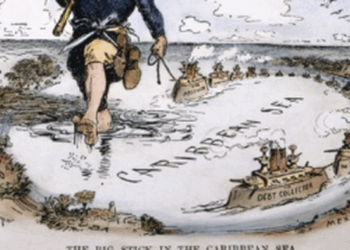

The United States Constitution establishes a republic, not a monarchy. If an American president ever had royalist or autocratic aspirations, it would pose an existential threat to the Constitution. Numerous Americans believe that’s what made President Richard Nixon so dangerous. When House Speaker Carl Albert denounced Nixon’s “one‐man rule” in 1973, he was channeling the opinion of many at the time—and since. But removing a monarch from office is no smooth, straightforward affair. If it’s true that Nixon acted like a king, then the closest the country has ever come to regicide was the drama of Watergate. The scandal began with the arrest on June 17, 1972 of five men working for the Republican Committee for the Re-Election of the President (CRP), who were caught breaking into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate Office Building. The scandal appeared to end with Nixon’s resignation speech two years later, on August 8, 1974. The successful removal of the president took presidential authority down in its wake, condemning any president who tries to recover it as another Nixon, another monarch-in-the-making. This has itself become a scandal, a stumbling block to understanding some of the most tumultuous years in American history, when the country and its politics changed forever.

As Edmund Burke understood, regicides