If Nathaniel Hawthorne were alive today, he—like President Donald Trump—would “HATE TAYLOR SWIFT.”

Or maybe not. Maybe today Trump likes Taylor Swift—who knows? Either way, liking or disliking Swift has become a cultural litmus test, a shorthand for what kind of aesthetic taste—or moral temperament—you claim to have. Some admire her sincerity; others sneer at her sentimentality. Either way, the debate says more about us than it does about her.

So I invite you, whether you consider yourself a Swiftie or not, to keep reading—to think about why this one artist inspires such intensity, and why that’s nothing new.

Travel back with me to 1855. Nathaniel Hawthorne, writing to his publisher, grumbled that he could not seem to achieve the success he wanted in the literary marketplace. “America is now wholly given over to a damned mob of scribbling women, and I should have no chance of success while the public taste is occupied with their trash—and should be ashamed of myself if I did succeed,” he wrote.

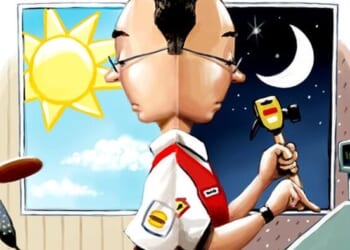

The “scribbling women” he had in mind were the 19th century’s bestselling authors—writers like Maria Susanna Cummins, whose The Lamplighter (1854) became a literary sensation. The novel, which tells the story of a poor girl who rises from hardship through courage and faith, sold 40,000 copies in its first month and 100,000 within a year—the 19th-century equivalent of a viral blockbuster.

Hawthorne hated it. “What is the mystery,” he wrote, “of these innumerable editions of The Lamplighter and other books neither better nor worse? Worse they could not be, and better they need not be, when they sell by the hundred thousand.” But there was no mystery at all. Cummins understood what women wanted from art: sincerity, moral imagination, and the courage to feel deeply. She wasn’t the indie darling of literary Boston—she was Taylor Swift, crashing the charts with a story about a girl the world had underestimated.

And women loved her for it. They loved, too, the sentimental March sisters of Little Women—a novel popular not because it was taught in schools but because it was often passed down, generation after generation, from mother to daughter. Authors like Louisa May Alcott, Cummins, and Harriet Beecher Stowe were all 19th-century celebrities in this mold—and whose work was often dismissed by elites. In 1877, literary critic Thomas Wentworth Higginson of Atlantic Monthly fame said of Alcott, “Her muse was sociable; the instinct of art she never had,” even though Little Women was a runaway bestseller that continues to form generations of readers.

Fast forward to 2025. Taylor Swift’s The Life of a Showgirl came out on October 3, and as of Sunday has reached its sixth week at No. 1 on the Billboard 200. Yet the reviews sound eerily familiar. The Standard declared, “She’s back mining her life for content, and all that glitters down there is certainly not gold.” America Magazine was even harsher: “Now, with a genuine failure on her hands, one can only hope that some sense is knocked into Swift.”

If Hawthorne’s sneer at “scribbling women” dismissed female authors for being too emotional, these critics do much the same. Replace the quills with guitars, and it’s the same story: women writing about feelings that connect with a largely female audience, often dismissed by critics, adored by fans—whose opinions, being mostly women’s, are seen as less discerning, less serious, less sensible. The assumption—then and now—is that women’s emotions distort their judgment. Now, this is not to say that all women love Taylor Swift. But considering that The Life of a Showgirl is the best-selling album in the modern era according to Billboard, it’s safe to say the album is resonating with the public. Moreover, as I pen this article, “The Fate of Ophelia”—a ballad that lifts Hamlet’s drowned maiden back into the light—is still floating easily atop the charts.

Taylor Swift, I suggest, is the most important sentimental artist of the 21st century—not sentimental as in cheap tears, but in the classical sense: She’s an artist who teaches a culture how to feel.

Harriet Beecher Stowe once said her mission was to help her audience “feel right.” The sentimentalists believed that feeling could be a way of knowing, that empathy, tenderness, and moral imagination were as important as intellect or logic in understanding truth. Their novels didn’t just entertain; they formed consciences and emotional palettes. They taught readers to perceive the suffering of others as a moral call to action. That was sentimental art at its height: fiction that moved hearts so powerfully it moved nations. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is the most famous case—so influential in forming public opinion on slavery that Abraham Lincoln (likely apocryphally) called her “the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” Other sentimental works accomplished similar moral labor: Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World helped spur women’s charitable reform movements, and Harriet Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl used sentimental strategies to awaken abolitionist conviction and early feminist consciousness.

I’d argue that the same sentimental ethos animates Swift’s work. Take the short film that accompanies her song “All Too Well.” It’s cinematic sentimentalism: We watch a red-haired young woman, over the course of 15 minutes, move through intense love, loss, and reckoning. There’s the giddy intimacy—laughing in the car together, dancing by refrigerator light. And then there’s the low point: Heartbroken, the girl is prostrate, alone in bed—a tableau straight out of a 19th-century illustration. In the film’s epilogue, she writes a novel based on the experience—and by writing the story herself, by taking her emotions seriously, she claims the fullness of her experience—good and bad—while offering something to others who might find solace through her art.

The internet is the internet, though, and the crying scenes in the short film have already been packaged into reaction images and gifs, clipping the slow emotional buildup of Swift’s artful, affective short film into parodied shorthand. Indeed, the red-haired actress’s blotchy, crying face has become a meme of its own for any overwrought feeling from a woman on the internet. We reduce relationships to their lowest points, the real to the meme. Women may get a moment—maybe—but the internet swiftly prunes it. It’s as if sincerity has an expiration date the moment it hits the algorithm.

Real emotion is hard to express in a culture that rewards short attention spans—and detachment. We’re allowed to be clever, detached, ironic. But not heartbroken. Not as devastated as the actress looks in that bed. Online culture keeps telling women to perform strength (“Girl, you’re enough”), but never vulnerability, as if feeling too much is a moral failure.

For the sentimental imagination—for Swifties—tears aren’t hysteria; they’re healing. They make inner truth visible. In an age of irony, Swift’s listeners enact the same emotional ritual the sentimental novel once invited: to weep, to remember, and to be remade by what we’ve felt.

Yet sentimentalism was never only emotional: It was domestic and material. It rose alongside commodity culture in the mid- to late 19th century, when industrialization made goods cheaper and more widely available and the growing American middle class—especially women—suddenly had both leisure time and discretionary income. By the 1850s, new printing and manufacturing technologies produced an explosion of sentimental objects: keepsake albums, mass-market gift books, lockets, mourning jewelry, embroidered samplers, and the first waves of children’s dolls tied to literary characters. Department stores and mail-order catalogs followed in the 1870s. Objects became moral technologies in the 19th century—tokens that made feeling visible, portable, and shared.

That’s the same emotional economy Swift has revived. Her friendship bracelets, cardigans, vinyls, and candles are modern sentimental artifacts. They turn interior emotion into something tangible. When Swifties trade bracelets or sing the lyrics to “You’re On Your Own, Kid” together in a stadium, they’re not only participating in fandom; they’re also practicing empathy. “Make the friendship bracelets, take the moment and taste it,” she sings, an invitation to take something immaterial and make it material, a pattern familiar to anyone formed by a tradition or community that binds its people through tangible signs. Further, it’s worth noting that the whole bracelet-trading practice was pushed further into the spotlight by one particularly famous bracelet: Travis Kelce’s handmade attempt to slip Swift his phone number. That famous “small token” has now been folded into a very public love story. Indeed, Swift once sang she’d “marry with paper rings,” and perhaps that line captures her appeal: In her world, the simplest objects become meaningful when a community decides they are—when a person decides they are worth passing along to someone else they care for.

Critics, of course, miss this. They see merchandise and smart marketing where many women see meaning. They roll their eyes at bracelets and candles, never realizing that these small, domestic gestures—the gifts, the keepsakes, the shared tokens—are what have always held women’s worlds together. My daughter and I make bracelets together and sing Taylor Swift songs, because domestic arts are bound up with sentimental art: They both make love material, feel-able. Critics might see and scoff at consumption where others see, and build, communion.

Ultimately, Swift, like Cummins, knows what a lot of women want from art: sincerity, connection, moral imagination. Her songs alchemize private heartbreak into public grace. They reject irony as a worldview and instead invite vulnerability as truth.

I first listened to Taylor Swift with my mother, who’s since passed away; now my daughter sings her songs with me. Three generations of women, linked by melodies. It’s the same chain that once passed Little Women from mother to daughter, teaching not just how to read but how to feel. This Christmas, I plan to read Little Women with my daughter, as my mother once read it with me. As literary scholar Beverly Lyon Clark notes in “The Afterlife of ‘Little Women’,” the novel inspired everything from “Jo March clubs” to multigenerational reading circles—evidence that women treated the book as an emotional inheritance.

If Hawthorne thought that “mob of scribbling women” threatened to overturn the hierarchy of taste, he was right. They did. Hawthorne wrote about sin; Swift writes about sincerity. It’s funny, then, that in the “New Romantics” she sings, “We show off our different scarlet letters—trust me, mine is better.” In that line, she speaks back across centuries—to Hawthorne, whose moral suspicion of sentimental women writers helped define the critical disdain they faced, to every critic who mocked women for feeling too much. Where Hawthorne wrote of Puritan guilt, Swift writes of productive grace. That’s the new romanticism—the new sentimentalism—once again taking the “damned mob” by storm: not irony, but feeling reclaimed.