Negotiations after the shutdown sputtered out quickly. Republicans demanded that any extension create tougher abortion restrictions on Obamacare health plans, an expansion of the so-called Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal taxpayer funding of abortion. The ACA does not allow federal dollars to be used to pay for abortions directly, but neither does it prohibit plans in the marketplace from covering the procedure. Some states allow or even require federally subsidized Obamacare plans to cover it. Republicans and pro-life activists hoped to change that, Democrats refused, and negotiations fell apart.

So last Thursday, Senate Democrats announced that they would use the vote they were promised on a clean, three-year extension of the tax credits, mirroring a similar bill in the House supported by Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries. That’s unlikely to get the support it needs to overcome a filibuster from Republicans, some of whom would be persuadable to support a shorter extension, if it had an income cap and/or the abortion coverage restrictions. As expected, the GOP did not react well to the Democratic proposal. Senate Majority Whip John Barrasso said it was “not a serious offer.”

Democrats disagreed. When asked why he didn’t propose something Republicans would be more amenable to, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer told reporters Thursday, “The fault is there, not with us, and they can just vote for this, plain and simple.” Schumer also noted the GOP’s Hyde Amendment-related demands.

And yet there is no proposed Republican alternative. Speaker Mike Johnson insisted last week that “there will be a Republican response” to the health care issue, but none has yet materialized in the House, and President Donald Trump has offered little direction.

Approached by reporters in the Capitol, Rep. Vern Buchanan of Florida—who chairs the Health Subcommittee in the House Ways and Means Committee, which writes tax law—could not offer specifics on GOP fixes to the cost of health care. “We have to figure out a way to do this more efficiently, whatever that is,” he told reporters. “But we’ve got to get something done because it affects a lot of people.”

In the Senate, Sens. Bernie Moreno of Ohio, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, and Rick Scott of Florida have all proposed health care plans, but the party has not embraced any of them. Majority Leader John Thune did, however, praise Cassidy’s plan, which the Louisiana senator introduced with Sen. Mike Crapo, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, which has jurisdiction over Medicaid and tax law. Cassidy’s plan would let the enhanced subsidies expire and redirect that money into pre-funded health savings accounts tied to lower-premium ACA bronze plans.

A bipartisan group of 35 centrist House members—20 Democrats and 15 Republicans—has proposed a framework that would extend the tax credits by two years, paired with income caps and measures to target potential fraud in the program, but neither party’s leadership has taken it up.

Schumer seemed unfamiliar with the plan when asked about it at his Thursday press conference, and Jeffries likewise underestimated the number of members supporting the framework at a separate press conference the same day, saying it had fewer than 10 proponents, when it actually has almost three dozen. Jeffries contrasted its support with the 214 members, all Democrats, who have signed a “discharge petition” that would force a vote in the House on a three-year extension if it gets 218 signees.

“We’re open to having good faith discussions with any House Republican who’s serious about extending the Affordable Care Act tax credits, but the House Republican leadership is not,” Jeffries said. “They’ve repeatedly said they have no interest in addressing the Affordable Care Act tax credit issue.”

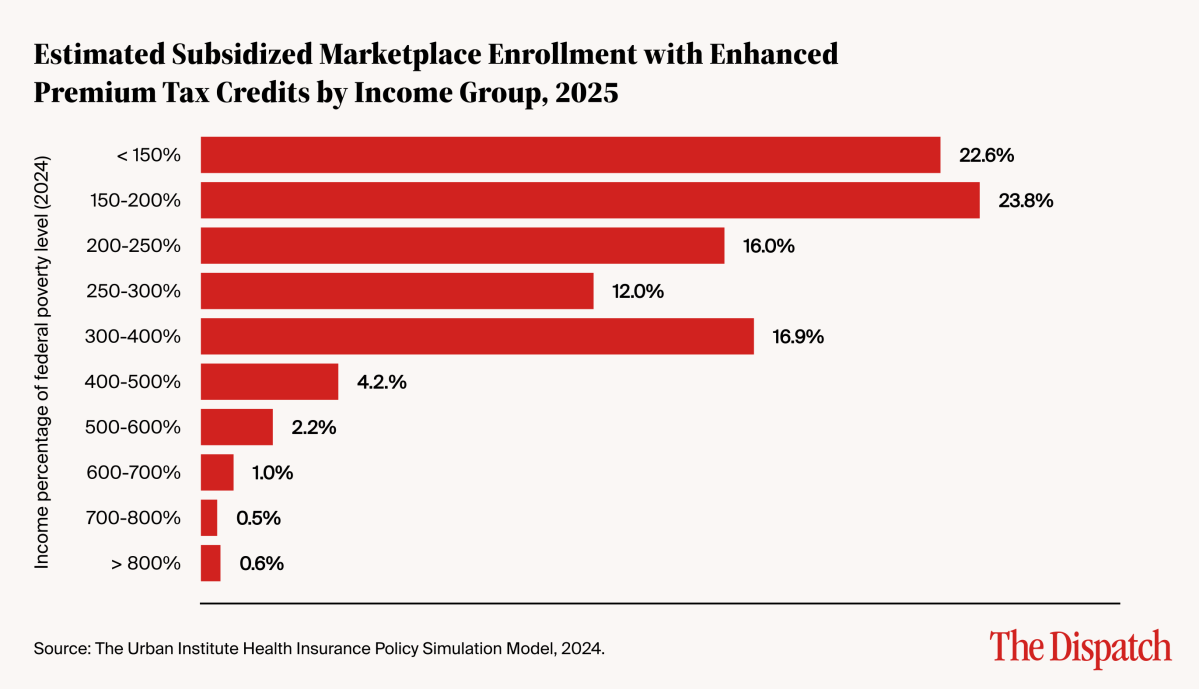

About 22 million people benefit from these tax credits, and they don’t represent the poorest of the poor or the richest of the rich. Before 2021, you were no longer eligible for subsidies under the ACA if your income was 400 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL)—$128,600 for a family of four. Democrats’ expansion that year allowed people above that income level to qualify for the subsidies and increased support for those who were already eligible.

Data showing where tax credit beneficiaries fall on the income spectrum are hard to come by, but the left-leaning Urban Institute released a projection in September 2024 of what that breakdown would look like this year. About 62 percent of beneficiaries had incomes at or below 250 percent FPL—$80,375 for a family of four—and only 8.5 percent had incomes at or above 400 percent FPL.

“When those enhanced premium tax credits expire at the end of this year, the levels will revert back to the original levels, which means that individuals with those incomes above 400 percent of poverty will no longer be eligible for that premium subsidy,” Lisa Harootunian, managing director of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s health program, told TMD. “And then those with those incomes below 400 percent of poverty will see less generous premium support.”

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that a typical family of four making about 404 percent FPL—or $130,000—would see premiums rise by more than $1,000 per month. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget puts the increase for families making 250 percent FPL at about $300 more a month. But extending the enhanced subsidies in full would cost $60 billion for just two years, or $350 billion over a decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

“It’s important that Republicans and Democrats work together on durable, bipartisan reforms that are going to address those drivers of high health care prices across sectors that are driving up premiums every year and impacting affordability and access to coverage,” said Harootunian.

Lawmakers may pull something together before they leave for Christmas recess on December 19. But it’s not looking likely.