You’re reading Dispatch Faith, our weekly newsletter exploring the biggest stories in religion and faith. To unlock all of our stories, podcasts, and community benefits—as well as our newest feature, Dispatch Voiced, which allows you to listen to our written stories in your own podcast feed—join The Dispatch as a paying member.

With a small number of notable exceptions, Dispatch Faith hasn’t been a newsletter for immediate reaction to the deaths of well-known figures. And at first glance, the death this week of Scott Adams, the controversial creator of the much-beloved Dilbert comic strip, may not seem like it warrants an immediate take either.

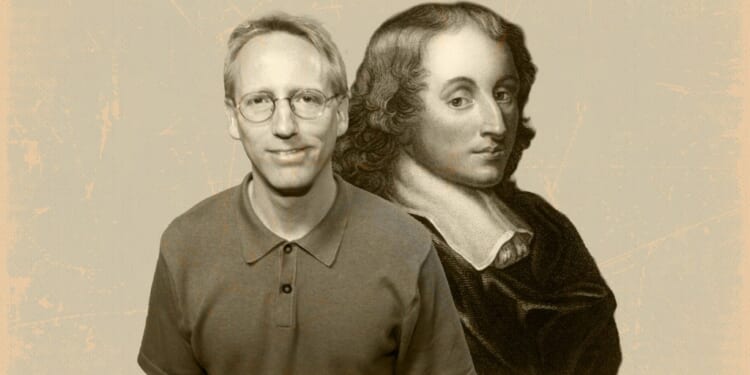

In Adams’ last message to his fans, read by his ex-wife after his death, he admitted the “risk-reward” element of Christian faith had convinced him to accept Christ’s sacrifice as personally salvific. As retired journalist Max Heine writes in this week’s essay, Adams was taking up what’s come to be known as Pascal’s wager, the argument advanced by 17th century genius mathematician Blaise Pascal—and in doing so has brought the debate about true belief to the fore once again.

You might’ve read about the January 13 death of Dilbert comic strip creator Scott Adams. Less publicized was the lead-up to his final weeks, following last year’s diagnosis of terminal prostate cancer, when he announced, with an intriguing angle, his planned conversion to Christianity.

In a January 4 livestream on X, Adams spoke in part to his Christian friends. Some had talked with him about being prepared for what happens after his impending death. “I’m now convinced that the risk-reward is completely smart. If it turns out that there’s nothing there, I’ve lost nothing, but I’ve respected your wishes, and I like doing that. If it turns out there is something there, and the Christian model is the closest to it, I win.”

I found no public record showing Adams was aware of the term “Pascal’s wager,” but that’s precisely what he was describing. The wager argues that in light of eternity, choosing to believe in God is the only wise choice. It’s attributed to Blaise Pascal, a genius-level French mathematician, scientist, and philosopher who jotted his musings on hundreds of pieces of paper. Some were scraps stuffed in his coat pockets. Some contained just one sentence. After his death in 1662, they were published in 1670 as Pensées (French for thoughts). Its religious content is consonant with Pascal’s Catholicism, though he was also influenced by Jansenism, a Catholic reform movement with Protestant leanings.

The wager has turned out to be red meat for opinionated philosophers, theologians, and anyone who relishes decision theory, game theory, certainty/uncertainty problems, etc. If you bet correctly that God and an afterlife are hokum, you gain whatever self-centered pleasures you find on earth, and you lose nothing after dying. But if your bet is wrong, you trade an attractive eternity with God for an eternity hotter than August in Death Valley. Conversely, a correct bet for God generally leads to a life well-lived, even with its sacrifices. The eternal payoff is huge.

Have you tried Dispatch Voiced?

Our newest members-only feature makes it easy to listen to our journalism on the go. Listen to high-quality audio versions of our biggest stories in your podcast player of choice, and catch up while grocery shopping, commuting to the office, running at the gym, or walking the dog.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Adams hoped to “win,” just as he had already in the worldly arena. In his early career, he worked at Crocker National Bank before joining Pacific Bell as an engineer. Drawing on the annoyances of those white collar jobs, he launched Dilbert in 1989 and it took off. Through the mild-mannered Dilbert and his stereotypical office colleagues, the comic strip lampooned boring meetings, clueless bosses, and absurd bureaucracy. At its peak, it had a worldwide readership of 150 million. The Dilbert franchise grew to include more than 60 books, themed merchandise, and an animated TV series.

Adams took advantage of his independence, growing celebrity, and, since 2018, his podcast Real Coffee with Scott Adams to air some fringe beliefs. Hollywood Reporter summarizes: “Over the years, Adams had disputed the death toll of the Holocaust, said ISIS supported Hillary Clinton for president, celebrated those who resisted getting the COVID-19 vaccine, reasoned that society looks upon women in the same way it does children and the intellectually disabled and introduced a Black character to Dilbert to poke fun at DEI in the workplace.”

Come 2023, Adams went too far. During a YouTube livestream discussion of a poll regarding race matters, he referred to black Americans as a “hate group” and made other disparaging remarks. Hundreds of newspapers dropped his strip. Its distributor did the same. (Adams later launched “Dilbert Reborn” as a paid online subscription.)

On his website, he said his race-related comments stemmed from his criticism of widespread DEI. “I recommended staying away from any group of Americans that identifies your group as the bad guys, because that puts a target on your back,” he wrote. Like many DEI opponents, Adams was a vocal supporter of Donald Trump since his first presidential campaign. He visited Trump at the White House in 2020.

As for spiritual beliefs, Adams was agnostic until recent months. He said details of any possible conversion were “between me and Jesus,” and he did not publicly address the most obvious challenge to Pascal’s wager: If someone chooses to profess Christianity for self-serving reasons, does that qualify as salvation in God’s eyes?

That’s sometimes called the “argument from inauthentic belief,” a common criticism of the wager. A second criticism of Pascal’s argument is its “failure to prove the existence of God.” Pascal had been working toward a Christian apology, but never finished it. Pensées, even with its breadth, did not purport to be an apology. Quite to the contrary of this criticism, Pascal argued that it’s impossible to prove or disprove God’s existence. Those deprived of any evidence of the divine but lacking the conviction gifted by grace to certain believers, Pascal wrote, should consider the wager’s logic as a starting point to escape their stalemate.

The third criticism is “argument from inconsistent revelations.” It says history’s many religions and gods deserve to be included in the wager. This would increase the chance of the bettor choosing the wrong god, significantly lessening the chance of the wager’s success. Pascal considered this argument a “trap” for a seeker looking to escape the wager’s dire reckoning, or so intellectually lazy he can manage only “a superficial reflection.” A spiritually hungry seeker would eventually discern that Christianity offers the only true path to God.

Going back to inauthentic belief, critics have said it’s stupid to think that an omniscient God wouldn’t see through even an Oscar-worthy performance of belief. Willliam James, author, psychologist and philosopher, wrote that a conversion based on “such a mechanical calculation would lack the inner soul of faith’s reality.” If one of us were God, “we should probably take particular pleasure in cutting off believers of this pattern from their infinite reward.”

But one problem with this criticism is in assuming beliefs manifest only in extremes. What about the in-between? Whether it’s an unbeliever considering commitment to any faith, or a longtime believer experiencing disillusionment, who wouldn’t devote at least some thought to missing the one boat bound for the right side of eternity? I’ve considered that more than once, and long before ever hearing it codified as Pascal’s wager.

Some religious outlets, writing before and after Adams’ death, were generally approving of any conversion—even one on a deathbed, as the Adventist Review applauded. Others, such as the Catholic Answers website, had some kind words for Adams, but also highlighted his rationale as too calculating.

To its credit, Catholic Answers coverage was rare in explaining one crucial point: Pascal offered the wager “as an intellectual threshold, hoping to move the skeptic from calculation and decision toward ultimate encounter and personal conversion.” Neither pure reason nor forced belief could yield a sure knowledge of God, but the wager offered a step in that direction. “Learn from those who were once bound like you, and who now wager all their possessions,” Pascal wrote. “These are people who know the road you wish to follow, and who are cured of a disease of which you wish to be cured.” And: “Follow the way by which they began; by acting as if they believed, taking holy water, having masses said, etc.” Embracing such habits “will naturally make you believe.”

You could dismiss such advice as a precursor to our era’s “fake it till you make it” ideal. Pascal, however, wasn’t suggesting fakery, but more of an apprenticeship. Not performance and ceremony for their own sake, but investing time to develop godly habits and relationships that form something deeper. As for the salvation to complete that apprenticeship, both Catholics and Protestants would point to Scripture for the basics: Repent of sin. Accept Christ and his forgiveness. Love your neighbor as yourself. Love God.

For whatever reason, Adams delayed his conversion. This further limited what little time he had for the nurturing growth Pascal described. In that January 4 X post, only nine days before his death, Adams said, “So I still have time, but my understanding is you’re never too late.” His final message, read by his first wife after his death, confirmed his plans: “I accept Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior … I have to admit, the risk-reward calculation for doing so looks so attractive to me. So here I go.”

I’ve concluded that there’s limited value in pondering all the nuances of wager logic and uncertainty. That’s because there are simpler ways to think about the subject and, for me, they trump some of the criticisms. Here are three.

Most of the wager debate focuses on betting for God, the more active decision. Yet as Pascal wrote, the house entertains two bets, equally weighty: “You must wager; it is not optional.” Those who refuse to wager that God is real, and to live and believe accordingly, have taken the opposing bet. Consider it a passive choice if you like, but its day of settling remains actively unavoidable.

Second, the prospect of heaven and hell—the foundation of the wager—is one of the oldest and most effective carrot-and-stick pairings. Pascal, with his keen mind, simply framed the risks and rewards to clarify outcomes for those who hadn’t thought it through or were in denial.

Finally, there is more than one path leading to a faith commitment. It might be the period of discipleship championed by Pascal. It might be a sudden revelation, like Paul on the Damascus road. It might emerge from closely observing the lives of believers, or for that matter, unbelievers who tragically reject faith-based principles and reap what they sow.

Or the change might start with a focus on eternity, move to a shrewd wager, and end with sincerity. If that begins on the deathbed but with little time to develop, as with Adams, who are we to judge the outcome?

More Sunday Reads

- Theologian Miroslav Volf and poet Christian Wiman each have their own remarkable stories. Volf was born in Croatia, raised in Germany, and for decades has been a leading Christian thinker and writer. Wiman grew up in hardscrabble circumstances in Texas, became a renowned poet, and for more than two decades has battled an incurable form of cancer. Both teach at Yale University and have stewarded a deep friendship. For Christianity Today, Andrew Hendrixson writes about their friendship and the correspondence that forms the basis of their just-released book. “Wiman said these letters ‘came at a period of great urgency.’ He had been diagnosed at age 39 with a rare and incurable form of cancer called Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Twenty years later, as he began his correspondence with Volf, he ‘really was dying.’ He went on to say, ‘It was a literal godsend to me the way that this exchange happened.’ Cancer’s effects on Wiman’s body come in waves, quieting for a stretch of years then becoming acutely virulent,” Hendrixson writes. “He was wrestling at the time with ‘what it means to love God.’ He said, ‘It seems to me such an abstract question. And in a way I feel like I know what it means, in the way that I feel like I know when a poem is beginning. It’s about the same sort of feeling. But there’s something very elusive and frustrating about it when you are in a period of suffering.’ ‘I found it immensely helpful to think about these issues with somebody concrete before me,’ Volf said of their email correspondence. Rather than working through an issue alone and ‘speaking to myself or to a potential reader,’ he said, ‘I had specifically Chris in view, and that just catalyzed something for me.’”

- For Tablet, Michael Doran has a long essay on how figures like Tucker Carlson betray America’s historical treatment of Jews. In framing the piece, he writes: “To explain the mystery of Jewish survival, European observers have repeatedly reached for supernatural causes. Their accounts tend to fall into two camps. The first interprets Jewish endurance as demonic. Its most influential exponent was Martin Luther, who insisted that ‘the devil … has taken possession of this people,’ leading them to worship not God but ‘their gifts, their deeds, their works.’ Accusing them of usury, deception, and moral corruption, Luther concluded that ‘no heathen has done such things and none would do so except the Devil himself and those whom he possesses, like he possesses the Jews.’ The second camp retained the supernatural frame but reversed its moral valence. Instead of demonic possession, it discerned divine design. St. Augustine argued that the continued existence of the Jews after their defeat by Rome served a specific function within Christian history. God preserved the Jewish people so that they might remain living custodians of the Scriptures, whose antiquity and integrity underwrote Christian claims about prophecy and fulfillment. … America rejected Europe’s supernatural framework altogether. The Puritans identified with the Israelites of the Hebrew Bible and saw America as a second Promised Land. They did not treat the Jews as cursed enemies. The covenant they imagined was shared, not hierarchical. Meanwhile, the Enlightenment had stripped Jewish survival of theological mystery altogether, grounding civic life in the equality of individuals before the law. From its founding, the United States absorbed Jews into public life as fellow citizens rather than symbols—neither demonic nor providential, but equal participants in a common political order.”

Religion in an Image