Last week, Texas GOP legislators unveiled a new proposed map for the U.S. House districts in their state that could result in Republicans winning a handful of more House seats in 2026. The redistricting process typically plays out right after each decennial census, and the unusual mid-decade redistricting move by Republicans prompted Texas Democrats to flee the state in an attempt to deny GOP leaders a quorum necessary to conduct legislative business and thus block the new maps from becoming law.

So, what does this mean for Texas? How might blue states respond? And what does it all mean for the 2026 midterm elections and beyond?

To answer these questions, I turned to the Cook Political Report’s David Wasserman, an all-around expert on elections who has taken a keen interest in House races and redistricting over the years. His Twitter/X handle is @Redistrict for a reason.

What it means for Texas.

While many headlines have described the Texas plan as handing Republicans an extra five “safe” GOP seats, Wasserman thinks the range of GOP pickups under the new map in Texas could be anywhere from three to five. “Republicans are likelier to gain five than three, but there are two seats that are somewhat questionable in South Texas. Republicans weren’t maximally aggressive there,” Wasserman said in an interview.

Under the proposed plan, the South Texas district held by Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar would become 3 points more favorable toward Trump. But in 2024, Cuellar won his district by 5.6 points even as Trump carried the district by 7 points.

Another South Texas district, this one held by Democratic Rep. Vicente Gonzalez Jr., would be redistricted to become 5 points more favorable toward Trump. But Gonzalez won by 2.6 points in 2024 while Trump carried the district by 5 points.

“I think the jury’s out on whether the voters in that region gravitated towards Trump or whether they’ve begun to identify as Republicans,” Wasserman said of the districts held by Gonzalez and Cuellar. “Republicans have sought to slightly increase the number of Hispanic-majority districts by population, even while increasing the number of Republican seats.” He noted those seats remain Republican not just because of Hispanic movement toward the GOP but because of “how low the citizenship and voting rates are among the Hispanics in the [districts],” combined with high voter turnout among white voters.

Of course, Republicans’ picking up three to five House seats in Texas depends on the new maps actually becoming law, and Texas Democrats fled the state over the weekend to Illinois—a state that happens to have its own aggressively partisan gerrymandered congressional maps to benefit Democrats—to deny Republicans a quorum necessary to implement the map. But as the Texas Tribune reports, the Texas Democrats’ attempt to deny a quorum “represents the latest chapter for the maneuver that political scientists say, barring exceptional endurance on the part of the democratic delegation, is likely to be symbolic rather than directly effective in preventing redistricting.”

There is a November deadline for candidates to file for spring primary elections, but even if quorum-denying Democrats return after November, Republicans could still enact the new maps and order a second round of primary elections. And Texas Democrats will face pressure that is both political and personal to return home. “Many of them have children, families that they’ll be not seeing, at least not in state, missing things from football games to confirmations,” Mark P. Jones, a political science professor at Rice University, told the Tribune. “The precedent is that it’s not that hard to do for one [30-day] special session. It’s possible albeit a reach for a second. Going toward a third would be unprecedented.”

How blue states might respond.

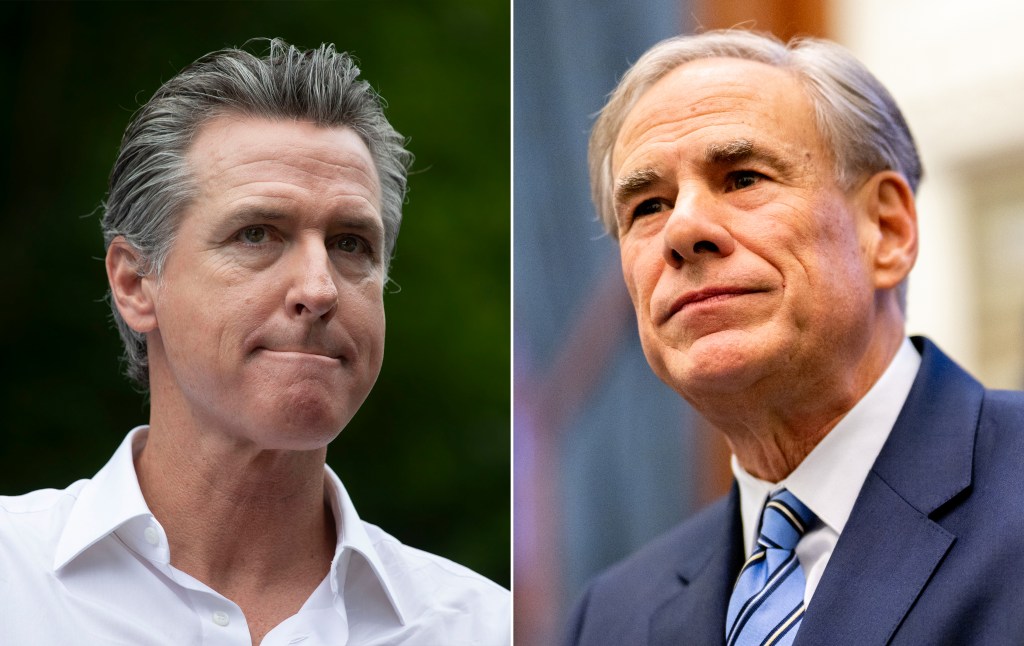

The redistricting push in Texas has prompted Democrats nationwide to call for their own aggressive efforts to redraw their maps, but they face several hurdles. The state with the most juice left to squeeze from an aggressively drawn partisan map is California, and Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom has vowed to do just that.

“Everything is at stake if we’re not successful next year in taking back the House of Representatives,” Newsom said recently, warning that such a failure could literally mean the end of American democracy. “They’re not screwing around. We can’t afford to screw around either. We have got to fight fire with fire.”

But there is a serious obstacle for Newsom and California Democrats to overcome: A 2010 proposition that voters passed 61 percent to 39 percent established a bipartisan commission for drawing congressional maps. That means California Democrats would need a new referendum to hand power to the Legislature and Newsom to redraw the maps.

Can California Democrats do it—and get it done in time for the 2026 elections? Wasserman thinks it’s possible. “They could seek a ballot initiative that is marketed as anti-Trump, even if it tramples the very reform that voters passed by a large margin in 2010,” he said. California’s delegation in the U.S. House of Representatives is currently split between 43 Democrats and nine Republicans, but Wasserman thinks if the Democratic state legislature redraws the maps, it would be possible to limit Republicans to four or five seats in California. The incumbent House Republicans most endangered by such a plan, he said, would be Young Kim, Ken Calvert, Kevin Kiley, and David Valadao.

Beyond California, there are legal and political obstacles for blue states to add more Democratic seats via redistricting.

After California, New York is the next most populous blue state, but “Democrats already sought to revisit the map in advance of last cycle, and were not really able to to stretch their advantage much more,” Wasserman said. “Now, theoretically, it’s possible for them to do so, but under New York’s constitution, unlike Texas, there are anti-gerrymandering provisions. … Democrats are leery of the state supreme court invalidating a map that is too aggressive.”

The main problem for Democrats in blue states where the legislature entirely controls the redistricting process is that they’ve already maximized their partisan advantage via gerrymandering. “Democrats have a 9-0 advantage in Massachusetts, they’re 14-3 in Illinois,” Wasserman said. “Democrats would have to neuter the New Jersey commission to squeeze more seats out of that state. They are 3-0 in New Mexico; 5-1 in Oregon.”

Republicans, meanwhile, still have some redistricting cards to play.

Ohio has a constitutional amendment that says if the Legislature can’t reach a bipartisan decision on congressional maps, a commission makes the decision. Republicans currently hold a majority on that commission, and that could mean an extra two seats for Republicans.

In Missouri, the GOP-controlled Legislature has the ability to turn a 6-2 GOP U.S. House map into a 7-1 map—something they’ve been reluctant to do so far, Wasserman said, due to traditionalists in the state capital “who do not want to upset the apple cart of the seats surrounding Kansas City and Republican incumbents surrounding Kansas City that don’t want to take on more Democrats.”

What it means for 2026 and beyond.

How exactly redistricting might play out nationwide in 2026 and beyond remains unclear.

One of the remarkable political developments of the Trump era is that Republicans no longer have a big structural advantage in House races. The old Republican coalition used to be much more efficient in winning purple suburban districts, and that’s a big reason House Republicans were able to hold onto their majority in 2012 even as President Barack Obama won the national popular vote by 4 points. But the new populist GOP under Trump is weaker in the suburbs and stronger in rural districts and urban districts. The problem for Republicans is that there’s no advantage in the U.S. House for running up the score in red rural districts or losing by a smaller margin in blue urban districts.

In 2024, there was actually a slight Democratic tilt to House districts nationwide. As elections analyst Sean Trende noted, House GOP candidates nationwide got 51.3 percent of votes in House races but ended up controlling 50.5 percent of House seats, and Texas’ addition of five seats for Republicans “would make things roughly proportional” between the national popular vote corresponding to the breakdown of U.S. House seats.

That means Democrats still have good odds for taking back control of the House. Midterm elections are often correlated to the incumbent president’s job approval rating. Back in 2018—the midterm election of Trump’s first term—Democrats took back the House majority with 235 seats to 199 for Republicans. At a time when the incumbent GOP president’s approval rating was clocking in at 38 percent, Democratic House candidates nationwide won 53.4 percent of all votes while House GOP candidates won 44.8 percent.

“If Trump’s approval is in the 30s [in November 2026], then Democrats are probably the favorites to retake the majority, regardless of what Texas or Ohio does,” said Wasserman. “But if it’s in the low 40s, then Republicans do have a chance to defend their majority, given this gerrymandering.”

In the latest Gallup poll, Trump’s approval rating hit a second-term low of 37 percent, and the latest Reuters survey found Trump’s approval rating at 40 percent. But a July poll from YouGov/The Economist found Trump’s approval rating at 44 percent, and Emerson pegged it at 46 percent. Where it will be when the midterm elections are held 15 months from now is anyone’s guess.

But there does seem to be a clearer sign of where the process of partisan redistricting is ultimately heading. “The logical end point of this arms race,” Wasserman said, “would seem to be the eradication of blue-state Republicans and red-state Democrats.”