Texas passed a big school-choice bill in April, but Texas Republicans first had to fight for years against their proposal’s most energetic and unmovable opponents: Texas Republicans.

It wasn’t the Texas teachers’ unions that led the fight against school choice in the state—their members do not much care for measures that expose them to competition and accountability, but their members also are prohibited from engaging in collective bargaining, or going on strike, or forcing teachers to join unions, so they do not have the kind of clout they have in, say, California. Also, the Democratic Party in Texas is kind of a basket case, driven mad by a generation in the wilderness and embittered by the recurrent mirages of such figures as Beto O’Rourke and Wendy Davis.

Rural Republicans have a lot more clout in Texas, though that is mainly a matter of political engineering and inertia rather than numbers: By rural population share, Texas is only a little more rural than Maryland (17 percent vs. 14.7 percent) or Washington state (16.6 percent) and a lot less rural than Virginia (24.9 percent) or Minnesota (28.9 percent), but there are a whole bunch of long-serving, influential legislators out there representing largely rural districts. The speaker of the Texas House serves a typical GOP district: He has a slice of Lubbock County (including my former home) and the entirety of 10 other counties that range in population from 631 to 16,932—the contemporary Republican model of lots of real estate and not a lot of people. In many of those counties with 6,000 or 7,000 people (and in a fair number of larger ones, too), the largest single employer is the public school district. And many of those rural communities do not have many—or any—private schools to which to take those new vouchers. If you are a rural cotton farmer married to a rural high-school principal, you probably get your insurance (and your retirement plan, and much else) from the school system. There is not much upside, for you and your family, to school choice.

Republicans in the Texas speaker’s district may talk a good fight when it comes to anti-government radicalism, but, as it turns out, the biggest city in the district is largely dependent on government spending (its economy is dominated by Texas Tech University) while the rural areas are even more dependent on farm subsidies. Texas farmers are the nation’s largest collective recipient of farm subsidies: Together with neighboring Kansas, Texas farmers receive 27 percent of all federal agriculture subsidies. My part of Texas is jam-packed with libertarians on welfare, attached to the public teat in one way or another.

Rural-suburban-urban politics are, as it turns out, much more complicated than many people assume. Republicans currently have a commanding position among rural voters, especially in presidential elections, but they do not have a monopoly: About 60 percent of rural voters pull the “R” lever, while more than a third go “D.” Rural voters are typically more dependent on government programs of various kinds—from farm subsidies to Medicare—than are the millionaire suburban car dealers who effectively run the Republican Party. The best jobs in many rural areas are government jobs: school administrators, municipal officials, etc. Historically, these people were Democrats: I grew up not far from the town of New Deal, Texas, and had a grandfather who would have made Steve Bannon look like Zohran Mamdani, but he considered every Republican walking the Earth his mortal enemy—going hungry in a farming community during the Great Depression left a partisan mark on him.

The Democratic Party apparently has hired Captain Obvious as a political consultant and has secured some good results for its side by—here’s a big idea!—running more moderate candidates in more moderate areas and running boutique radicals in New York City. Just as Donald Trump made inroads with African American voters and Hispanics by appealing to their interests and—another big idea!—actually bothering to ask them for their votes (the subsequent disappointment has been severe), relatively moderate Democrats such as Virginia Gov.-elect Abigail Spanberger have improved on their party’s position in farm country by campaigning there and talking about relevant local issues.

As Politico reports, Spanberger improved on Kamala Harris’ performance in almost every rural county in Virginia and—more relevant—ran 19 points ahead of Terry McAuliffe’s 2021 gubernatorial effort. That means that the Republican advantage in rural Virginia was cut from 27 points to only 8 points. Republicans were not going to make up those lost rural votes in the densely populated Washington suburbs of northern Virginia, where Spanberger won a commanding 72.3 percent of the vote. About 88 percent of Spanberger’s vote total came from suburban NoVa—the Democrats are very much the party of college-educated, affluent, young and young-ish professionals, especially government-adjacent ones—but a relatively strong position in the rural areas makes it pretty hard for Democrats to lose in a state such as Virginia. Spanberger did not put on overalls and campaign as a hayseed—she talked about market access, extension programs, and the state’s Agriculture and Forestry Industries Development Fund.

Rural Americans do not love tariffs, government shutdowns, or economic chaos—and 1 out of 4 Virginians lives in a rural area. Consider which states are similar in that way: Pennsylvania (23.6 percent rural), New Mexico (24.7 percent), Georgia (26.6 percent), Michigan (27.1 percent)—states that lately are in play in presidential elections and that most often go for the winning presidential candidate (8 of 10 for Pennsylvania, 7 of 10 for New Mexico, 7 of 10 for Georgia, 8 of 10 for Michigan, and a modest 6 of 10 for Virginia). As Barry Goldwater once put it in a less happy context: You want to hunt where the ducks are.

Democrats disappointed by their senators’ postelection compromise over the government shutdown insist that their party must be more radical, more confrontational, more Trumpy, more trollish, “ruthlessly pragmatic,” as Yasmin Radjy of progressive voter-turnout group Swing Left put told the Washington Post. But there is some question-begging in the formulation “ruthlessly pragmatic. Running angrier, more extreme campaigns, pushing ruthless procedural and legalistic maximalism limited only by the principle “that it is within the laws and constitutions of the state,” as Maryland Senate President Bill Ferguson puts it in the same report, might be a winning strategy—in Tribeca and Brooklyn, in Chicago, in Austin and San Antonio. But the Democrats already have those voters pretty well locked up: Democrats have been winning Austin and its county (Travis) by an average of 42 points for years. But Trump won big in some heavily Hispanic rural counties.

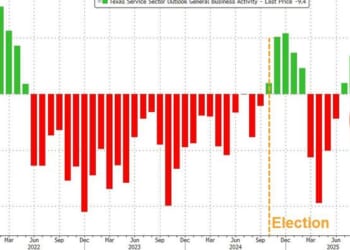

Rural voters may be disproportionately dependent on certain kinds of government services, and their families often depend on income and benefits associated with government employment, but they are not left-wing radicals either as a matter of policy preference or as a matter of temperament. Trump won Texas with only 52 percent in 2020, a showing slightly inferior to his 2016 performance in the state. Trump won Texas with a better showing in 2024 (56 percent), but not because the left-wing crazies in Austin were too stoned to make it to the polls: He increased his share in part because he improved on Republicans’ rural advantage, extending it into such largely Hispanic rural counties as Maverick and Starr. Trump did not run in those counties as a socialist talking about income redistribution and intersectionality: He ran as a guy bitching about high prices at the grocery store.

And Trump, being Trump, has repaid rural America for its support by screwing over America’s farmers with his imbecilic anti-trade policies and an undisciplined fiscal attitude that has helped to keep inflation abnormally high and, hence, interest rates higher than many had hoped or expected. There are votes there in the countryside to be had by those willing to fight for them—they probably should not send the incoming mayor of New York City to do the asking, but one would think that would be obvious enough even for Democrats.

It may very well be the case that ruthlessness is not, in fact, pragmatic—that ruthlessness contributes to polarization and to us-vs.-them tribalism that serves Democrats pretty well in places they are going to win, anyway, but costs them in places where they might find new allies. And if Democrats cannot find new allies while the Republican Party is operating as a full-time personality cult in the service of a retired game-show host and quondam pornographer who already has tried to stage one coup d’état and may very well try again—then even Captain Obvious won’t be able to save them.