Last week’s dramatic escalation in the conflict between Iran and Israel has dominated the headlines. It’s also likely to be at the top of the agenda as world leaders gather in Alberta, Canada, for the G7 summit this week. But leaders are also expected to discuss new sanctions on Russia, a priority for Ukraine’s supporters that threatens to set up a clash between Congress and President Donald Trump.

Legislation introduced in the Senate in April would represent one of the most aggressive U.S. moves against Russia in years and come at a time when Trump has shown a willingness to criticize Russian President Vladimir Putin.

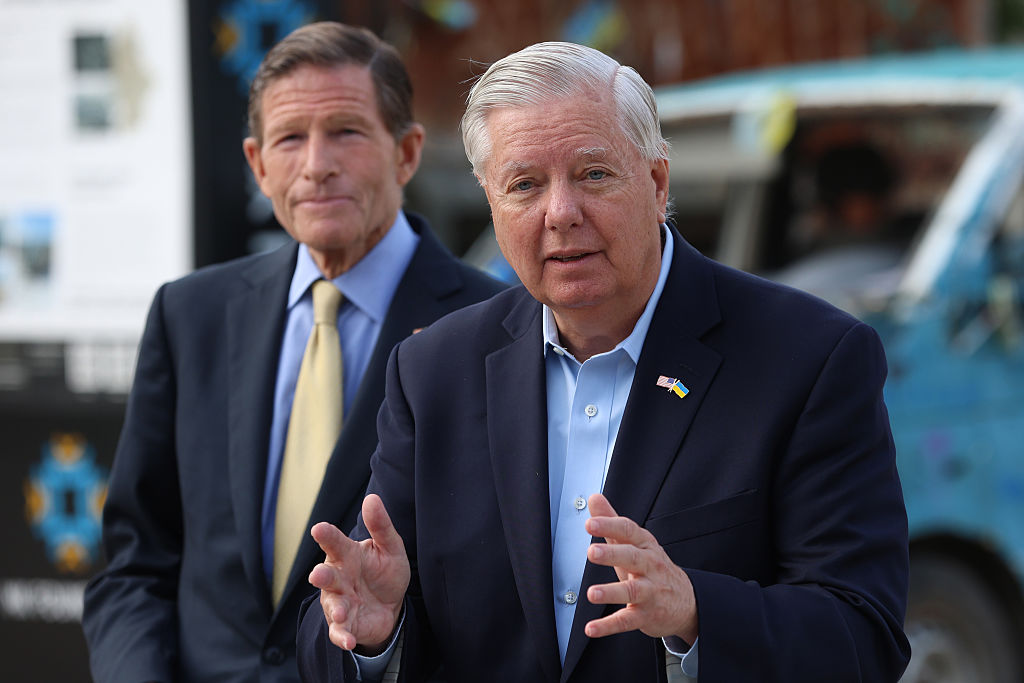

The Sanctioning Russia Act—introduced by Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut, and Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina—enjoys the support of 82 co-sponsors evenly split between the two parties, giving it a comfortably veto-proof majority in the Senate. But the White House has signaled that it may be unwilling to fully enforce the penalties contained in the bill, potentially setting up a major foreign policy clash between Congress and the president.

“Unfortunately, the more we engage Putin, the more aggressive he gets,” Graham wrote in a Thursday op-ed for Fox News’ website. “It’s time to change the game.” His bill outlines a significant scaling-up of sanctions on Russia: In addition to updating and intensifying a range of existing provisions targeting private individuals, companies, and financial institutions, it also potentially expands the U.S. sanctions regime to target those who do business with Moscow.

The legislation would seek to curb Russia’s fossil fuel exports by imposing a 500 percent tariff on any country that imports Russian oil and gas. The world’s third-largest oil producer, Russia relies on exporting natural gas and oil to maintain critical foreign currency reserves and fund its war machine. Roughly 30 percent of Russia’s federal revenue in 2024 came from energy exports, with China, the European Union, and India each purchasing hundreds of billions of dollars worth of energy over the last several years.

Europe, which is still reliant on Russia for much of its power generation, has sought to blunt Russia’s export efforts by imposing a price cap of $60 a barrel on Russian oil, but a recent slide in global prices to roughly $57 a barrel has rendered the cap largely meaningless. Additionally, Russia conducts a brisk trade with a variety of countries through its “ghost fleet,” hundreds of cargo ships that sail under obscured ownership to evade sanctions.

But some experts say that, as currently written, the sanctions targeting countries that trade with Russia are unworkable. The imposition of 500 percent tariffs on all countries importing any amount of Russian energy would be an even more extreme version of the “Liberation Day” tariffs announced by the White House in April, Edward Fishman, a former adviser to former Secretary of State John Kerry on economic sanctions and the author of Chokepoints: American Power in the Age of Economic Warfare, told The Dispatch.

“In this instance, this threat is not credible,” he said, pointing out that countries like India rely on Russia for a significant portion of their energy imports. “The likeliest outcome if this bill were to be passed and signed as written is that it would never be implemented.” For example, even after a years-long effort to reduce consumption, 19 percent of Europe’s gas demand is still filled by Russian imports, often delivered through third parties like Turkey.

This dynamic, however, is not unusual for sanctions bills. Often, Fishman noted, Congress begins with more severe demands as a starting point in negotiations over the exact shape of the legislation. But the strong support for the act shows that Congress is interested in moving faster than the White House on sanctions; Trump has not imposed new penalties on Russia since 2020.

Back-and-forth on the bill’s specifics between the White House and Congress has already begun, and Graham has already shown he is willing to make some significant modifications to the package. After multiple countries reached out to senators with concerns about the potential tariffs, for example, the Republican said the bill could include a carveout for countries that have provided military or economic support to Ukraine.

But despite the “bone-breaking” provisions touted by Graham, the bill still gives the White House some leeway. If the act passes, the president will have 15 days to determine whether Russia is refusing to engage in peace talks, undermining Ukraine, or ramping up its military assault. If the answer to any of those questions is yes, the president would be mandated to impose the full range of sanctions in the bill. The designation would then be revisited every 90 days, with the penalties only lifted if Russia stops the targeted activities and signs a peace deal with Ukraine.

Both Graham and Blumenthal have been at pains to portray their legislation as aligning with Trump’s priorities. “We have been working with the White House since day one in drafting this package,” Graham wrote on Thursday. “We’re very encouraged,” Blumenthal told The Dispatch’s Charles Hilu when asked about the status of negotiations between the Senate and the White House earlier this month. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, a Republican from Louisiana, has also said that he is an “advocate” of sanctioning Russia as strongly as possible.

Trump has also been more willing in recent weeks to speak out against Putin, whom he refrained from publicly criticizing for much of his first few months in office. Late last month, the president referred to Putin as “absolutely crazy” following Russian strikes on Ukrainian cities and said he would “absolutely” consider additional sanctions on Moscow.

But behind the scenes, things may not be going so smoothly. Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that administration officials have quietly urged Graham to add more flexibility to the bill by giving Trump the ability to grant waivers to individuals and entities who would be potentially targeted, along with replacing the word “shall” with “may” throughout the legislation, granting significantly more wiggle room in enforcement.

The administration’s strategy, at least publicly, is to demonstrate that it is focused on negotiation with Russia, rather than coercive measures. Appearing before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense on Wednesday, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pointedly refused to take a strong line against Russian aggression. “This president is committed to peace,” he said in response to a question from Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell about which side Hegseth wanted to prevail in the ongoing war. “Even if that outcome will not be preferable to many in this room and many in our country.”

Sen. Chris Coons, a Democrat from Connecticut, was even more specific, questioning Hegseth directly on the sanctions bill during the hearing. “Would you agree,” he asked, “that the U.S. should use every tool at its disposal, including additional sanctions, to pressure Russia to come to the table?” The secretary refused to endorse the sanctions package. “Every tool at our disposal? No. We have a lot of tools in a lot of places,” Hegseth answered.

On Thursday, Secretary of State Marco Rubio also demonstrated that the White House is still attempting to strike a conciliatory tone toward Russia. “The United States remains committed to supporting the Russian people as they continue to build on their aspirations for a brighter future,” he said in a statement marking Russia Day, the first time the U.S. has acknowledged the holiday since the start of Moscow’s invasion. “We also take this opportunity to reaffirm the United States’ desire for constructive engagement with the Russian Federation to bring about a durable peace between Russia and Ukraine.”

Trump, potentially the most important voice in the entire debate over the bill, has shown some trepidation about aggressively sanctioning Russia in recent days. When asked by reporters about the act last week, Trump demurred, saying he had not yet studied its provisions. “At the right time, I’ll do what I want to do,” he said. “It’s a harsh bill, very harsh.”

But the president will likely be forced to make his position clearer in the coming days. Last week, the European Commission proposed its own sanctions package, which would lower the price cap on Russian oil to $45 a barrel from $60. “We are very much aligned,” in seeking to bring the Kremlin to the negotiating table, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said of her conversations with Graham. Ukraine, whose leaders are in attendance at the G7, also plans to press Trump on sanctions in the coming days. “I count on having a conversation” with Trump at the summit, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said on Thursday.

For Ukraine, the need to get the U.S. on board with sanctions is urgent. In recent days, Russia has launched multiple massive air raids on cities and towns across Ukraine. It is also beginning a summer offensive, massing 50,000 troops in the northeastern province of Sumy and reportedly calling for “one last push” to end the war. Through multiple diplomatic meetings, Russia has also remained committed to conditions that Ukraine finds unacceptable, ranging from demands to annex territory it does not currently occupy and mandating limits on the size of Ukraine’s military.

More than 80 senators have signaled that they think Russia can only be swayed by further pressure. “We need to put Russia on an economic island, isolated from the world economy,” Blumenthal said last week. Time will tell if the president agrees.