The moves technically aren’t “socialism” either, as that system typically features complete government ownership and control of companies or industries and the (supposed) redistribution of these shared resources based on need. We’re not really doing that either—the government isn’t the only, or even majority, owner of the targeted companies, and the public is getting at best a slice of what the firms generate. (Those with political connections, on the other hand, appear to be doing better.). Both socialism and capitalism also come with lots of needless political and historical baggage that urges me to avoid those loaded words.

“State corporatism,” by contrast, indicates the close relationship between the government and these companies yet distinguishes it from capitalism and socialism and avoids all the baggage. So, I’ll go with that for now but freely admit that the proper term for this stuff isn’t entirely clear.

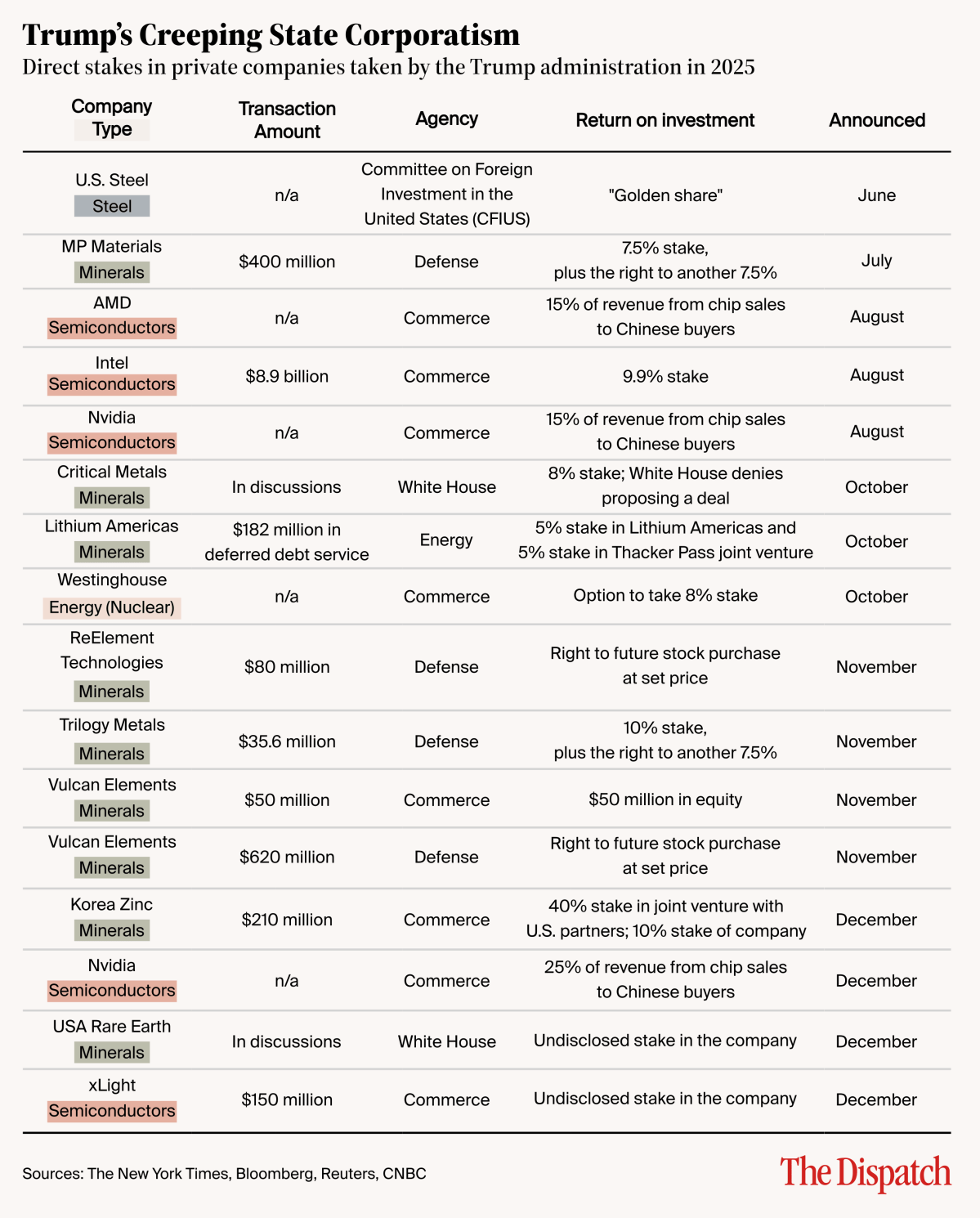

What is clear, as my Cato colleague Tad DeHaven just detailed last week for The Dispatch, is that what started over the summer as a state corporatist trickle has since turned into a gusher. Following the U.S. Steel “golden share”—which gives the administration control over the company’s business decisions but no direct financial stake–-in June and the Intel deal in August, the Trump administration has inked deals for permanent and direct equity stakes in eight other companies across several different industries, with more deals reportedly in the works. Several of these transactions have made the federal government a firm’s largest shareholder and, like Intel, include options for an even greater share of government ownership in the future. Meanwhile, Trump has announced new arrangements with Nvidia and other U.S. semiconductor firms, whereby Uncle Sam will lift export controls (which ostensibly exist to protect U.S. national security!) on advanced semiconductors in exchange for a significant cut of the chipmaker’s sales in China. Here’s a breakdown of what we’ve seen so far:

As we discussed with respect to Intel, Trump’s “state corporatism” push is unprecedented in several important ways. The U.S. government has a long history of supporting domestic companies with nonmarket interventions like tariffs, subsidies, and procurement preferences, but these measures are offered broadly, provided at arm’s length, and authorized by law. They’re also relatively insulated from ongoing government involvement and oversight: Washington doesn’t interest itself in a firm’s public share price or day-to-day business—sales, purchases, factory locations, etc.—beyond (perhaps) ensuring that the company complies with terms of a government contract or subsidy agreement. Trump’s state corporatism fundamentally differs from these policies, in that it empowers (if not requires) the government to be involved in a specific company’s routine operations and to care deeply about the firm’s ultimate success or failure.

As Georgetown’s Peter Harrell has explained, moreover, another distinguishing factor here is that the executive branch is acting pursuant to dubious (at best) legal authority with respect to these transactions:

[T]he government appears to be relying on the fact that while almost no statutes expressly authorize the government to take equity stakes in companies as part of a grant, contract, or regulatory process, the government can interpret broad language in a number of statutes as permitting the government to do so.

In other words, the Trump administration is simply assuming the power to invest American tax dollars in private domestic firms—or to otherwise take a cut of those firms—because no law expressly says it can’t. (And, I should add, because no one has thus far emerged to stop them.) You don’t have to be a constitutional scholar to know that’s not how American capitalism and government are supposed to work, but … here we are.

As Harrell goes on to explain, Trump’s state corporatism is also radically different from the rare instances in which the government has taken an ownership stake in a U.S.-based company (or a warrant to take such a stake in the future). For one thing, those arrangements (e.g., the bank and auto bailouts during the Great Recession) always came in response to a genuine economic or foreign policy emergency—financial crisis, pandemic, wartime, etc.—that simply doesn’t exist today. Those deals also were authorized by law and were expressly temporary, with the government’s divestment from systemically important firms (banks, automakers, airlines, etc) conditioned upon the achievement of stated objectives (e.g., the company returning to solvency).

State corporatism, by contrast, consists of repeated, open-ended, non-crisis interventions in many different private entities, none of which are on the verge of collapse and begging the government to save them (or of taking down the entire U.S. economy). In several cases, in fact, companies today have been pressured into granting the Trump administration a share of their business, lest they lose out on subsidies, private investments, or overseas sales.

These deals, in short, are unlike anything we’ve seen in the modern era—and by a large margin.

Yes, We Should Be Worried

As DeHaven detailed last week and as I explained in August with respect to the Intel deal, the federal government taking an active and ongoing stake in a private, commercial firm raises serious problems that are mostly lacking from other interventionist economic policies like tariffs or subsidies—and, of course, entirely lacking from open, neutral, lightly-regulated private capital markets.

Recent headlines, unfortunately, show that these problems are already popping up. In August, for example, I discussed how government investment in or control of a company could undermine its long-term viability by pushing the firm to undertake transactions and investments for political, not commercial reasons. Shortly thereafter, U.S. Steel reversed its decision to mothball an ancient, inefficient blast furnace in Granite City, Illinois, as part of parent company Nippon Steel’s efforts to modernize U.S.-based facilities. A few calls from the golden share-wielding Trump administration, it appears, had pushed U.S. Steel to instead restart the decrepit plant, regardless of the economic (or environmental) implications. That’s surely good news for the Granite City plant, but it’s surely bad news for U.S. Steel and its notoriously lagging innovation and productivity.

Another emerging problem is that state corporatism will harm other U.S. companies that either compete against or need to do business with state-backed firms. As the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip reports, for example, businesses getting into bed with the Trump administration are able to “elicit better treatment—in their ability to sell to China, the tariffs they pay, how they are regulated, and what mergers are allowed”—than what their U.S. competitors get. Companies are also looking to do business with government champions, not because they make the best products but to get on Trump’s good side or to avoid his wrath. Following news of Nvidia’s surprising $5 billion deal to co-develop AI chips with state-backed Intel, for example, many analysts speculated that deal—chump change for the $4 trillion Nvidia but a move that made Intel’s stock pop—was primarily intended “to curry political favor with the president.” Shortly before and after the deal, Nvidia got Trump’s permission to sell AI chips to China (after giving Trump a cut, of course).

The broader risk of capital misallocation—private investment chasing government champions instead of solid performers or innovative startups—is also becoming apparent. Share prices for Intel, MP Materials, Lithium Americas, and Trilogy Metals have zoomed higher after the government announced its equity stakes, but they did so not because the companies’ fundamentals improved but simply because they had Uncle Sam’s backing. Meanwhile, Bloomberg reports, investors have started “trying to think like Trump to find the next targets of the US government’s ownership stakes in public companies, which tend to see massive gains following the investment.” That’s bad enough as it is, but the shift in U.S. investment strategy goes beyond just a few speculative bets:

Trump’s focus on industrial policy and his beliefs in government intervention and guiding the market are changing the way investors should evaluate companies, according to Aniket Shah, the global head of sustainability and transition strategy at Jefferies Financial Group Inc. who tracks the economic implications of Trump’s policies. “Part of this analysis of businesses going forward has to be this political relationship with the state,” he said.

Target companies’ share prices will benefit, of course, but they do so by sucking up finite capital that could have gone to productive, well-performing alternatives—including in the same industries. It’s textbook capital misallocation and, as we discussed regarding the costs of China’s industrial policies, it means lower productivity and growth—and a weaker U.S. economy in the long term.

Finally, there’s the clear precedent the summer’s interventions have set for more of this stuff in the future. Most immediately and obviously, the Intel and U.S. Steel arrangements were quickly followed by several copycat deals that have received much less coverage or concern. Other companies, the Journal’s Ip reports, have reluctantly hopped on the state corporatism bandwagon out of fear, self-preservation, or competitive opportunity. And, importantly, no one in Corporate America or the federal government has thus far mounted any real opposition.

Trump pushed the boundaries of U.S. government involvement in private businesses, markets mostly shrugged, and Congress did nothing. So, in typical Trump fashion, he just kept pushing, and there’s little reason to think that more of these deals aren’t coming in the months ahead. As long as private companies need federal government help—subsidies, procurement contracts, regulatory approvals, tax breaks, whatever—Trump will be ready to use that leverage for another state corporatist deal (and, in fact, is openly promising to do so). The only real question is whether the next president will take things even further, now that the precedent has been set and “emergency” guardrails have been removed.

Maybe this isn’t a worst-case scenario following the summer’s U.S. Steel and Intel arrangements, but it’s pretty darn close.

Why Are We Even Doing This?

Equally damning is the lack of a sound justification for any of these moves, even from supporters and especially given the availability of both market-based and nonmarket policy alternatives that have a long history of use and success in the United States. It’s widely understood, for example, that the biggest obstacles to domestic mining and refining of “rare earth” products aren’t a lack of government investment but instead onerous regulations and permitting timelines that both Republicans and Democrats have targeted for reform. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, moreover, there are a wide range of tax, trade, labor/immigration, education, and regulatory reforms that the U.S. government could implement to boost commercial firms producing semiconductors, minerals, metals, and other “critical” goods—no government shareholding needed.

Should market-based policies prove insufficient, the government could use subsidies, prizes, long-term procurement contracts, stockpiles, and other nonmarket measures that can tilt the playing field in domestic firms’ favor or otherwise achieve the government’s objectives. Many of these policies can raise their own economic and political concerns, of course, but they still come with lower costs and fewer risks than what Trump’s doing now.

There’s also the obvious question of whether any federal government support is needed in many of these cases, and minerals provide a timely example. As the Wall Street Journal just reported, U.S. startups “are offering up new solutions to China’s crackdown on critical mineral exports, propelled by record levels of private investment and advances in artificial intelligence.” Overall, venture capitalists this year have invested $600 million into U.S. critical-mineral firms—the highest level ever—and the largest private buyers of these products have expressed a strong willingness to pay more for non-China supplies so they can avoid potential bottlenecks. (“A slightly larger cost for the critical minerals to ensure that you don’t have to discuss it at the next board meeting is probably worth it,” one expert told the Journal.)

The day after the Journal report, a private, Utah-based company—one without Trump administration investment—announced that it had discovered “what it says may be the most significant critical mineral reserve in the U.S.” These rare earth and other minerals can be quickly tapped and processed at the company’s nearby facility because “[t]he Utah land is already permitted for mining … and the area benefits from having full infrastructure already in place over its 8,000 acres.” The company also claims that the extraction process will be more environmentally friendly than typical rare earth mining, and one local geologist posited that the Utah minerals find could set off a “gold rush” in the area.

Still other firms in the West are finding ways to reduce or eliminate their reliance on rare earth minerals altogether—also driven by concerns about China-related bottlenecks (and, of course, their desire to profit). Surely, not every national security issue can be solved by the world’s best capital market and good ol’ supply and demand, but many of them can—and the fixes often happen before Uncle Sam even gets his pants on.

And when asked why the government has suddenly embraced state corporatism so fully, the president’s answers are hardly reassuring:

Trump has pushed the government to make direct interventions in what it sees as critical segments of the economy, taking stakes in semiconductor and critical minerals companies. Asked if he is considering taking a stake in any defense companies, the president said “yes.”

“We should take stakes in companies when people need something. I think we should take stakes in companies. Now, some people would say that doesn’t sound very American. Actually, I think it is very American,” Trump said.

Summing It All Up

As Harrell documents, the federal government has avoided taking a direct stake in a healthy U.S. commercial enterprise since at least the 1950s. This year, it has taken 14, and more are undoubtedly on the way. Trump’s state corporatism represents a fundamental shift in not just U.S. policy but American capitalism itself. Sure, second-rate countries like China and France and Japan have done this kind of stuff in the past and continue to do it today. The United States hasn’t, and all that restraint has gotten us is a rich, dynamic, and innovative economy that’s still the envy of the world.

Now, we face a troubling future across multiple fronts. The problems and distortions associated with state corporatism—cronyism, favoritism, inefficiency, capital misallocation, etc.—will proliferate, often without notice. State champions will double down on their relationship with the government and the short-term advantage it provides. (Some, in fact, have already started.) There’s also a clear risk that more U.S. firms join with the government out of fear or necessity, and that future administrations will use this year’s precedents to implement their own versions of state corporatism—distorting more of the American economy along the way.

Even without that expansion, however, there’s the obvious problem of how to unwind what Trump has already put in place—especially as corporations shift to treat this aberrational period as the new normal. Lawsuits seem unlikely: The people with legal standing to challenge the new tie-ups in court—shareholders and managers of target firms—have no clear financial or political motivation to do so, and the legal basis for any such suit would be murky, at best. A future president could undo the deals, but that would require giving up executive power—something, unfortunately, that few modern presidents have entertained. That leaves reform in the hands of Congress, which could pass a law forcing divestiture or establishing guardrails on government involvement, but partisan acrimony and gridlock make that another longshot.

This year, in other words, could stick with us for a very long time.

Chart(s) of the Week