Authored by Dominic Adler via Substack,

The Telegraph published this headline yesterday: ‘Exposed: Labour’s plot to silence migrant hotel critics.’

The report concerns a team from the ‘National Security and Online Information Team (NSOIT)’, based in the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology. During last summer’s riots, NSOIT was tasked with monitoring ‘concerning narratives’ on social media and flagging them to technology companies such as TikTok for potential removal.

Here’s an email they sent.

The irony’s delicious – TikTok, long criticized for links to the Chinese Government, being asked to scrutinize ‘concerning narratives’ by the freedom-of-speech loving British Government?

This story broke in a week when the Government introduced the Online Safety Bill. The Technology Secretary Peter Kyle alleged Nigel Farage’s opposition to the legislation put him on ‘the same side as Jimmy Saville’ (an argument so specious I can’t be arsed to comment further). Kyle, it will be remembered, voted against an official inquiry into the Rape Gang scandal. It was also announced an ‘elite’ police team would be assembled to ‘monitor anti-migrant social media posts for early signs of unrest.’

In short? The Government seems overly concerned with information management, not border control. Perhaps it’s the logical end point of Blairite media doctrine. A genuine national emergency becomes an issue of perception and optics, not passports and deportations. You imagined that asylum hotel, peasants of Epping! That Afghan superinjunction? What superinjunction?

Yes, it’s a bloody liberty. But does it, fundamentally, constitute censorship? What’s really going on? Right now, issues around the internet, freedom of speech, public order, extremism and Government overreach are especially salient. For example, here’s a piece I wrote for UnHerd on the subject earlier this week.

My bona fides. I was a police officer for 25 years. I spent eight as a counter-extremism investigator at New Scotland Yard, both in Special Branch and SO15 (the Counter Terrorism Command). Just over a decade ago, I worked for two national units dedicated to online intelligence-gathering. One was an open-source counter-extremism team. The other was the Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU). I am a qualified advanced open-source and Covert Internet Investigator (CII). I have a certificate and everything.

I am, therefore, in a reasonable position to comment. A key theme of my writing is Policing’s post-9/11 surrender of counter-extremism policy to a securocracy comprised of academics, civil servants, activists and quangos. This, sadly, is the end result. The overt politicisation of the discipline into a purely political tool.

The first question I shall answer is simple – do the Government and Police censor social media?

Not exactly.

Would they like to?

Oh yes.

How, then, does it work? Why is the Telegraph’s story important? It demonstrates the influence government gently exercises over private companies, especially overseas – and over whom they have no jurisdiction. Governments exercise far more ‘soft power’ in this respect than police forces. After all, the NSOIT – based at the Department of Science – can influence policy impacting on Facebook, TikTok and X’s UK operations. Nice online platform you’ve got there… shame if something happened to it.

The process is fairly simple. I did this daily on the CTIRU, which was set up to try and remove violent extremism content from the internet. At the start of my shift, I would log on and begin searching for material concerning Islamist terrorism. This was during the early days of the Syrian war, and the appearance of Al-Shabaab in Somalia.

My preferred hunting ground was YouTube (we were expected to show a return of ‘takedowns’, to keep the stats monster happy), which back then was something of a Wild West. I’d find accounts hosting hundreds of beheading videos, DIY terror manuals, speeches inciting violent jihad and other nastiness. How, you might wonder, do counter-terrorism detectives go about removing this stuff from public view?

We send YouTube nice email asking them to remove it, because the content violates their terms of service.

That’s it. British police forces, quite rightly, have absolutely no power to sanction overseas social media platforms. Senior police officers, many of whom view the Internet as nothing more than a fiddly adjuct to their Sky package, struggle with this concept (more of which later).

You can see this voluntary, ‘ask nicely’ approach remains the case from the extract above. The civil servant manifestly isn’t ‘censoring’ anything. They’re asking the company, at a corporate level, to be mindful of such content and – if they wouldn’t mind – to remove it when it breaches their T&C’s.

Now, does this constitute censorship? The Government would argue it doesn’t. As they, rather haughtily, told The Telegraph:

[W]e make no apologies for flagging to platforms content which is contrary to their own terms of service and which can result in violent disorder on our streets, as we saw in the wake of the horrific Southport attack.

This is a tricky one. It assumes a rather Marxian interpretation of mass media’s impact on the hoi-polloi, whereby people uncritically accept information as if hypodermically injected into their minds. I’d also say Old Bill scouring the Internet for beheading videos is rather different from a civil servant flagging legal, albeit occasionally offensive, comments.

Which leads me to three things;

(1) The ghost in the machine – the attitudinal approach Governments display take concerning the Internet. Decisions are too often made by older officials and policy-makers who know absolutely nothing about technology.

(2) What I suspect is a generational difference around the potentially assaultive nature of language. Which is to say I (Generation X) was brought up as a ‘sticks and stones’ kind of person and not (like too many Millennials / Gen Z) a whiny snowflake. Not that it’s their fault – it’s the world into which they were hatched.

(3) The process I described earlier, whereby domestic extremism became a civil service discipline and, thus, a political plaything. We have seen this firsthand during COVID, and the explosion of nudge units, borderline psyops and state-sanctioned ‘fact-checkers’.

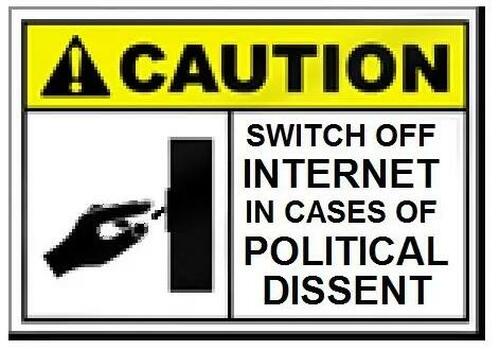

‘Switch off the Internet!’

Occasionally, when I wasn’t watching beheading videos, something online would annoy a senior officer. In this instance a well-known right-wing figure posted a ‘Threat to Life Warning’ he’d received from his local police, on what was then Twitter. It was scribbed on a piece of paper and put through his front door, along the lines of ‘here’s another TTL, mate, better do one ASAP.’ He juxtaposed it with what he said was the comprehensive police response plan for threats to a nearby Islamic cleric, thereby demonstrating allegations of two-tier policing are nothing new.

A senior officer appeared. ‘That force’s Chief Constable wants that tweet taken down!’ he said.

‘Why?’ I asked.

‘It’s embarrassing and reputationally damaging,’ the senior officer replied.

‘That’s hardly a criminal offence, boss,’ I explained, as patiently as I could. ‘And even if it was, Twitter’s an American company. Their EU office is headquartered in Dublin. And I’m not even going to ask, as it’s within their T&Cs.’

The senior officer was flummoxed. It hadn’t occurred to him we couldn’t simply ‘switch off the Internet’ at whim. This is the level of ignorance – and censoriousness – I routinely experienced.

This is the mindset of officialdom. It’s real. It’s frustrating. And, of course, peons like me (who knew the law) were treated as obstructive. As blockers, even.

I’m so glad I’m out of the fucking police.

This is their dream. It always has been.

Working in online monitoring, you’d occasionally attend meetings where senior officers discussed wishlists and ‘directions of travel.’ Back then, the Cameron government was obsessed with ‘network-level blocking’ technologies. So this is nothing new. The Online Safety Act has festered in civil servant’s imaginations since the Internet went live.

The assaultive nature of language

This is my second point, which concerns how younger people now view words as weapons. I touched upon this in my article about the Casey Report into the Met’s culture;

It’s simply a fact the Millennial and Generation ‘Z’ cohorts are more likely to view language as potentially assaultive in and of itself in a way my generation (Gen ‘X’) do not. I was brought up with a ‘sticks and stones’ attitude to language, teasing and what is now labelled ‘banter’. Put simply, a conversation I might see as someone else simply being a bit of a dick (dealt with by discussion) might now be perceived as being actively harmful (dealt with formally).

As a teenager I remember finding older peoples’ views on, say, race or sexuality cringeworthy too, although we tended to agree to disagree; not view them as harbingers of the apocalypse and Quite Literally Fascists.

Which is to say the new cohort of civil servants, MPs and police officers are naturally more censorious. I saw, during my service, too many drink deep of social justice Kool Aid.

For this generation, the real world and online worlds appear indivisible. We no longer teach proper critical thinking. We teach doctrinal obedience to a failing worldview – which is why the Government’s panicking so badly over the immigration crisis.

The Politicisation of Online Monitoring

My third point concerns how the police surrendered domestic extremism intelligence to the civil service. It might seem strange, in these days of Non-Crime Hate Incidents and hopelessly politicised police forces, but at least the police are obliged to pay lip service to proportionality. Yes, the civil service, being a government entity, is bound by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act too (RIPA), which regulates State snooping. Yet policing purposes and those of the civil service are subtly different. The civil service is inherently political. It exists to implement the will of ministers. Not enforce the law.

Incidentually, here’s a tip for interested parties. Send a FOIA request to the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology, asking for details of precisely the kind of RIPA training NSOIT officials receive when snooping on members of the public. Then ask, given they’ve agreed to ‘share police reports/factual cues wherever we can’ with foreign, third party social media companies, what MOPI (Management of Police Information) safeguards are in place? You’ve done all that stuff, guys. Haven’t you?

Since COVID and the ‘great awokening’, along with the plague of misinformation / disinformation monitoring, our once larval Ministry of Truth seems to have become a growth industry. What used to be small teams of investigators looking to identify troublemakers has mutated into a monster – a panopoticon of data aggregation, used to influence corporate bodies into bending to the Government’s will.

And now, instigated by the last Conservative administration but enthusiastically endorsed by Labour, we have the Online Safety Act. I’m even prepared to believe the legislation was intended in good faith. I know, though, it was envisaged by politicians with the same knowledge of technology as the half-witted chief constable who thought I could magically remove Tweets.

The online safety act has led to people being blocked from their Spotify accounts.

The ratchet only moves in one direction. And so, content potentially at odds with the Government’s worldview becomes subject to clumsy age verification protocols, or becomes unavailable to under-18s. Political content, for example (er, didn’t we just make the voting age 16?). News content. Unintended consequences abounds. Spotify. Reddit pages about beer, for the sake of fuck.

Meanwhile, every teenager is downloading VPNs and laughing. Peter Kyle’s response? Dithering over whether to ‘do something’ about VPNs.

It’s okay though. Civil servants are scouring the Internet, discovering shockingly plebian attitudes of the kind you’ll hear in any pub, bar or cafe anywhere outside the M25. ‘Minister, the plebs are restless. They think there’s a crisis. They think your immigration policy is a joke. In fact, we even predict fisticuffs.’

‘I know,’ says the Minister. ‘Switch off the Internet!’

Yes, that’ll ‘Smash the Gangs’, won’t it?

Loading recommendations…