“This will not be a partisan CR,” Johnson said at a press conference Tuesday. “It will be a clean, short-term continuing resolution. End of story.”

Now begins the game of trying to get enough votes to pass it. House Republicans, as usual, must worry not just about Democrats but about the fiscal hardliners within their own party. They have a record of opposing CRs, and many have already said that they will reject this one.

“I already hated status quo thinking and approaches (soft incrementalism at best), so I’m out on another CR for the sake of more government,” Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio tweeted this week. Reps. Thomas Massie of Kentucky, Victoria Spartz of Indiana, and Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia have all suggested they are voting or leaning no. However, such members (excluding Massie) often indicate they will vote against legislation only to end up supporting it. House Republicans can lose only three votes and still pass the CR.

Should Johnson succeed in pushing it through his chamber, it will then be up to Democrats in the Senate to decide whether to filibuster the bill and shut down the government, or to pass it. Faced with this decision six months ago, enough Democrats joined Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer—who feared that a shutdown would make it much easier for Trump and Elon Musk to remake the federal workforce—to advance the bill toward final passage.

That might happen again, but—for now—Democrats are showing more backbone. At a Tuesday presser, Schumer insisted things are “much different now for at least three reasons.”

First, he argued that Republicans are more vulnerable due to the unpopularity of their One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Second, he said Democrats are unified in their messaging against this CR. Third, he cited the “lawlessness” of the Trump administration since March, naming rescissions and impoundments as examples.

But Democrats have not been totally clear about why they oppose this CR. Asked what specifically the party objects to, Sen. Brian Schatz of Hawaii, a Democrat on the Appropriations Committee, did not name any particular provision. Instead, he noted comments from Trump and Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought indicating they do not have an appetite to work with Democrats.

“[Vought] said the appropriations process should be less bipartisan. And then, Donald Trump, two days ago, goes on Fox and Friends and says, ‘I don’t want you to deal with those people,’” Schatz told TMD on Wednesday. “And so, I’m not sure why you’re talking to us. Those guys have to figure out whether they want our votes or not.”

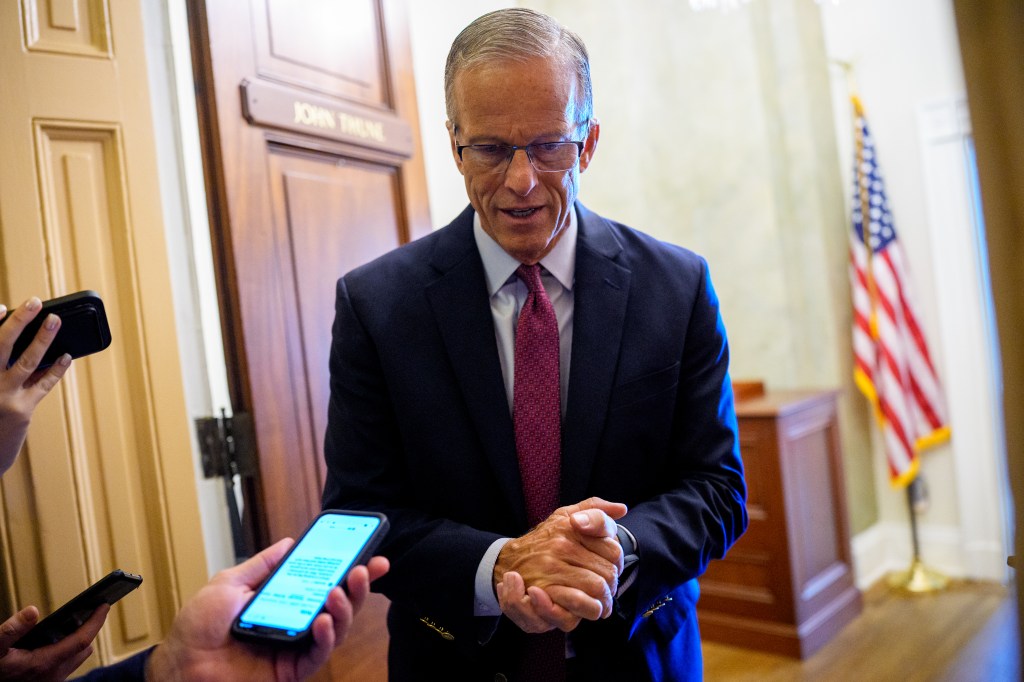

Democrats have said they want some negotiation over the CR, which Republicans produced on their own. “What’s to negotiate? It’s a clean CR,” Senate Majority Leader John Thune said at his Tuesday presser. But he added, “My office is right here. Chuck’s is right here. It’s very easy for him to come [from] here to here, or to say we need to have a conversation about this CR.”

However, Schumer has said Thune has not been so willing to talk to him. “Leader [Hakeem] Jeffries and I have been asking Thune and Johnson to negotiate from July,” he said. “He’s the leader of the Senate. What have we heard from them? Crickets, nothing.”

Democrats on Wednesday night unveiled their own CR, which extends government funding until October 31 and does not allow for the rescission of funding that has been appropriated in a bipartisan way. It also reverses health care provisions in the Republicans’ One Big Beautiful Bill Act and permanently extends enhanced tax credits for people who buy health insurance through the Affordable Care Act. The credits were passed by Congress in 2021 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they are set to expire at the end of the year.

Republicans have objected to tackling the tax credits in this spending battle. “That is a December policy issue, not a September funding issue,” Johnson said at his press conference this week.

That’s the state of play now. It’s questionable whether Johnson can get the CR through his chamber, and even if he does, Senate Democrats can filibuster it and shut down the government, causing agencies to pause nonessential functions and public employees to go temporarily without pay. The likelihood of a shutdown grows each passing day without a deal, but one shouldn’t overstate the possibility of it actually happening. The past two spending battles in December and March both had moments where it looked like the government was about to shut down, yet it did not in either case. It would not be surprising if Congress gets a last-minute plan done, like usual.

But how did we get to this point? Why is it that, especially in recent years, Congress has had to scramble right before the deadline to get a bill done and avert a shutdown?

“We’re not getting our jobs done in time, pretty simple,” House Appropriations Committee Chairman Tom Cole of Oklahoma told TMD. “If people just do the work, we can get it done.”

Appropriators in both chambers had more than six months to finish all 12 bills. Cole noted that his committee advanced all of them to the floor. But the House only passed three of them. The Senate, meanwhile, has also passed three bills, but a further four have not made it out of committee. This dysfunction is not new. Congress has only passed all of its appropriations bills on time four times: 1977, 1989, 1995, and 1997.

“It’s been years since we’ve been anywhere near regular order on appropriations,” Senate Minority Whip Dick Durbin of Illinois, who is set to retire in 2027 after finishing his fifth term, told TMD. “I can’t explain to you how we’ve reached this point, but it’s very disappointing.”

There are a few ideas floating around for how to get Congress out of the morass of rushing to avoid a shutdown. Noting that “the appropriations process is obviously too unwieldy,” Democratic Sen. Chris Murphy of Connecticut suggested reducing the number of bills Congress needs to pass and floated making Congress go through the budgeting process every two years rather than annually.

Republican Sen. James Lankford of Oklahoma first introduced his Prevent Government Shutdowns Act in 2019. Under his bill, if government funding lapses, it would automatically be extended at current levels on rolling 14-day periods until Congress passes the actual appropriations bills. The legislation would also deter lawmakers from leaving Washington until the bills are finished. “Our focus is, let’s find a way to be able to make this stop and to be able to keep us working until we actually get it done,” Lankford told TMD.

But others insist that the fix lies less in policy prescriptions than it does with individual members of Congress. “It just means behavior has to change,” said Republican Sen. Thom Tillis of North Carolina, who is retiring after the 2026 midterms. “And stop taking the bait from voices at either end of the spectrum that think that this is what Congress looks like at its best. It’s not.”

GOP Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana gave his own idea for how to return to regular order in the appropriations process: “People taking their meds and acting like adults,” he told TMD.