PONTIAC, Michigan—Traveling a fair amount for work outside of major metros requires relying on rental cars. And relying on rental cars quickly teaches you that while you might reserve a standard sedan every time, there is no reason to expect the rental car agency to actually give you the keys to a sedan when you show up at the counter.

Eventually, you realize your fate is entirely in the hands of the rental car gods, and the rental car gods are capricious gods.

Sometimes, the rental car gods frown upon you. This happened to me at the 2011 Iowa straw poll, when I ended up driving a Chevy Aveo across the entire state. If you don’t know what a Chevy Aveo is, consider yourself lucky. If you’ve had the misfortune to ride in one, you know that a go-kart is a smoother, roomier, and safer ride.

Sometimes, the rental car gods laugh at (or perhaps with) you, which is what happened to me in 2017 when I went to Alabama to cover the Senate campaign of Roy Moore, a notorious creep and alleged pervert. I was told at the rental car counter they couldn’t honor my reservation for a sedan, and the only vehicle available was a boxy full-size van. Pulling up to the first campaign event in the kind of van you’d half-expect to come with the words FREE CANDY scrawled in paint on its side, I was worried I’d be mistaken for a fan of Moore.

But sometimes the rental car gods smile upon you. This happened to me at the 2020 Iowa caucuses.

“Would a Dodge Challenger be okay?” the agent asked me in the Des Moines airport.

Why, yes, it would be okay.

I had, once before, ended up with a Dodge Charger, the modern sedan version of the two-door Challenger, while covering a special election in upstate New York and was instantly impressed.

I’m not a car guy, so I lack the expertise to explain to you on a technical level why the Dodge Challenger is the greatest car on the road today—the same way I can’t explain to you why Caravaggio’s The Calling of St. Matthew is the best painting ever painted or why Bernini’s David is the best sculpture ever sculpted. Each of these statements just seems to me to be self-evidently and objectively true. But I can tell you there is nothing quite like going from 0 to 60 in a Challenger. Over the course of four days and 469 miles in January 2020, I stuck to Iowa’s blessedly snow-free backroads whenever possible. Every stop sign was no longer an annoyance slowing me down from getting from Point A to Point B, but another opportunity to experience the thrill of putting the pedal to the metal in a Challenger.

While speeds can vary depending on the car’s trim, the most souped-up Challenger can go from 0 to 60 in 1.66 seconds—faster than the fastest Ferrari. My rental took more than 4 seconds to hit that mark, but there’s more than just its speed that makes the Challenger great. There’s the rumble and roar of the V8 HEMI engine that you can feel in your chest. There’s the beautiful sleek retro design straight out of 1970—the heyday of the classic American muscle car. You don’t have to take it from me—just listen to Jay Leno, the famous comedian and avid car collector, who wrote last year: “To me, the Challenger is really the last great American road car.”

I’ve driven more than 100 different cars in my life, including some nice ones, but the Challenger is really the only car I’ve ever loved. So when my wife’s work-from-home status was starting to end in 2021 and we owned only one car (a 2011 Hyundai Tucson), I told her I was interested in buying a used Challenger that I found online for $16,000 with 50,000 miles on it.

“You know your friends will laugh at you,” she said.

“Yes, I’ve considered this,” I replied, fully aware that someone typically dressed in Gap Outlet polos or Brooks Brothers dress shirts doesn’t exactly look like a muscle-car guy. “But there are much more expensive and destructive ways to have a midlife crisis.”

Ultimately, I gave into the practical reality that my wife, whose daily commute could push two hours roundtrip, needed a new car and that I, with a commute that is often one flight of stairs, did not. She got a Mazda, and I figured my midlife crisis could be postponed until our Hyundai gave up the ghost.

But then, tragedy struck: Dodge announced that 2023 would be the last year it would produce the Challenger and the Charger. Then Chevy killed off the Camaro. The last muscle car left in production was the Ford Mustang. But even with the market all to itself, Mustang sales dropped 31 percent in the first quarter of 2025.

Why does the American muscle car seem to be dying off? What, if anything, is America losing as it fades away? I set out to answer these questions after The Dispatch’s editors encouraged us writers to expand our horizons beyond the typical political fare (see Mike Warren on Tiki culture, for example). I decided that if I couldn’t own a muscle car, at least I could write about it. And that’s how I ended up in Pontiac, Michigan, earlier this month inhaling the smoke of burning rubber and talking to muscle-car enthusiasts.

That distinct smell of burning rubber is the first thing you notice when approaching the venue at Roadkill Nights. Woodward Avenue has been closed down for a day of legal drag-racing, and hot rods are doing burnouts for improved traction just before they make their trial runs.

Those who drove in but aren’t competing have their cars lined up on the street outside. I’m greeted by an array of Challengers—purple, neon green, orange, metallic blue. But the whole scene looks more like a county fair for car enthusiasts than a shot out of Fast & Furious. There are families and food trucks, but instead of the Tilt-a-Whirl and Loop-o-Plane, event-goers wait in long lines for hired drivers to take them on drift rides—in which the driver takes such sharp turns that the car’s rear tires screech and slide sideways. For little kids, some barely old enough to walk, there are Power Wheels-style muscle cars nearby to drive. A full-size monster truck does donuts in a parking lot for entertainment, but the main show for the thousands of attendees is the drag racing.

The first person I talk to on the bleachers overlooking the races that day is Mike Sherrow of Suffolk, Virginia, who has attended the event 10 years in a row. Like many of the enthusiasts I spoke to, Sherrow’s love of muscle cars was inherited from his father. “Lego started it for me, and then building my dad’s ‘65 Chevy truck,” Sherrow told me. “It was like the family hot rod.”

Asked what he loves about muscle cars now, Sherrow points to the creativity in modifying the vehicles with one’s own hands and tools: “Building your own stuff, and taking somebody’s car and modifying it to make it what you want. It’s just a part of car culture. And it’s going away. This [event] is keeping it alive.”

Sherrow attributes the decline of muscle-car culture to a variety of factors. “Being sued by the EPA for emissions control laws, outlawing even street-legal racing, closing down racetracks because people are building houses too close. It’s a dying art,” he said. “The greats that did it, they’re passing on, and their knowledge is going away with it.”

To understand the decline of the American muscle car, it helps to first remember that it has died—and been resurrected—before.

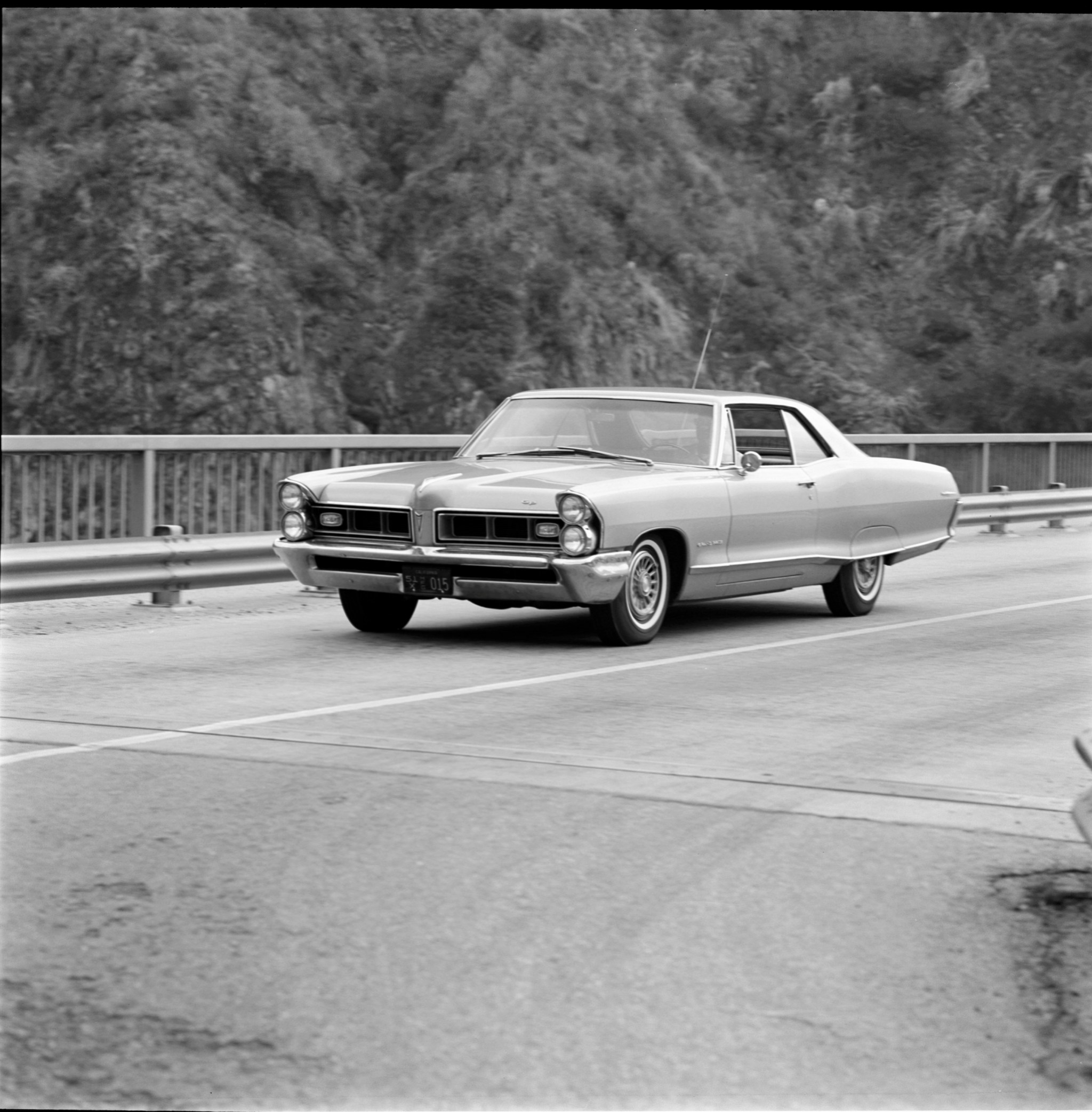

The original muscle car era began, in most tellings, in 1964 with the production of the Pontiac GTO. Competitors—including the Ford Mustang, Plymouth Barracuda, Dodge Charger and Challenger, Chevrolet Camaro and Chevelle—soon appeared on the scene. While sports cars can be foreign or domestic, muscle cars by definition must be American-made, with a powerful engine in a lightweight body. Though there’s some debate about what separates muscle cars from domestic sports cars, muscle cars also prioritize straight-line speed over handling and agility and have that, well, know-it-when-you-see-it muscular look (which is why many don’t consider the sporty Corvette to be a muscle car).

It is no coincidence that the muscle-car era began when the oldest baby boomers turned 18. In 1963, Tom Wolfe chronicled the custom-car craze gripping teenagers in America in an 11,000-word article for Esquire magazine titled, “There Goes (VAROOM! VAROOM!) That Kandy Kolored (THPHHHHHH!) Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (RAHGHHHH!) Around the Bend (BRUMMMMMMMMMMMMMMMM…).”

“Thousands of kids are getting hold of cars and either hopping them up for speed or customizing them to some extent, usually a little of both,” Wolfe wrote. “Even the kids who aren’t full-time car nuts themselves will be influenced by which car is considered ‘boss.’”

This phenomenon was a direct result of America’s post-war economic boom. “The war created money,” Wolfe wrote in the introduction to his 1965 collection of essays, titled after his Esquire essay. “It made massive infusions of money into every level of society. Suddenly classes of people whose styles of life had been practically invisible had the money to build monuments to their own styles.”

Where others saw the gaudy or even garish tastes on display in custom cars as unworthy of a second thought, Wolfe saw baroque art objects worthy of study. He presciently predicted in 1963 that car manufacturers in Detroit “may well be on their way to routinizing the charisma” of the custom car. Indeed, within the first two years of production, Ford had sold 1 million Mustangs—before Ford race cars made history in 1966 by beating Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

But by the time Brue Springsteen was singing about muscle cars in “Born to Run” (the album of the same name was released 50 years ago this week)—“Beyond the Palace, hemi-powered drones scream down the boulevard/ Girls comb their hair in rearview mirrors and the boys try to look so hard”—the muscle car era had largely come to a close. Production stopped on the Challenger and Charger, respectively, in 1974 and 1978. The first-generation Mustang stopped being produced in 1973 (but different iterations were available, leaving it the only muscle car in continuous production since its birth).

The end of the golden era of the muscle car is simultaneously attributed to environmental regulations like the Clean Air Act of 1970 and that decade’s oil crisis that made gas-guzzling muscle cars too expensive for most consumers. The baby boomers were, of course, growing up and starting to have babies of their own and seeking more practical vehicles for their families.

Now, history appears to be rhyming. Since the end of the golden era, the muscle car has experienced revivals, the most recent of which began in the aughts, perhaps not coincidentally after the The Fast and the Furious franchise launched in 2001, in which Vin Diesel’s character drives a 1970 Dodge Charger. The movie and its sequels became the highest-grossing franchise of all time for Universal Pictures, and in 2006 Dodge reintroduced the Charger and the Challenger in 2008, selling more than 2 million of the vehicles combined before Dodge recently stopped production.

If you talk to car enthusiasts, the proximate cause of the recent untimely demise of the Challenger, Charger, and Camaro was increasingly onerous fleet-wide emissions standards, and there’s a lot of truth to that. Those regulations meant that it wasn’t enough for Dodge to simply slap gas-guzzler taxes on the vehicles and purchase offsets from Tesla through a cap-and-trade system to maintain production in the face of billions of dollars of potential fines. It would have made little economic sense to discontinue the vehicles without regulatory pressure: Dodge was selling nearly 80,000 Chargers and more than 50,000 Challengers a year when it announced in 2021 it would discontinue the models and would instead offer a new electric replacement—the Dodge Charger Daytona EV. This model sold just 4,299 units in the first half of 2025—its first and potentially only year on the market. Few muscle car enthusiasts were interested in an electric vehicle that replaced the rumble and roar of the V8 engine with speakers and chambers designed to mimic the sound of a gas-powered engine. “Pretty lame,” declared a review in Edmunds. Following the loosening of emissions standards this year, Dodge announced it would be bringing back a gas-powered Charger (but not the Challenger) in 2026 with a V6 engine, not the classic V8.

Jose Pretel, a real-estate photographer and official brand ambassador for Dodge from South Florida who posts photos of his Dodge Charger Hellcat on Instagram (handle @onebadhellcat), acknowledged the challenges the brand has faced but offered an optimistic take at Roadkill Nights in Michigan. “I think some people in the community are skeptical of the changes, right? We went full electric. Now we’re back to a twin turbo, smaller motor than before. They’re kind of wondering: ‘What are they doing?’” Pretel told me. “I actually think this motor is going to last longer, be able to take more abuse … [and] be just as popular in a few years.”

That, of course, remains to be seen. The environmental regulations that killed off the Challenger and Charger in 2023 are not the entire story behind the decline of the modern muscle car. High interest rates and prices—driven in part by tariffs—plus a declining percentage of young people having driver’s licenses and changing consumer preferences all play a role. The reintroduced gas-powered Charger—even if it brings back the V8 engine—could face the same headwinds in 2026 that the Mustang experienced this year that led to a big drop in sales.

To some, the death of the muscle car would simply be a good thing: They’re loud, gaudy, and (marginally) harm the environment by burning more fossil fuel per mile driven than other vehicles. But to others, they are objects of beauty, outlets for creativity and innovation, and sources of fun, as well as camaraderie.

In speaking to attendees at Roadkill Nights, it quickly became clear that a love of cars isn’t merely about the vehicles themselves; it’s also a way to build and maintain friendships. Shawn Splaney from Flint, Michigan, who attended the event with two friends, told me he owns a ‘68 Mercury Cougar that’s “a basket case” not yet in driving condition and the ‘91 Mustang he typically drives is a labor of love. “I’d rather have the older stuff,” Splaney said. “My Mustang is manual steering, manual valve body, where you have to shift the transmission—you have to drive the car. That’s what I like.”

“It’s my Number One hobby,” he continued. “We have garage time. It’s just a time to hang out with the guys, or girls, and it’s relaxing. It’s fun. Even though you’re struggling with trying to overcome problems at times … you’re just talking, you’re venting, it’s therapeutic.”

As a non-car-guy interested in becoming one, I’m curious to what extent this hobby, like some other male-dominated hobbies, is largely an excuse for drinking beer. “We’re not heavy drinkers,” Splaney told me, but “sometimes there’s a victory: ‘Hey, let’s go to the bar and kind of show off what we did.’ Sometimes there’s that agony of defeat where you’re like, ‘Hey, maybe I do need a beer because the car’s not fixed yet.’”

Many but not all in attendance are doubtful that car culture can be built up around electric vehicles. Lincoln Brousseau of Grand Blanc, Michigan—a friend of Splaney’s for 15 years since they first met via an online car forum—thinks maybe it’ll catch on with the younger crowd once the proper recharging infrastructure is in place. But the third friend in the group, Brooke Rennert, a 21-year-old from Rochester Hills putting herself through welding school by working as the only woman at her oil-change job, isn’t having any of it. “I don’t like electric cars. I like the sound of a heavy engine. I like the power,” she said. “An electric vehicle has power, but in a different way. It’s not like a big V8, big-block sound.”

For car enthusiasts who like tinkering or hopping up their engines, there’s little interest in electric vehicles. “There’s nothing there to change. You’ve got batteries and a motor,” said Jim Schmittinger from Slinger, Wisconsin, who works on EVs in his job for a Honda dealer.

“Building your own stuff, and taking somebody’s car and modifying it to make it what you want. It’s just a part of car culture. And it’s going away.”

Mike Sherrow

Schmittinger estimates he’s poured $100,000 into the engine of the Buick GNX he’s racing that day, and he said money is one big problem with car culture: “People will spend money they don’t have to compete with somebody they don’t know.” But the worst trend, he said, is that social media has changed the culture for the worse: “It’s not about the cars and getting together with people anymore. It’s about how many likes I get on YouTube or Facebook.”

Asked for practical advice about how a non-car-guy like myself might become one, Schmittinger simply said: “Start saving your money.” Others tell me the first step is simply getting a car that you love. “Find a car that you actually are enthusiastic about that you want to have and keep,” Splaney said. “Start learning here and there the small stuff, whether it’s just doing oil changes, and just keep pushing that up. We all started somewhere.”

Rennert, the young woman putting herself through welding school, had some advice for other ladies looking to become car gals: “Make sure you’re in a group of people who respect you. It’s kind of hard sometimes, but you can do it just the same as any guy can do. Meet people. Don’t be afraid not to know anything. Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Do your research. Find a vehicle that really interests you, and go from there.”

As I’m getting ready to leave Pontiac, I’m left wondering, if I ever get around to buying a Challenger, just how expensive and just how old it might be. But, as Schmittinger listened to a friend of his bemoan the demise of the Challenger, he piped up with a prediction: “It’ll be back.”