I have little doubt that die-hard critics of Elon Musk will find fresh evidence for their antipathy in a New York Times investigation of SpaceX. The newspaper reports that the rocket company has likely paid little or no federal income taxes since its 2002 founding, despite pulling in billions from US government contracts. Internal documents show the company had nearly $5.4 billion in accumulated losses by late 2021, giving it a powerful shield against future tax bills. A 2017 Trump-era change scrapped the 20-year limit on such loss carryforwards, letting SpaceX apply a big chunk almost indefinitely.

Now the NYT does note that the tax strategy is legal, but critics will surely counter that legality only makes the case for a change in the law. They will also likely note, as the NYT does, that federal contracts made up nearly 84 percent of SpaceX revenue, and commercial ventures like Starlink are now booming. For Musk detractors, it’s a case study in how high-profile firms can profit from public money while keeping the IRS at bay.

Debating whether SpaceX and similar firms should face higher tax bills in some fashion is hardly unreasonable. Yet that narrow, green-eyeshade framing risks missing the bigger picture. An important way taxpayers should assess the return on such public spending, like SpaceX contracts, is not merely in corporate tax receipts or even the immediate value of services provided—like transporting NASA astronauts to the International Space Station—but in the economic, technological, and strategic benefits these ventures generate.

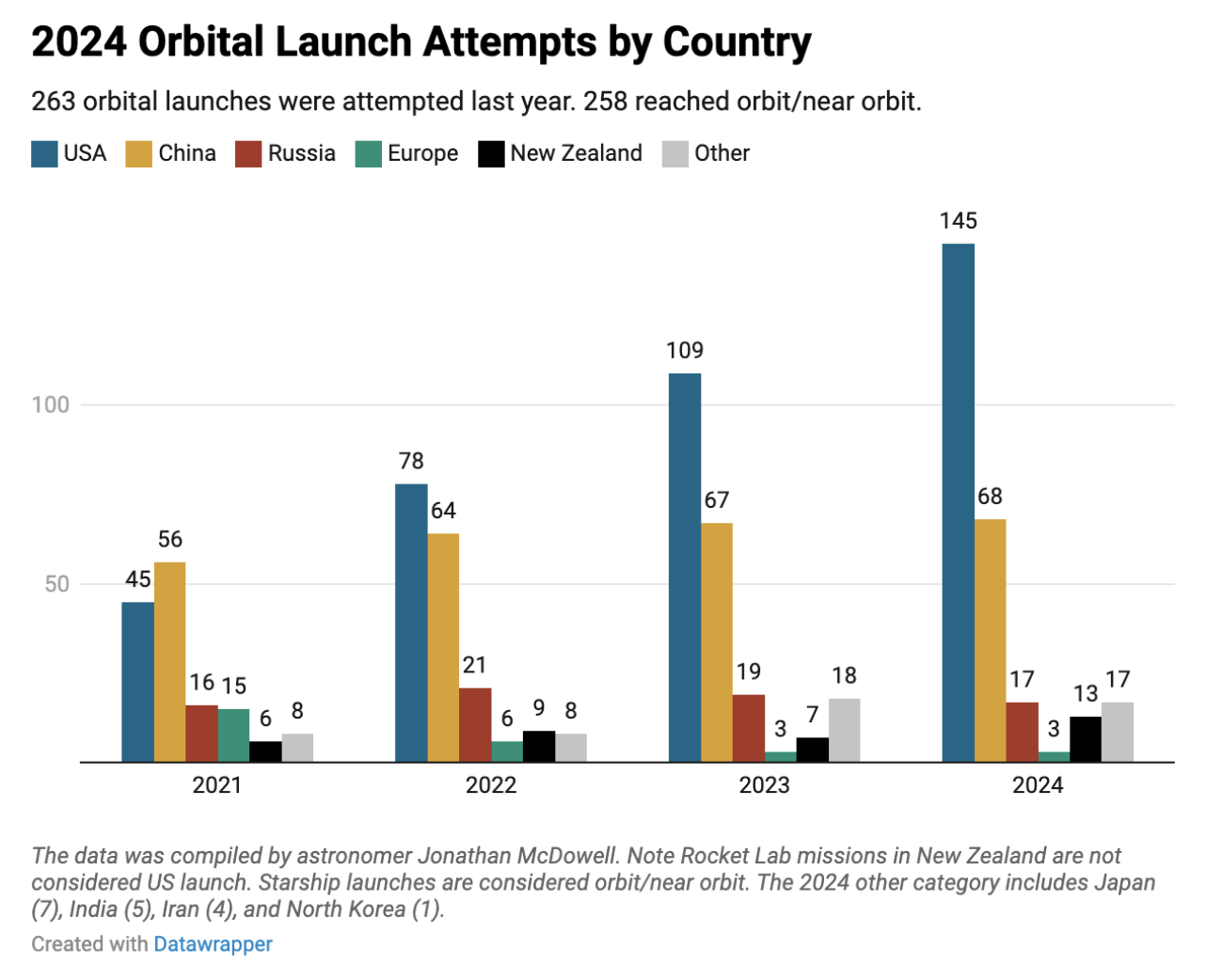

SpaceX’s advances in reusability have already slashed launch costs nearly 30-fold from Space Shuttle levels, making access to space vastly cheaper and more frequent—and opening the door to seemingly sci-fi industries like city-to-city rocket transport, asteroid mining, and space-based solar power. SpaceX is why America looks dominant in this chart of space launches:

What’s more, its massive and growing Starlink satellite network promises to deliver high-speed internet to remote corners of the globe, shrinking the digital divide and enabling economic growth in underserved areas. On the strategic front, the company’s capabilities strengthen American military readiness and secure independent access to orbit, critical in a new era of great-power, off-planet competition.

For me, the knee-jerk framing of this issue might well echo an earlier policy skirmish. In 2019, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez argued at a congressional hearing that taxpayer-funded federal research acted as early-stage venture capital for drug development, yet yielded “no return” when private firms commercialized the results. In a WSJ op-ed, Safi Bahcall, a physicist and former biotech CEO, correctly countered that the postwar US model deliberately prioritizes rapid transfer of government-backed research to private industry, because the public’s return comes indirectly—through GDP growth, job creation, technological leadership, and national security—rather than via royalties or licensing fees.

Musk’s critics may be making the same analytical misstep. Whatever one thinks about the fairness of SpaceX’s aggressive tax strategy, the richest dividend from the billions in public contracts may not appear on an IRS ledger. It may instead be found in the capabilities left behind—lower-cost space access, global connectivity, scientific breakthroughs, and a stronger strategic position for the United States. Those, arguably, are the real returns on investment.

The post The Ultimate ROI of SpaceX Is Tech Progress, Not Tax Payments appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.