Anybody who spends much time on social media, especially that website formerly known as Twitter, has likely seen an uptick in antisemitism these last couple years. As a Catholic, it has been disappointing to see so much of it among Catholic youth. For many years, we lived in a world in which the social memory of the Holocaust was tangible, when the “ick” toward antisemitism was nearly universal.

But in the last couple years, especially with Gen Z’s inclination to blame Israel for its handling of the war in Gaza, that memory and that social immunity has, to some degree, shown signs of wearing off. Now, one can find popular Catholic accounts on social media, or young zealous Catholics on college campuses, who have rediscovered and uncritically embraced some of the antisemitism that was so popular before and during World War II. In light of this, it is critical that Catholics learn from the shameful mistakes of the past and embrace the efforts of the Second Vatican Council to correct this problem.

If you call these young antisemites out, they are likely to say something like “I don’t hate Jews … it is just that powerful Jews are conspiring to harm civilization.” Call this the “I don’t hate Jews” defense, and if it is said in earnest, it reflects a misunderstanding of what antisemitism usually looks like. Nick Fuentes recently used this defense when responding to Tucker Carlson’s claim that Fuentes is an antisemite (pot-kettle, I know), stating, “I’m not a Jew hater. I don’t hate anybody. I just recognize, like everybody does now, that we live in a Jewish oligarchy.”

Fuentes’ comment is representative of modern antisemitism. It does not typically manifest as explicit hatred of Jews, nor is it usually based on a racial theory, as it was in Nazism. A more typical form of antisemitism was that popular among 19th and early 20th-century reactionary Frenchmen (e.g. Louis Veuillot and Charles Maurras). This antisemitism involved the scapegoating of Jews for societal ills or political upheaval and often the use, and credulous acceptance, of conspiracy theories to rationalize and justify that scapegoating.

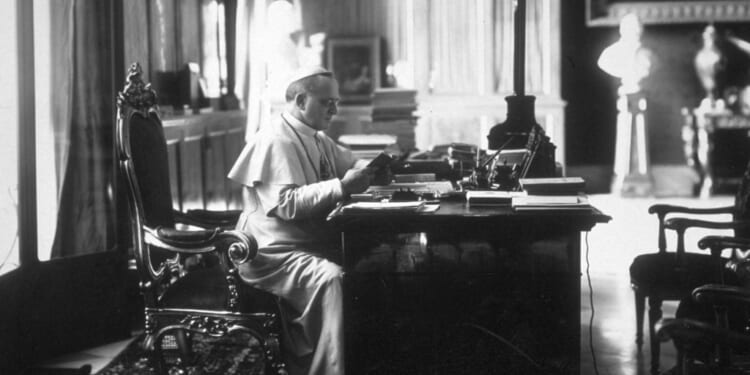

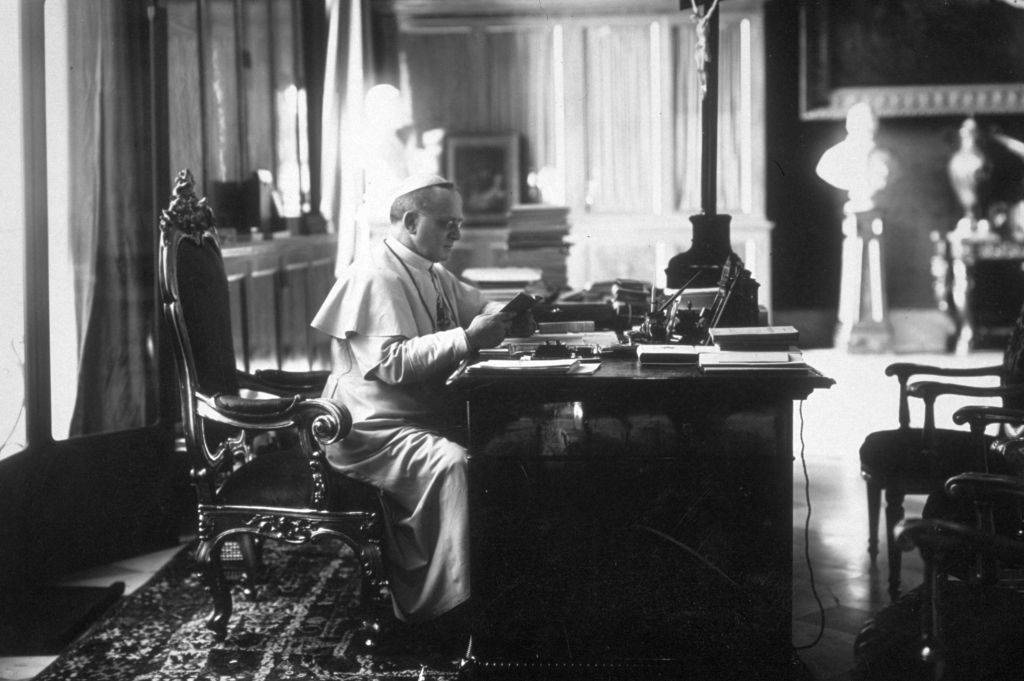

Among my fellow Catholics, the apologists of the pre-war church sometimes get this wrong and connect antisemitism with racism and point to how the church always condemned that. And yet one can find antisemitism in the writings of many prewar Catholic thinkers and clergy, some of them even saints. Usually, the editors of their texts leave those parts out, as is the case in some editions of the works of G.K. Chesterton. One defense of people like Chesterton and his friend Hilaire Belloc is that they did not hate Jews and that they rejected Nazism. Chesterton himself expresses this paradox, “in our early days, Hilaire Belloc and myself were accused of being anti-Semites. Today, although I still think there is a Jewish problem, and that what I understand by the expression the Jewish spirit is a spirit foreign in western countries, I am appalled by the Hitlerite atrocities in Germany.” Indeed, the church condemned racism–Pope Pius XI, a just and sensible man who was typically a moderating influence in politics, even explicitly condemned Nazi racial theories, as did most Catholics. But Nazi racial theories were hardly the extent of the problem.

Before the war, antisemitism was much more widespread than Nazism itself. It was everywhere in Europe, among both the laity and the clergy, on the left and right. Among reactionary thinkers in France, Jews were often blamed for political conspiracies in favor of liberal and republican government, and against monarchy, as well as other social upheavals. These reactionaries, like Louis Veuillot, were not just critical of the tragic terror of the second phase of the French Revolution, they were critical of the entire project of reform, romanticizing the old regime, and even calling for the reversal of the revolution’s emancipation of Jews (making Jews full citizens like everyone else).

The aim of reversing Jewish emancipation was typical of reactionary Catholics and even infected the clergy. In 1890, the Roman Jesuit journal La Civiltà Cattolica published an article calling for a significant reversal of Jewish emancipation. These reactionaries frequently seized the language of a “Jewish question” or “Jewish problem.” And this framing was not innocent. One of the main reasons Jews were seen as a “problem” by the reactionary tradition was because they understandably supported political movements that did not exclude them, and they therefore tended to favor republican/liberal politics—though, admittedly, in continental Europe (unlike the United States), liberal politics was often anticlerical as a result of polarization. In reality, Jews were no more a “problem” than Catholics in a Protestant country. America was proof that they could fit in and succeed without harm to anyone else.

In France, scapegoating of Jews got particularly ugly in what is called the Dreyfus Affair, when, beginning in 1894, French republicans came to the support of a Jewish man, Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery officer who had been falsely accused of treason. It was a mark of tribal legitimacy for reactionaries on the right to call him a traitor and demand that he be convicted. For this reason, belief in his guilt lasted among the reactionaries long after he had been vindicated.

This French reactionary antisemitism came to a head in 1940, when the Nazis invaded, France surrendered, and Philippe Pétain became the dictator. Right-wing reactionaries, (including the vast majority of French bishops) were all too happy for the regime to enact laws that limited the civil rights of Jews. Many of those same bishops would later regret this when the cruelty of the anti-Jewish legislation became too blatant to ignore. In the end, around 70,000 Jews who had been under the jurisdiction of Vichy France would perish in concentration camps.

Such antisemitism was not always in bad faith; sometimes it was just casual acceptance of common narratives. For instance, not everyone who believed the Protocols of the Elders of Zion–which purports to be the minutes of a meeting of powerful Jewish leaders and was exposed as a forgery in 1921–was evil or even culpable; they often took it as a fact, and were merely duped by the initial scapegoaters. But many were still culpable, either because they helped produce such conspiracy theories or because they credulously accepted them. God only knows how to sort the sheep and goats in this affair, but it was tragic and embarrassing—and it ultimately contributed to the deaths of millions of Jews by helping fuel the antisemitism of the Nazis.

And today, we see those mistakes repeated. People like Fuentes find pre-war antisemitism and embrace it. They fail to see the absurdity of the conspiracy theories that tried to justify it. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was, for instance, entirely debunked, proven to be a forgery by Russian secret police of a 19th-century satire. The Judeo-Masonic-Bolshevik conspiracy theory, which was the most popular Jewish conspiracy theory by the time of the 1930s (connecting Jews with Freemasons, liberalism, capitalism, and the Bolsheviks), was literally incredible: Why would Jews conspire to promote both capitalism and communism? Where is the evidence for this, other than the unsurprising presence of Jews in political groups that oppose a politics that would exclude them?

There is also the long history of blaming Jews for usury and other economic sins. It is well known that Jews were traditionally often forced to work in finance and other “middleman” occupations (those between producers and consumers) because they were excluded from other jobs. This gave them the historically persecuted status as “middleman minorities,” making them victims of the economic ignorance of the masses. In truth, any mainstream economist today will tell you that these middleman roles are critical for the economic prosperity that benefits us all. So, you see, antisemitism isn’t just evil, it’s ignorant.

That is why certain moves of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s were so important. In the Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate, for instance, the world’s bishops united with the pope in changing the conversation about the church’s relationship with Jews, positively affirming the “spiritual patrimony common to Christians and Jews,” and seeking “to foster and recommend … mutual understanding and respect.” It also clarified that Jews hold no collective responsibility for the death of Jesus Christ, countering an old antisemitic accusation that was based on bad theology. The Council also “decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism … directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.” Post-conciliar popes like John Paul II upheld this attitude, referring to the Jews as “elder brothers” in the faith.

The Council likewise addresses the problem of the kinds of political arrangements that foster antisemitism in its Declaration Dignitatis Humanae, which affirms some of the central assumptions of liberal democracy, namely, the civil protection of fundamental rights, particularly religious freedom. This builds on Pope John XXIII’s encyclical Pacem in Terris, which affirms liberal democracy’s emphasis on special civic protection of human rights. What was particularly novel in Dignitatis Humanae was the affirmation of a civil right to religious liberty—a move made possible by the work of people like Jacques Maritain and Charles Journet, two respected Thomists who had also supported the French Resistance against Vichy during World War II.

It is critical that my fellow Catholics and I learn from these historical embarrassments instead of hiding them behind historically ignorant apologetics. The Second Vatican Council was right to respond to antisemitism by abandoning the politics for which Jews became a “problem” in the first place, affirming liberal democracy and the civic protection of religious liberty. And the Council was right to promote an improved relationship between Catholics and Jews. If history is to be a source for theology, it should be accurate history and not the history we prefer happened. We cannot make those mistakes go away, but we can stop them from being repeated.