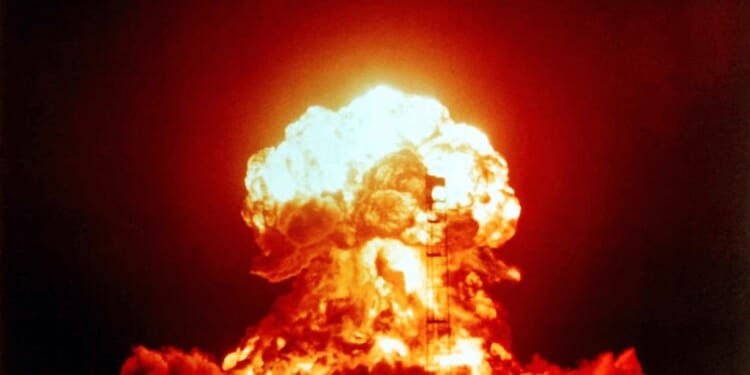

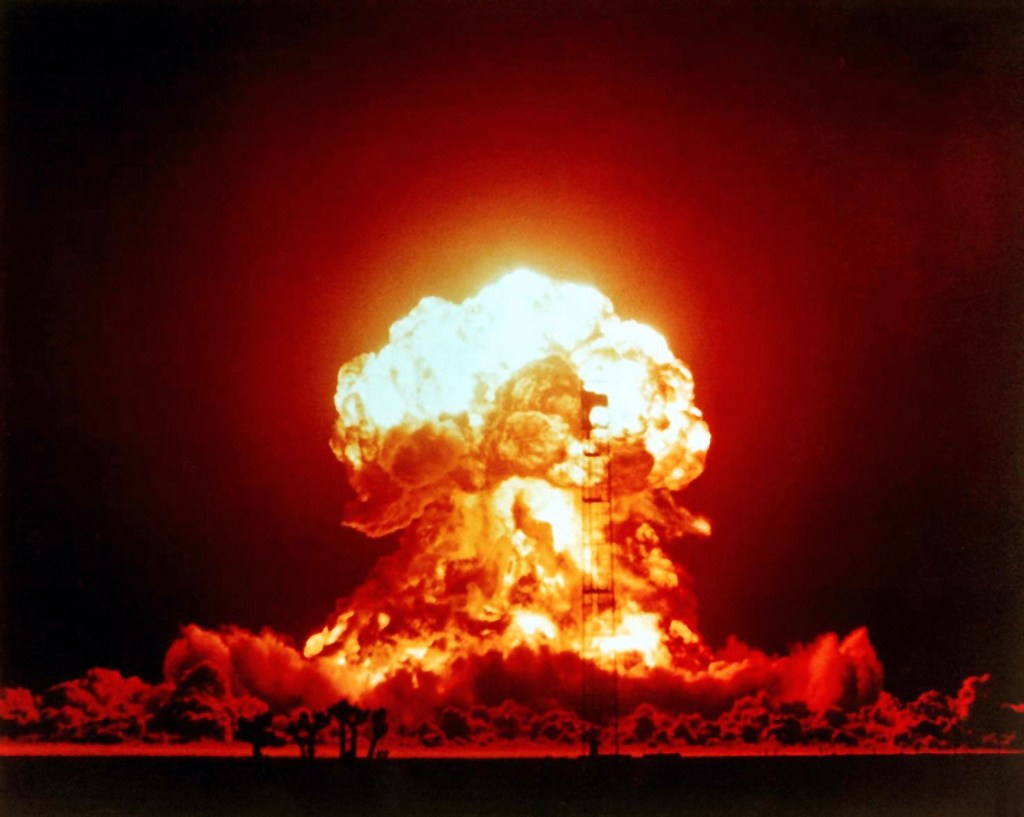

But Bigelow’s film isn’t concerned with restoring U.S. credibility or probing the fine points of how B-2 bombers operate. “It’s grappling with the idea that we’re surrounded by 12,000 [nuclear] weapons,” the filmmaker said Tuesday. “We live in a really combustible environment, hence the title.”

Or, as President Barack Obama once put it at the beginning of a National Security Council meeting on nuclear policy, “Let’s stipulate that this is all insane.”