At the beginning of May, when President Donald Trump announced his first appeals court nominee of his second term in office, judicial conservatives were pleased—and relieved.

Whitney Hermandorfer, Trump’s nominee to serve on the 6th Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals, was not the kind of crony some feared he might nominate in a second term after explicitly campaigning on a theme of retribution. She was exactly the kind of high-caliber judicial pick Trump made during his first term: Now serving as a lawyer in the Tennessee attorney general’s office, Hermandorfer had clerked for Supreme Court justices Samuel Alito and Amy Coney Barrett, as well as Justice Brett Kavanaugh when he was an appeals court judge.

That sense of relief would not last through the end of the month.

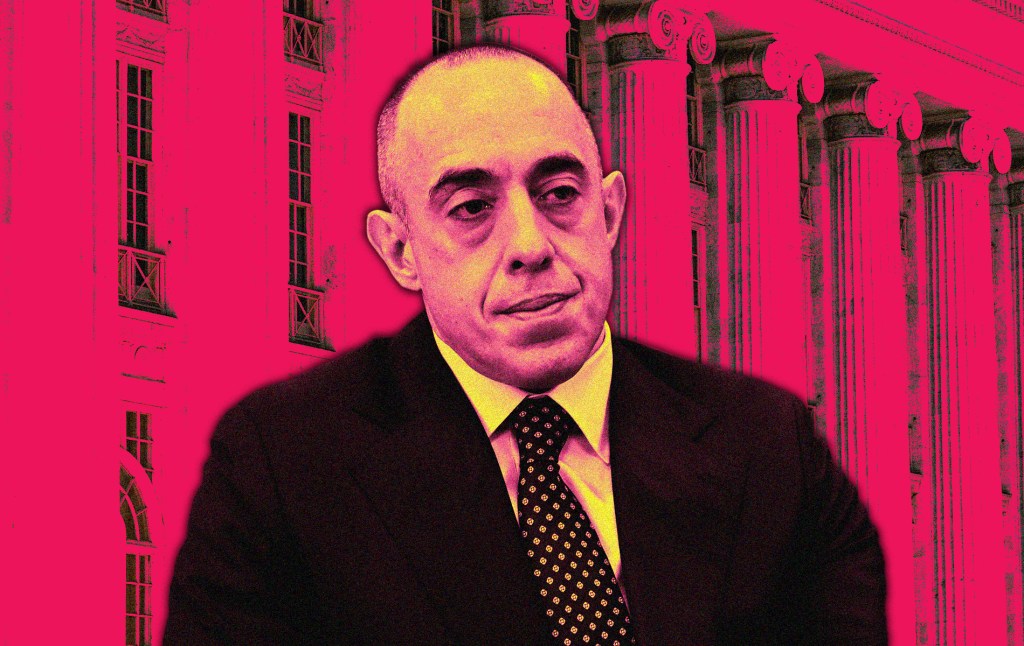

On May 28, Trump nominated to the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals his former personal defense attorney, Emil Bove. From January to March, Bove courted controversy in his role as acting deputy attorney general at the Department of Justice, where several prominent conservative legal thinkers contend that Bove demonstrated a willingness to put his personal loyalty to Trump above fidelity to the rule of law. Some judicial conservatives are now calling for Bove’s nomination to be defeated, but The Dispatch’s conversations with GOP senators this week suggest it’s too early to say if there will be a successful revolt against Bove.

“Emil is SMART, TOUGH, and respected by everyone,” Trump wrote in his Truth Social announcement of the Bove nomination. “He will end the Weaponization of Justice, restore the Rule of Law, and do anything else that is necessary to, MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN. Emil Bove will never let you down!”

Inside the Department of Justice, Bove proved he would never let Trump down in more ways than one. For example, Bove purged prosecutors involved in cases against January 6 rioters—despite the fact that Bove himself led efforts to prosecute January 6 rioters in New York.

But the greatest controversy from Bove’s brief tenure as acting deputy attorney general was his role ordering prosecutors in the Southern District of New York, where Bove himself was once a prosecutor, to dismiss charges against New York City Mayor Eric Adams, a Democrat. In a damning 57-page indictment, prosecutors made the case that Adams had taken bribes and solicited illegal campaign contributions in the last decade. Not only had Adams accepted more than $100,000 in luxury travel from Turkish sources, he also had sought illegal foreign campaign contributions through straw donors, according to the indictment, then repaid his foreign benefactors with official acts.

On February 10, Bove sent a memo to federal prosecutors in New York ordering them to drop the case against Adams on the grounds that the prosecution was politically tainted. “It cannot be ignored that Mayor Adams criticized the prior [Biden] Administration’s immigration policies before the charges were filed,” Bove wrote. He argued that the Adams prosecution “improperly interfered” with Adams’ ability to campaign for reelection in 2025 and argued that the prosecution also restricted the mayor’s ability to combat illegal immigration. Bove analogized the Trump Justice Department’s dropping the charges against Adams in exchange for tougher immigration enforcement to the Biden administration releasing Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout in exchange for an American athlete who was effectively being held hostage in Russia.

In the same memo, Bove conceded the Justice Department had reached its conclusion to drop charges “without assessing the strength of the evidence or legal theories on which the case is based.” On February 12, Danielle Sassoon—the Trump-appointed interim U.S. attorney who had assessed the strength of the Adams case—replied to Bove’s request in an eight-page letter to Attorney General Pam Bondi, saying she could not find any good-faith reason to carry out Bove’s order to dismiss the charges. Such an unwarranted dismissal was a corrupt quid pro quo—dropping charges in exchange for immigration enforcement—not the impartial administration of the law.

Bove’s explicit comparison of the dismissal to a prisoner exchange with Russia was “particularly alarming,” Sassoon wrote, adding that she had attended a meeting with Bove and Adams’ counsel on January 31 in which Adams’ counsel indicated the mayor would assist the Trump administration’s policy priorities “only if the indictment were dismissed. Mr. Bove admonished a member of my team who took notes during that meeting and directed the collection of those notes at the meeting’s conclusion.”

Sassoon picked apart Bove’s memo point-by-point. While Bove alleged the Biden-appointed U.S. attorney Damian Williams tainted the case, Sassoon pointed out that the investigation began before Williams “took office, he did not manage the day-to-day investigation, and the charges in this case were recommended or approved by four experienced career prosecutors.” She noted that prosecutors had followed DOJ guidelines on the timing of bringing charges against potential candidates for political office.

Bove responded not only by accepting Sassoon’s resignation—he wrote that she would be investigated by the Department of Justice’s Office of Professional Responsibility and accused her of failing to uphold her oath by suggesting she retained “discretion to interpret the Constitution in manner inconsistent with the policies of a democratically elected President and a Senate-confirmed Attorney General.”

Bove’s treatment of Adams and Sassoon triggered a widespread backlash from judicial conservatives—and led to several more resignations at both the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan and at the Department of Justice (where Bove had transferred the case). Hagan Scotten, the assistant U.S. attorney who led the Adams prosecution, wrote in his resignation letter: “No system of ordered liberty can allow the Government to use the carrot of dismissing charges, or the stick of threatening to bring them again, to induce an elected official to support its policy objectives.”

Scotten, like Sassoon, had once served as a Supreme Court clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia. He added in his letter to Bove that he did not have a generally negative view of the Trump administration and could even understand why a president “whose background is in business and politics” might see dropping the Adams charges as a “good, if distasteful, deal.” But Scotten concluded:

Any assistant U.S. attorney would know that our laws and traditions do not allow using the prosecutorial power to influence other citizens, much less elected officials, in this way. If no lawyer within earshot of the President is willing to give him that advice, then I expect you will eventually find someone who is enough of a fool, or enough of a coward, to file your motion. But it was never going to be me.

Plenty of conservative legal thinkers were appalled by Bove’s behavior. Andrew McCarthy—a former federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York who was touted by Trump just last year as “highly respected”—told The Dispatch: “I sure hope I would have done exactly what [Danielle Sassoon] did. I was very proud of her.” McCarthy, who now writes for National Review, said that the Adams case will be a central issue at a Bove confirmation hearing in the Senate (which has not yet been scheduled). “When you’re talking about a circuit court judge, fidelity to the law is the thing that’s important, and [Bove is] obviously being put in there above a number of people who are more, on paper, qualified for the position than he is, because he’s Trump’s guy,” McCarthy said. “If the Adams case stands for anything, it stands for the likelihood that when push comes to shove, [Bove is] not going to do the legally right thing. He’s going to do what the president wants, which isn’t always the same thing.”

McCarthy added that if he were a senator he “wouldn’t be inclined to support him, but I’m not dogmatically opposed to him.” He said he would want to hear Bove’s testimony and “know what’s coming behind him” because Trump “could have a worse nominee.”

But Gregg Nunziata, former Republican Senate Judiciary Committee counsel, told The Dispatch it is imperative that Senate Republicans defeat the Bove nomination. “I think Senate Republicans will understand as all conservatives should understand, this isn’t about just one seat on the 3rd Circuit. This is about the signal we’re sending the White House on what conservatives will accept in judicial nominations generally, including in the case of a potential Supreme Court vacancy,” said Nunziata, the executive director of the Society for the Rule of Law. “Not only was the administration’s behavior in the Adams case fundamentally corrupt and unlawful, [Bove’s] handling of it was clumsy to say the least.”

Nunziata pointed to the conservative movement’s stance against Harriet Miers, President George W. Bush’s Supreme Court nominee who withdrew due to concerns about her judicial philosophy and qualifications, as an example for conservatives to follow today. “It divided the right at the time, but 20 years ago, it was extremely important that many prominent figures in the conservative legal movement and conservative Republican senators said no to Harriet Miers,” he said. “The president does not get to pick whoever he wants for a vacancy, and expect us to rubber stamp … someone whose primary qualification is devotion to the president and his agenda.”

But in the Capitol this week, there was no sign yet of a public GOP backlash against Bove that would sink his nomination. “I haven’t looked at it yet, but I’ll go into it objectively [and] independently,” North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis, up for reelection next year in a battleground state, told The Dispatch. Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, who has defied the president over tariffs and spending, said of the Bove nomination: “I don’t know anything about it.” Missouri Sen. Josh Hawley, asked if he had any concerns over Bove’s handling of the Adams case, told The Dispatch: “Not really.” But Hawley, a Trump loyalist, didn’t jump to Bove’s defense and said he didn’t have a sense of his judicial philosophy: “I’ll want to explore that.”

The fights over Trump’s most controversial Cabinet nominees revealed three Republican senators—Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, Susan Collins of Maine, and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska—were willing to vote “no” on at least some Trump nominees. But a fourth, necessary to defeat a Trump nominee in a Senate controlled 53-47 by the GOP, proved elusive. The Wall Street Journal reported that Tillis was going to join McConnell, Murkowski, and Collins to sink the defense secretary nomination of Pete Hegseth but reversed course under pressure from the Trump administration hours before the vote. The lone example of the Senate standing up to Trump in his second term was over the nomination of former Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz to serve as attorney general; Gaetz withdrew when it was clear there weren’t enough votes.

There is, of course, a major difference between confirming executive branch appointees tasked with carrying out lawful orders from the president for up to four years and nominees who are supposed to be independent judges serving for life.

Whether the Adams case is enough to sink Bove remains to be seen. Two Democrats on the Senate Judiciary committee, Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut and Chris Coons of Delaware, told The Dispatch they’d like to hear testimony from Sassoon and Scotten at a Bove confirmation hearing. “I’d like to hear them testify … Their reasons for resigning are pretty searing indictments of the decisions he made at the Department of Justice,” Blumenthal said. But, he added, Republicans who control the judiciary committee “can decline to hear anyone they want to reject.”