Today, the concept of “national security” is a staple of our political vocabulary, common in everyday language and entrenched in official institutions such as the National Security Council. But it was not always thus. Total Defense by Andrew Preston, a Canadian who is now a history professor at the University of Virginia after nearly 20 years on the faculty of Cambridge University, traces the rise of this concept and how it displaced earlier notions of national defense during the course of the 20th century. It is an important history, and one with underappreciated implications.

The book’s subtitle—The New Deal and the Invention of National Security—distills its thesis: the concept of national security as we know it today (involving military and foreign policy matters not limited to territorial defense) coalesced during the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. Before the New Deal era, “national security” was used relatively rarely, and often to refer to something more like economic and political stability or, in the 19th century, national unity versus sectional interests. But in the 20th century, a new vocabulary was required to grapple with increasingly grave foreign threats that did not involve the imminent invasion of U.S. territory. Such a vocabulary was largely lacking in World War I, but the term “national security” emerged in the years leading up to World War II.

Preston’s sometimes exaggerated language can occasionally suggest that this era’s national security policy was driven mainly by the New Deal’s internal logic, amounting to little more than another New Deal program. He describes the 1947 National Security Act (which created America’s modern security architecture including the Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, and CIA), for example, as “a New Deal for the world.” A more modest and probably more accurate reading, however, is simply that both Roosevelt’s national security policies and New Deal economic policies responded to similar developments, technological and social, and shared certain approaches and methodologies, such as frameworks of risk management and collective insurance as well as a high-modernist confidence in technocratic planning. On this point, the book is convincing. The policy framework for dealing with the world beyond America’s borders was “national security,” a counterpart to the overarching domestic policy objective, “social security.”

***

Preston is also adept at tracing subtle rhetorical shifts and locating their sources across a variety of policy domains and social currents. He shows, for instance, how Roosevelt’s national security rationale for the United Nations succeeded where Woodrow Wilson’s global-humanitarian arguments for the League of Nations had previously failed. The book makes a compelling case that the “invention” of national security shaped the strategies of the time and continues to influence policy today, often to our disadvantage. In pursuing “national security” we are, without knowing it, still viewing the world through a 1930s lens.

Unfortunately, Preston is often so attuned to the subjective experiences of the historical actors he portrays that he can lose sight of the objective conditions in which they operated. Indeed, he doesn’t really attempt to analyze the latter outside of his protagonists’ own statements and perceptions. Total Defense is the rare academic book that could benefit from additional factual detail and more theoretical context. Without any larger perspective to ground his analysis, Preston gets caught in some of the same confusions as his subjects. And while the historical material he surfaces is rich, the lessons he draws from it may not be the right ones.

***

America has always enjoyed a uniquely advantageous geographic position. As the overwhelming hegemon of its hemisphere, it has faced little risk of foreign invasion since the War of 1812. Until World War II, the United States was able to spend much less on its military than European and Asian powers, while still expanding across the continent. The greatest security risks throughout this period were internal, mainly the sectional divisions that culminated in the Civil War. Later, Preston observes, the United States also had to contend with large immigrant populations. Although the threat from treasonous “fifth columns” was minimal and often exaggerated, these diasporas occasionally sought to push the United States to intervene in old-world conflicts and invited foreign interference in U.S. policy, a problem that continues to the present. Nevertheless, for much of its history, America had little reason to concern itself with security matters beyond its territorial defense, which was not an especially difficult task.

Around the turn of the 20th century, however, industrialization began to disrupt these favorable assumptions. Military planners looked on warily as improving naval and military technologies shortened geographic distances. Preston recounts a number of apocalyptic books that appeared during this period, warning of imminent invasions that would overwhelm the feeble U.S. military, with foreign armies occupying broad swathes of the continent. These potboiler fantasies were overwrought, to be sure, but they reflected something real. Even basic territorial defense would require more resources than it had in the past.

At the same time, it became increasingly difficult to heed the warning against “foreign entanglements,” the most resonant part of President George Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address. Perhaps Americans could still avoid official diplomatic commitments, but the U.S. economy was by now deeply enmeshed in foreign supply chains, export markets, and financial networks. It was around this time that major banks such as J.P. Morgan began actively promoting an internationalist posture, and worked hand in glove with the U.S. and British governments on far-flung ventures across the globe, as chronicled in Ron Chernow’s classic House of Morgan (1990). A conspicuous flaw of Total Defense is that Preston spends far too little time on this latter point, which is key to his argument. Largely because America’s economic interests increasingly extended beyond the continental United States, a new vocabulary of national security became necessary.

***

These issues came to a head in World War I. As Preston tells it, President Woodrow Wilson himself was a reluctant convert to the interventionist foreign policies now called “Wilsonian.” Certainly, Progressive Republicans at the time were more bellicose, and Wilson campaigned on keeping the United States out of the war as late as 1916. Yet America ultimately could not countenance unrestricted submarine warfare, and the East Coast establishment feared the prospect of a defeated Britain and German domination of Europe.

According to Preston, however, Wilson struggled to articulate a compelling rationale for American intervention to a skeptical populace. The territory of the United States was not seriously threatened—the intrigues of the Zimmermann Telegram notwithstanding—and many Americans were uninterested in conflicts over sea lanes or international financial relationships. It was only due to the inadequacy of more conventional justifications, argues Preston, that Wilson eventually alighted upon “democracy” as his rallying cry: America needed to be involved in a global conflict to defend, not its territory, but its ideals. Thus, a new foreign policy doctrine was launched, though it swiftly ran aground when the Senate refused to ratify the treaty to join the League of Nations. Americans may have been willing to defend “democracy” in a crisis, but they were not ready to underwrite a permanent global security architecture for abstract humanitarian causes.

The underlying security challenges, however, remained. The American economy only became more thoroughly entangled in international markets and financial flows; military technology proceeded apace; and totalitarian ideologies with imperial ambitions were spreading across Europe. Whatever one thinks of the foreign policy debates before and after World War I, by the 1930s it became increasingly clear that the language of 19th-century American strategy simply left too many 20th-century problems unaddressed. A new intellectual framework, though probably inevitable, came from a surprising place.

***

Today, the domains of insurance and risk management do not seem especially inspiring sources of political rhetoric, but they were understandably appealing in the midst of the Great Depression. In fact, as Preston demonstrates, interest in these topics was largely bipartisan even if Roosevelt’s policy program was not. The Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, for instance, conceded that some basic social insurance could be necessary and even desirable. In 1921, University of Chicago economist Frank Knight, later an ardent opponent of the New Deal, authored a book titled Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit that laid the conceptual foundations of risk management, distinguishing between manageable “risk” and unknowable “uncertainty.” These principles received renewed attention after the calamity of the Depression. In a Burkean twist, the Keynesians often chided the neoclassical economists for being too confident in their mathematical models: because the world was more uncertain than economists thought, more insurance was necessary.

Following Ira Katznelson and other New Deal historians, Preston contends that this notion of risk management was the central premise of the New Deal. “Turning anarchic uncertainty into manageable risk…was the New Deal’s prime objective, because from there New Dealers could build a system to ensure security.” Further, “[e]ven though it was in some ways an odd value for a progressive to hold, as it could come at the expense of justice or liberty, this basic principle—security—was thus Roosevelt’s watchword.” Summarizing the arguments of other New Dealers, Preston concludes, “More than liberty, property, or prosperity, even more than democracy itself: security was the very foundation of the New Deal order because…everything else rested on it.”

As another world war threatened, then, it was only natural that this language of risk management and security was eventually applied to foreign policy. Preston locates the pivotal moment in Roosevelt’s “Quarantine Speech,” delivered in Chicago in 1937. Although the speech does not include the words “national security,” Roosevelt decried an “epidemic of world lawlessness” that needed to be quarantined. Because “we cannot insure ourselves against the disastrous effects of war,” he argued, the country needed to adopt positive measures to “minimize our risk.” After that speech, Preston observes, “Roosevelt repeatedly invoked the phrase ‘national security’ to explain America’s stakes in the world crisis, using it nearly as many times in those four years alone [1937-41] as all other presidents before him combined.”

***

From a term frequently used to refer to financial stability—Preston notes that in this era there was both a National Security Bank and a National Security Life and Accident Company—“national security” came to refer almost exclusively to foreign policy issues. The term captured risks that went beyond territorial defense, but did not rely entirely on Wilsonian idealism. As World War II progressed and was followed by the Cold War, the rhetoric and institutions of national security became entrenched. Roosevelt’s Democratic successors—Presidents Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson—all largely followed the same paradigm: expanded social security at home coupled with military interventions, in the name of national security, abroad. In fact, national security went global: today, countries as diverse as China, India, Israel, Norway, and many others all have national security councils.

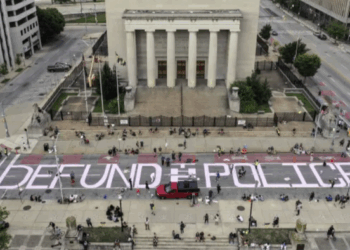

The concept is not without its pitfalls, however, which grew alongside the institutionalization of its vocabulary. First, the national security framing tends to narrow fundamental political issues into technocratic questions of risk management. As a result, national security would become the domain of experts and bureaucrats rather than democratic debate. This loss of democratic legitimacy would become a problem whenever the national security professionals erred, which seemed to happen with increasing frequency after World War II.

Relatedly, although the national security framework can allow for some debate on tactics, at least among experts, it does not really admit questions concerning ultimate ends. Once something is considered a national security priority, it is assumed to have some bearing, however indirectly, on basic survival—it is implicitly beyond debate. This creates a slippery slope.

To justify military action for purposes beyond immediate territorial defense, Roosevelt turned to the concept of national security. But its reach never stopped expanding. As one journalist put it in 1946, “There is no security except total security. There is no security except global security. There is no security for any nation that is not security for all.” Once the Cold War began, this maximalist logic became operationalized in the “domino theory”: “When any nation falls a victim to Soviet aggression,” said John Foster Dulles, Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state, “United States safety is lessened.” Therefore, the U.S. military must be prepared to intervene around the globe, even in conflicts with only the most tenuous connection to American interests, in order to provide an “insurance policy.”

***

Unfortunately, as one commentator noted, this theory began “eating its own tail.” It was a logic that underwrote decades of wars that did not end—and, by the logic of total security, perhaps could not end—in victory. For as U.S. national security commitments proliferated, so did America’s vulnerabilities. Preston recalls Undersecretary of State George Ball’s observation that “in pursuing containment in Southeast Asia to uphold US credibility for strength, [President] Johnson was undermining America’s credibility for good judgment.”

By the George W. Bush Administration, national security rationalizations had come completely off the rails and merged into a global neo-Wilsonianism. The security of the United States, Bush argued in his Second Inaugural, depended on the spread of freedom and democracy to all the world, by force of arms if necessary. “The American homeland,” according to The 9/11 Commission Report, “is the planet.” Such delusional overreach inevitably ended in monumental blunders.

Reaching the end of Total Defense, it is difficult to disagree with Preston’s conclusion: “The basic terms of national self-defense are long overdue for another reinvention.” His proposed redefinition, however, takes the same dubious logic to even greater extremes. Preston calls for refocusing national security away from defense and military matters and toward issues like climate change, or more broadly turning the New Deal risk management framework back to domestic social concerns. Yet, in light of the problems Preston’s history exposes, it is hard to see how further expanding the slippery and technocratic concept of national security to include an even more abstract and polarizing progressive policy wish list will lead to better outcomes.

On the other hand, Preston’s privileging of ideology over his own history does help explain why populist political movements in the last decade, and President Trump in particular, have provoked such intense resistance from national security insiders. In addition to any specific policy disagreements, Trump rejects the entire language of national security. He speaks in terms of “deals”—in essence, “what do we get out of it?”—rather than the framework of technocratic risk management to either economic or foreign policy. Although Trump, so far, has not been able to establish a new intellectual framework, as Roosevelt did, he nevertheless represents a profound challenge not just to individual policies and institutions but to the entire national security worldview.

***

Despite Total Defense’s many virtues, Preston devotes insufficient attention to the most fundamental questions. The underlying issue is not the shifting rhetoric of foreign policy, significant as that is, but American foreign policy’s inability to seriously confront the 20th century’s technological and economic changes. Like Wilsonian idealism before it, New Deal “national security” ultimately proved better at obscuring fundamental contradictions than resolving them.

Preston devotes an entire chapter to “the American way of life.” “The whole notion that there was a distinct American Way,” he writes, “emerged in the 1930s alongside the New Deal’s reform of government.” This notion fed into the concept of national security insofar as Roosevelt made securing the American way of life a key purpose of national defense. Preston quotes Roosevelt’s 1939 State of the Union Address, “There comes a time in the affairs of men when they must prepare to defend, not their homes alone, but the tenets of faith and humanity on which their churches, their governments and their very civilization are founded.”

Preston may be correct that the expression “the American way of life” was coined in the 1930s, but the idea it refers to is much older. The ancient Greek word for this concept is politeia, which is often translated as regime or constitution—not simply a legal document but the organizing institutions and animating principles of a political community. In other words, the idea that people would seek to defend their “way of life”—their churches, governments, and civilization—and not only a physical territory or biological population, was not an invention of the New Deal. A distinctive way of life, which a community seeks to defend from foreign enemies, is inherent to the concept of the political.

***

Moreover, the conditions believed to be required for the defense of the American way of life have remained remarkably consistent across different eras and governments. The first, of course, is territorial defense, understood from early on in continental terms, even before the United States extended across North America. The second might narrowly be defined as protecting America’s oceangoing commerce, which the U.S. military has defended against threats ranging from Barbary pirates to German submarines and beyond. Interpreted more broadly, however, these two principles coalesce into a specific vision of political and economic sovereignty. It seems central to the American character—not to mention the American Revolution—that the United States not be reduced to a resource colony or a dependency of another empire.

These criteria were easily satisfied prior to large-scale industrialization, when sheer distance across the oceans largely protected the fledgling republic from more powerful states. America simply had to avoid getting dragged into foreign conflicts, and a token standing army was all that was required to deal with the minor threats present in the Western Hemisphere. The militias could always be called up in a crisis.

But industrialization upended the modest foreign policy doctrines inherited from George Washington and John Quincy Adams. Beginning around the turn of the 20th century, upholding the foundational principles of American security would become much more difficult and require qualitatively different strategies than in the past.

In the first place, staying at the forefront of advanced military technology became increasingly important and required a permanent security apparatus. To take the most extreme example, maintaining a nuclear deterrent requires considerable resources as well as scientific and industrial expertise. Additionally, it is almost impossible for modern economies to avoid deep foreign entanglements, destabilizing imbalances, and relationships of dependency, whether formal or informal. Maintaining economic sovereignty in the industrial era simply requires a level of active stewardship and long-term strategy that was not previously necessary.

Indeed, a major indictment of the American national security paradigm, unmentioned in Total Defense, is that it proved wholly inadequate to dealing with these economic challenges in recent decades. The risk management emphasis on geopolitical “quarantine” and “containment” neglected the importance of geoeconomic developments. For decades, American “national security experts” were too fixated on “democracy” in the Middle East and Russia to notice that much of the U.S. industrial base was being offshored to China.

In any event, all countries, at some level, had to contend with the foreign policy ramifications of industrialization. These changes were perhaps felt more acutely in the United States, given the larger shift from its previous situation, but that was not the only problem. These transformations also penetrated to the depths of the American character.

***

Preston does not cite the political theorist and historian J.G.A. Pocock in Total Defense, but the latter’s work provides great insight into the issues under discussion. His most famous book, The Machiavellian Moment (1975), argued that America remained in key respects a Renaissance republic long after European nations became modern states. Critical to this republican orientation is the centrality of the militia and the independent citizen-soldier, which secured the republican “way of life” in military, material, and moral terms. Standing armies, on the other hand, represented an inherent threat to republican liberty. Thanks in no small part to its continental isolation, America was able to preserve its republican character deep into modernity, in some respects even to the present. Hence the advent of standing armies and complex economic interdependencies in the industrial era precipitated not just technical governance challenges but a political crisis.

In other words, the expansion of modern industry finally forced the United States to confront a dilemma other nations had faced much earlier: Americans could abandon their republican heritage and become a fully modern state—indeed, a modern empire—like their competitors. Or they could refuse the burden of a modern military along with the entanglements of a modern economy. Doing so, however, would result in a significant curtailment of their sovereignty, if not de facto subordination to a stronger empire. Either way, key elements of the American “way of life” would be in jeopardy.

This dilemma, a crisis that remains unresolved, is the essential context of Preston’s history. More than a century after these problems arose, Americans are still struggling to square the demands of the industrial world with their pre-industrial republicanism. Roosevelt’s national security framing functioned for a time, but only by obscuring the fundamental political choices behind the language of technocratic, global risk management.

From today’s perspective, the 20th-century national security framework combines the worst features of both American republicanism and technocracy. On the one hand, Franklin Roosevelt’s national security rhetoric did successfully mobilize republican energies to meet a crisis. Essentially, Roosevelt found a way to call up the militias in the absence of an immediate threat to U.S. territory by broadening the horizon of security risk: even if a problem does not look like an existential threat, it could easily become one without proper risk management. Unfortunately, national security logic’s lack of a limiting principle led to inflating every possible risk into an existential threat, a disposition augmented by the bureaucratic imperative to keep the national security state running.

On the other hand, the methodology of national security removes these supposedly existential issues from political contestation. Risk management is the domain of technocrats and experts, not citizens. Any solution to the failures of “national security,” then, will have to address both facets of this problem. It will have to allow for republican political contestation while being capacious enough to address modern realities.

***

Although it is impossible to go back to the simpler foreign policy situation of the pre-industrial era, we might still find some answers in an older terminology that avoids the perils of “national security.” In a new book on similar themes, The National Interest: Politics After Globalization, University College London associate professor of International Relations Philip Cunliffe calls for a rediscovery of the concept of “national interest.” Although Cunliffe does not directly engage with Total Defense, his book offers the most compelling response to the problems it raises.

Preston mentions national interest in his introduction—though never again—quoting one academic’s observation that the term “has almost completely dropped out of the vocabulary of students of international politics.” Yet there may now be an opportunity for a revival. As Cunliffe writes, “The fact that nations have been abandoned by the exhausted political traditions of the twentieth century means that [they] can now be reclaimed by the people,” opening a space for reconceiving national interests.

According to Preston, the difference between national interest and national security is the difference between discretion and necessity. “The national interest highlights what Americans want to do; national security mandates what they must do. National security is about survival and is therefore nonnegotiable, for without survival there is no national interest to pursue.” Stated another way, national interest includes security but goes beyond it; it is not purely defensive. “The national interest seeks something more discretionary: an advantageous position, improvements in conditions that facilitate basic security, a greater level of prosperity, or the promotion of values and norms.”

National interest therefore involves a debate over ends as well as means. It also allows for prudential considerations of competing goods in a way that national security does not. It may be beneficial, for instance, to reduce carbon emissions, but at what cost? It may be beneficial to intervene against a relatively hostile regime or on behalf of a relatively friendly regime in a distant conflict, but do the benefits outweigh the costs and risks? The logic of national security short-circuits such analysis; once something is designated a national security risk, actively managing that risk becomes nonnegotiable. Because promoting the national interest does not, by contrast, reduce every issue to a question of survival, it elicits political negotiation rather than technocratic risk management.

***

Yet recovering a sense of the national interest requires much more than repeating the words. For Cunliffe, reviving the national interest can occur only alongside the revitalization of the national political community. Whereas national security’s managerial abstractions treat the nation as a passive object, national interest requires its presence as a positive force.

Framing our problems as ones of national interest forces us to relate our problems to our fellow citizens…. In so doing, we will be collectively forced to break out of the political solipsism of the last thirty years, in which political community is either subnational (identity-based, ethnic) or supranational (religious, diasporic, human rights). Those political identities have shown themselves to be dead-ends.

Indeed, perhaps the greatest weakness of “national security” is that it failed to secure the nation as the locus of political identity. As competition with China intensifies, these debates over the language of national security are not merely academic. Preserving American economic and political sovereignty, even if not necessarily more difficult, is perhaps more complicated in the 21st century than it was in the 20th or 19th, and will require different approaches. An accurate understanding of America’s true interests will be needed to navigate these complexities and to orient its people. National security, in its most basic sense, may be prior to national interests. But the last several decades have shown that, without a positive vision of the nation, there is no national security.