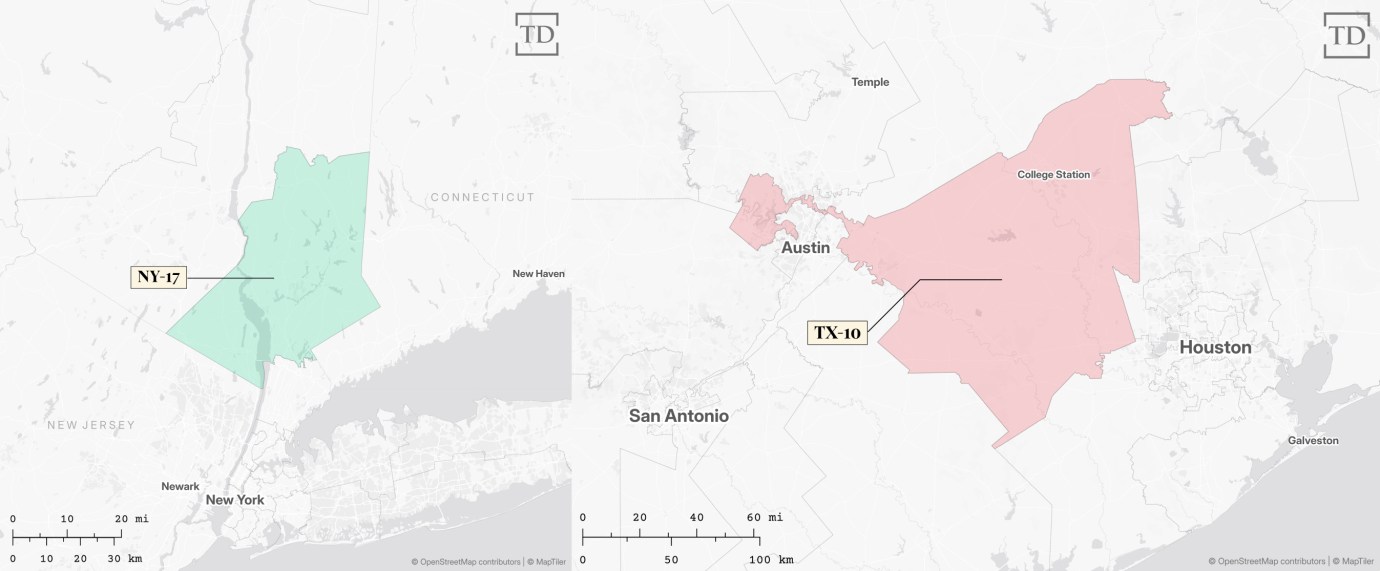

White House officials reportedly started floating the idea that Texas should redraw its congressional maps to gain more seats for the GOP back in June. By July, the suggestions had evolved into a full-court press, with President Donald Trump essentially ordering Gov. Greg Abbott and Texas Republicans to aim for a map that gained five House seats.

In private, many lawmakers reportedly opposed the idea. But in public, the state GOP quickly acquiesced. Abbott called for a special session to consider proposals for new maps, along with other legislative priorities, calling redistricting “an essential step for preserving GOP control in Congress and advancing the [sic] President Trump’s America First agenda” in a July 9 statement.

Democrats’ backlash was swift. Democrats in Texas’ House of Representatives quickly announced plans to leave the state, denying the House a quorum. With political and financial backing from party leaders, more than 50 Democratic leaders fled the state on August 3. Each lawmaker has incurred $500-per-day fines for being absent, but Democratic groups fundraised to help pay off the fees. Nationally prominent Democrats have also vocally supported the effort. “It’s not wrong what we’re doing. It’s self-defense for our democracy,” Rep. Nancy Pelosi, the former U.S. House speaker, said.

But even if Democrats successfully run out the clock on the special session that’s set to end Friday, they’ve conceded that leaving the state is likely just a stalling tactic to draw national attention to the dispute. “We said we would defeat Abbott’s first corrupt special session, and that’s exactly what we’re doing,” Gene Wu, the minority leader of the Texas House of Representatives, said Tuesday. But Abbott has vowed to call “special session after special session until we get this Texas first agenda passed.” He also filed an emergency petition to the Texas Supreme Court to have Wu removed from his position for abandoning his office, and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton called for prominent Democratic activist and former U.S. representative Beto O’Rourke to be held in contempt of court for allegedly illegally assisting Democrats in their effort to block the new maps. “It’s time to lock him up,” Paxton said in a statement.

There are, however, other arrows in the Democrats’ quiver, outside of Texas. The leaders of the two largest Democratic-controlled states—Gov. Gavin Newsom of California and Gov. Kathy Hochul of New York—have promised to redraw congressional districts in their own states in retaliation. “This is war. We are at war,” Hochul said earlier this month. She has said that if Texas goes ahead with redistricting, New York will attempt to change its laws to allow legislators to redraw its maps, which have been set by an independent commission since 2014. “I’m tired of fighting this fight with my hand tied behind my back,” she said. “With all due respect to the good-government groups, politics is a political process.”

Newsom, who hosted the self-exiled Texas Democrats in his state last week, has moved even closer to redrawing his state’s maps. He claims to be working with lawmakers on maps—to be released Friday—that would give California five more Democratic seats in its congressional delegation. But after voter initiatives in 2008 and 2010, California has drawn its congressional districts through an independent commission. Newsom intends to get around the law by asking voters to approve new districts in a November special election.

But convincing California voters to sign onto his effort may be difficult. “The voters made this choice, twice, to take redistricting out of the legislature’s hands and create a bipartisan, totally independent redistricting committee,” Ken Miller, a political scientist at Claremont McKenna College and head of the Rose Institute of State and Local Government, told TMD. “If at the drop of a hat, the majority party tries to overturn that, it basically decimates the whole process of independent redistricting.”

There’s nothing new about lawmakers using the redistricting process to gain more seats for their party. The word “gerrymander” is a portmanteau of the name of Massachusetts’ governor in 1812, Elbridge Gerry, who signed a redistricting bill into law, and salamander, for the odd shapes some districts took.

The practice continued into the 21st century. After the Republican wave election of 2010, the party used its control of 25 state legislatures (the most for the GOP since 1928) to redraw congressional maps in ways that favored Republicans. “If you look historically at previous redistricting cycles, I think it is accurate to say that probably Republicans were generally gaining more seats than Democrats through gerrymandering,” Benjamin Schneer, an associate professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, told TMD.

But, Schneer noted, the shifts in where voters for each party lived in the past decade, along with the fact that both parties engaged in the process, moved the congressional balance back toward the center, leaving Republicans with only a slight advantage nationally. A 2023 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that by that year, the parties’ efforts at partisan gerrymandering had mostly canceled each other out, giving Republicans an edge of only two seats due to gerrymandering. “I do think nationwide things were as close to fair as they had been for a while, before this Texas thing,” Schneer said.

And none of this is to say Democrats haven’t gerrymandered as well. Republicans often point to Illinois, where seven out of eight congressional seats regularly go to Democrats, as an example of blue-state gerrymandering. But the party’s attempt to ban partisan redistricting at the federal level in 2021 along with political geography has made the current battle a somewhat unequal fight.

“The bottom line is, if Democrats had the ability to create a map where they could win all the seats in Illinois, they probably would do so, but they can’t,” Jonathan Cervas, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University who redrew New York’s district maps in 2022, told TMD. “The practical ability to gerrymander is different for the parties, because the underlying political geographies are different.” For example, 36 percent of Massachusetts residents voted for Trump in 2024, but none of its nine congressional seats went to the GOP—Republican voters are simply spread too thinly across the state.

However, if Texas moves ahead with its new map, sparking responses from New York and California, both parties might test just how far they can go. In response to Newsom’s threat, Abbott said that Texas might attempt to add 10 GOP seats to its delegation. In Indiana, Vice President J.D. Vance met with Republican leaders last Thursday to discuss redistricting, and on the same day, the Florida House of Representatives convened a select committee to examine the issue.

The moves might undo decades of gradual progress in red and blue states to take the power of redistricting away from partisan legislatures. “Gerrymandering is one of the few areas of modern democracy where things have been getting better over the last 10 or 20 years, because of citizen commissions, because of courts, in a few places because of bipartisan governance,” Sam Wang, a professor who heads Princeton University’s Gerrymandering Project, told TMD. “For it to fall victim to the breakdown in government at the national level would be to throw away one of the few bright spots in democracy reform.”