British law doesn’t mandate another general election until August 2029, but internal party fractures could force Starmer out well before that. And with both Labour and the Conservatives languishing below 20 percent in the polls, Britain’s century-old two-party system may be on the way out, too.

An inability to set a clear course lies at the root of Starmer’s unpopularity. He arrived at Downing Street promising to align the government around five missions, ranging from promoting economic growth to reforming the National Health Service. But the government has continually waffled.

“They just don’t have a clear sense of what they want to achieve in government,” Sam Freedman, a former government adviser for the Department for Education under David Cameron and political analyst who writes the Substack, Comment is Freed, told TMD.

Labour campaigned on a promise not to raise taxes, but for months, Starmer and Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves have regularly implied they may have to do so to plug the budget deficit. Then, on Friday, publications reported that Reeves was no longer planning to raise income taxes, sending the bond markets into chaos on the conflicting news.

In a May speech, Starmer promised to reduce legal immigration levels and crack down on illegal migration, warning that Britain risked becoming an “island of strangers” without “fair rules.” The Labour Party’s left immediately erupted in outrage, with some Members of Parliament (MPs) comparing Starmer’s remarks to the infamous 1968 “rivers of blood” speech from anti-immigration politician Enoch Powell. Starmer backed away from that language a month later, but persisted with plans to reduce immigration, pleasing no one.

“In many cases, MPs are really worrying that [Starmer] doesn’t even know what the government’s agenda is,” Philip Cowley, a professor of politics at Queen Mary University, London, told TMD. “There’s nothing there to sell.”

With Labour’s support collapsing, the most likely candidate to seize leadership of the opposition ought to be the Conservative Party (also known as the Tories), the world’s oldest political party. But they’ve struggled to recover from voters’ exhaustion with them after 14 years in power, and their new leader, Kemi Badenoch, has failed to attract much support.

“I think the Tories are pretty much stuffed,” Freedman argued. Hovering at 17 percent in the polls, with staffers and members fleeing to the party’s populist-right competitor, Reform, the Tories risk being locked out of power by Britain’s winner-take-all election system.

“The problem for the two main parties,” Cowley said, “is that once you’re not necessarily one of the two main parties, this thing comes around and kicks you right up the arse.”

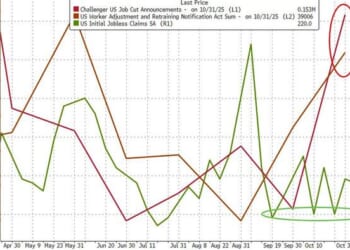

Currently, both Labour and the Tories are languishing below 20 percent in Politico Europe’s Poll of Polls. Three other parties, all of which currently hold seats in Parliament, are polling at 13 percent or above: the far-left Greens, the center-left Liberal Democrats, and the right-populist Reform Party, with comparatively mammoth support of 29 percent.

Reform—which began as the anti-E.U. Brexit Party—now threatens to supplant the Tories as Britain’s party of the right. Its founder, Nigel Farage, has elbowed aside Starmer and Badenoch as the dominant figure in British politics, with blistering critiques of the establishment and promises to drastically reduce immigration—alongside advertisements for gold bullion and paid Cameo videos.

Reform’s stances on migration are the most radically restrictionist in modern British political history. In September, the party rolled out an immigration platform that proposed abolishing the policy of Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR), which gives migrants the right to apply for benefits after residing in Britain for five years. Instead, Farage said that migrants should have to reapply for visas every five years.

Reform’s policy chief, Zia Yusuf, said the goal is for “hundreds of thousands of people having to apply and ultimately losing their settled status in the U.K.,” leading to their voluntary departure. Ben Ansell, a professor of democratic institutions at Oxford University’s Nuffield College, told TMD that “it would be the most extreme example that I could think of, of an anti-immigration policy in any wealthy country,” comparing it to the U.S. abolishing green cards. Farage has also promised large-scale deportations, although the details remain fuzzy.

Farage maintains that mass deportations, voluntary or not, will save Britain more than $300 billion over several decades, claims which Reeves claimed “have no basis in reality.” But after multiple Tory prime ministers, including Brexit leader Boris Johnson, presided over several years of record immigration levels—what Farage terms the “Boris wave”—a critical mass of British voters are indicating that they’re willing to turn to a new party.

Labour is also facing attacks from its own end of the ideological spectrum. The far-left Green Party, led by Zach Polanski, has seen a boom in membership and a rise in poll numbers, with Polanski accusing Starmer of threatening to “hand this country on a plate” to Farage by moving to the right on immigration. With a core of young, disaffected progressives, the Greens may be able to take several Labour seats in London, where such voters are concentrated.

Even smaller parties, whose votes are more concentrated than the Greens, will also take away seats. The Liberal Democrats have found success in southeast England and now hold 72 seats in Parliament. Plaid Cymru, the Welsh nationalist party, and the Scottish Nationalists are both strong in their respective nations. In a special election for a seat in Caerphilly, Wales—which Labour has held for decades—a Plaid Cymru candidate won with 47 percent of the vote, ahead of Reform’s 36 percent. Labour finished with only 11 percent of the vote.

A five-party contest (with smaller parties in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland for good measure) is a novel development in British politics.

“It’s the first time this has happened, with so many parties,” Sir Vernon Bogdanor, a political scientist and historian of British politics at King’s College London, told TMD. Bogdanor also noted that in Britain’s winner-take-all system, a fractured electorate can lead to minority rule: Starmer won his massive parliamentary majority with only 34 percent of the vote, and Reform could feasibly win an outright majority with its current mark of 29 percent.

But why do voters’ frustrations seem to extend not only to the current government, but to Britain’s established party system? Its stagnant economy is a significant factor. Britain used to control an empire. Now, its economy has fallen behind Italy’s. Poland is expected to surpass Britain’s GDP per capita by 2040, potentially sooner.

The average Brit spends a third of his or her income on rent. The average house price is nine times higher than a year’s average wages. Inflation remains higher than government targets, and austerity measures are politically toxic in a country where average weekly wages have barely increased since the 2008 financial crisis. Roughly 10 percent of the population currently sits on a National Health Service waiting list, and prisons are so overcrowded that violent criminals are often released early. In this environment, Reform’s anti-immigration message is potent.

But it may be years until the next electoral challenge to Labour’s majority, Freedman noted, and the party still has time to turn things around. But even if it does, he said, “I suspect it will involve changing the prime minister, unless he can reveal a political ability that has so far not been apparent at all.”