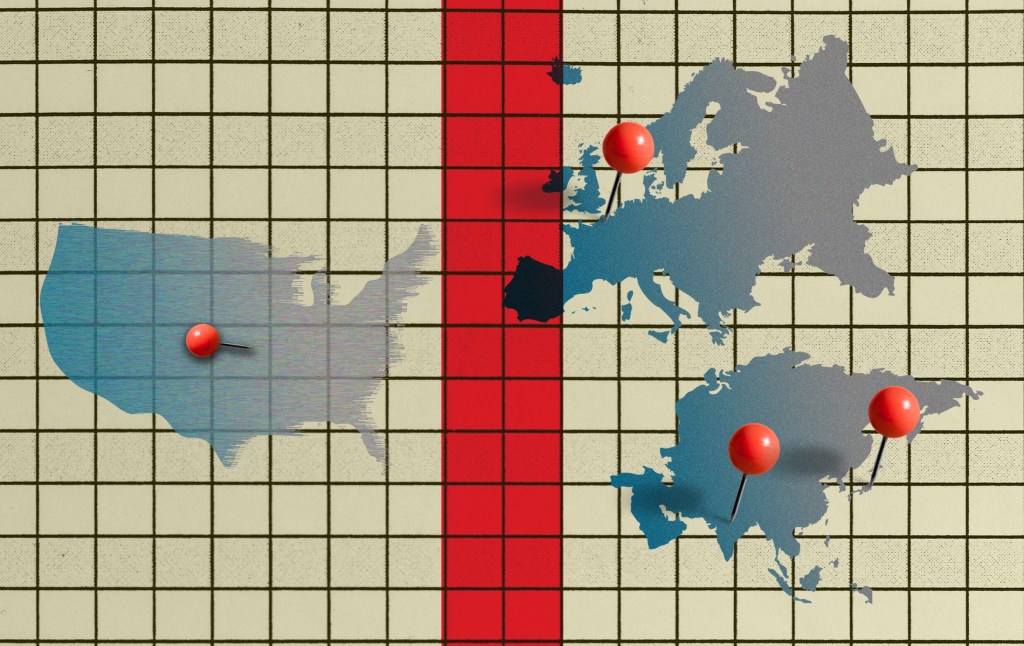

Since the end of World War II, the international system has been held together by American global leadership, rooted in an open economic order, a forward-deployed military, and a commitment to international liberal democracy. President Donald Trump has upended these pillars through a new tariff regime, open threats of allied abandonment, and a retreat from global democracy promotion. As U.S. foreign policy shifts toward protectionism, pulling back from overseas military commitments, and transactional diplomacy, the global system is transitioning away from reliance on American leadership. In response, U.S. allies in Europe and the Indo-Pacific are forging stronger regional blocs to pursue shared interests, bolster collective defense, and hedge against the instability of American politics. The result is a world that is no longer unipolar and not simply evolving into U.S.-China bipolarity, but one becoming multipolar—with emerging centers of gravity in Europe, China, the Indo-Pacific, and the United States itself.

A bipartisan retreat from global leadership.

While Donald Trump recently accelerated the shift away from U.S.-centered leadership with rhetorical force and policy disruption, the underlying transformation predates his second term and now spans both major parties. Both Republicans and Democrats are facing growing pressure from their bases to abandon the foundations of American primacy. On security, both the progressive left and the MAGA right support limiting the scope of U.S. military involvement in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, albeit with different motivations. Progressives frame it as “saving the world from the United States,” while MAGA Republicans describe it as “saving the United States from the world.”

Both impulses are fueled by frustration over decades of Middle East wars and the high costs of a forward-deployed military posture. These two political bases exert outsized influence through America’s primary system, which amplifies activist energy over broad public consensus. And while most Americans still express general support for a traditional leadership role abroad, the policy agenda is increasingly shaped by those who don’t. The result is a bipartisan, bottom-up recalibration of U.S. foreign policy—one that has shaken allied confidence and accelerated efforts to hedge against an increasingly unpredictable Washington.

Toward a European power center.

Trump’s hesitancy to continue arming Ukraine, aggressive tariffs on European allies, and repeated threats to withdraw from or abandon the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have forced the continent to rethink its relationship with the United States—and to coordinate more closely to compete with larger global powers.

Notably, the European Union itself has stepped up to play champion. The European Commission, which runs the confederation of European states, has decided to be more activist in determining the continent’s future. A recent EU defense strategy document illustrates Europe’s strategic shift: “The political equilibrium that emerged from the end of the Second World War and then the conclusion of the Cold War has been severely disrupted. … A new international order will be formed in the second half of this decade and beyond. Unless we shape this order—in both our region and beyond—we will be passive recipients of the outcome of this period.” The white paper outlines how the EU will invest more than $150 billion into European defense companies to disentangle its fragmented defense industrial base, a clear sign that Europe is moving away from relying on American arms.

Amid growing uncertainty about the credibility of U.S. extended nuclear deterrence, Polish officials have proposed hosting French nuclear weapons—a move that France has signaled it may support by broadening its nuclear umbrella to cover more of Europe. Additionally, fear of U.S. abandonment has also forced a United Kingdom-EU rapprochement on trade and defense cooperation after a decade of strained relationships from the Brexit fallout.

Europe’s economic posture is evolving in parallel. In response to Trump-era tariffs—and the threat of more to come—Brussels has prepared counter-tariffs and accelerated efforts to diversify trade ties away from the United States. New trade deals, such as the EU’s trade negotiations with India, are part of this effort. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen underscored this realignment recently, emphasizing Europe’s focus on “engaging with countries that account for 87% of global trade and share our commitment to a free and open exchange of goods, services, and ideas.” The EU plans to negotiate an unprecedented amount of trade deals.

For decades, Europe anchored its foreign and economic policy in transatlantic partnership, following the U.S. lead on security and trade. But the Trump administration’s aggressive tariffs, wavering support for Ukraine, and open threats to undermine NATO have pushed European leaders to fundamentally rethink that relationship. Europe is not abandoning the United States. But it is building a future where it no longer depends on Washington. In doing so, it is steadily emerging as a standalone power bloc—capable of advancing its interests independently of, and at times in defiance of, American leadership.

Minilateral momentum.

Trends in the Indo-Pacific mirror those in Europe but unfold with unique regional dynamics. Countries across the Indo-Pacific, from established allies like Japan and South Korea to rising partners like India, have been targeted by punitive tariffs and face renewed threats of U.S. military withdrawal unless they significantly ramp up defense spending. Although the administration has declared the Indo-Pacific—and competition with China—a top priority, the pivot has been sluggish, while threats toward allies have come swiftly, prompting doubts about American resolve. In response, Indo-Pacific countries are increasingly banding together to hedge against the risk of U.S. abandonment. Unlike Europe, where shared geography and institutions support large formal structures like the EU and NATO, the Indo-Pacific’s diversity and scale have led to a preference for nimble, interest-based “minilateral” coalitions—small groupings that enable coordination without requiring formal alliance commitments. These coalitions enable Indo-Pacific states to pursue shared security, economic, and technological goals—often in coordination with the United States, but with growing emphasis on intraregional cooperation rather than reliance on Washington.

Japan has emerged as the region’s strategic convener. Indeed, the very concept of the “Indo-Pacific”—now a fixture in U.S. foreign policy—originated not in Washington but in Tokyo, championed by former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), comprising the United States, Japan, India, and Australia, was likewise a Japanese initiative, first launched in 2007 and later revived in response to China’s growing assertiveness. Though informal and nonbinding, the Quad reflects the Indo-Pacific’s pragmatic approach to coalition-building: flexible, interest-driven, and resilient to political change. Similar to how European states initiated NATO in the 1940s, Japan uses minilateral coalitions to keep the Americans in, the Chinese out, and the North Koreans down.

Other coalitions have followed. The AUKUS pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States aims to build long-term military interoperability, particularly through nuclear-powered submarines and emerging technologies. Japan has also deepened its security ties with the Philippines, including trilateral dialogues involving the United States and Australia. In Southeast Asia, these groupings are expanding in scope—from joint exercises and maritime domain awareness to coordination on potential Taiwan contingencies. Meanwhile, India, historically cautious about alliances, has embraced minilateralism as a tool for balancing Chinese influence while preserving strategic autonomy. Trilateral groupings like India-Japan-Australia and security initiatives like India’s Africa-India Key Maritime Engagement (AIKEYME) exemplify this approach.

Taken together, these coalitions represent a quiet but significant reordering. They are not aimed at replacing the United States, but at reducing overdependence on its leadership. They give Indo-Pacific states agency in shaping regional order and resilience against both Chinese aggression and American unpredictability. While Washington remains a central node in many of these efforts, the strategic momentum is increasingly coming from within the region itself.

Multipolar ordering.

The regional blocs reflect a growing recognition that Washington can no longer be counted on as a stable guarantor of the liberal international order. Yet these shifts are still in their early stages—and they are reversible. The United States remains an indispensable power: No other nation possesses the same combination of military reach, economic scale, and alliance networks. U.S. allies are not seeking to replace Washington, but to protect themselves from its volatility. If America recommits to consistent leadership—backed by credible security guarantees, renewed economic engagement, and reciprocal partnership—it can remain at the center of the emerging order. But if it continues down a path of transactional diplomacy and strategic ambivalence, it risks being sidelined—not only by adversaries, but by its closest friends. The multipolar world is taking shape; whether the United States shapes it from within or watches from the margins will depend on how it chooses to lead.