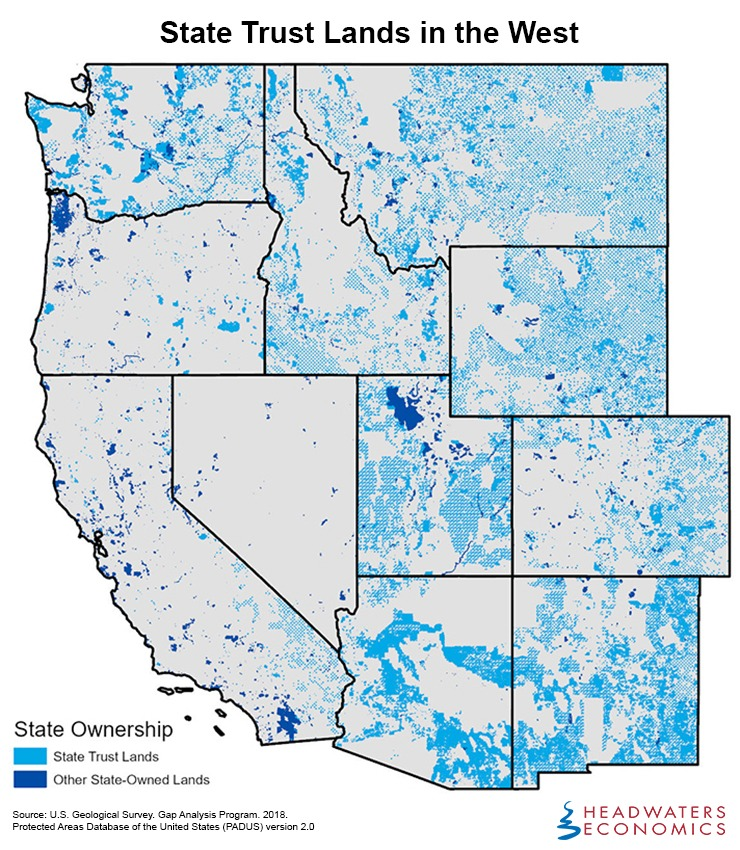

A land ownership checkerboard exists in nearly every state because of an oddity called “state school trust lands.” The federal government granted those lands at the time of statehood, under the Land Ordinance of 1785. Thomas Jefferson’s system divides and records land into townships, each with 36 one-square-mile sections. New states entering the union were each given 2 sections per township, to be held in trust to fund public schools.

State Land Boards were created to manage those lands – in my state of Colorado it’s 4 million acres. The Board was charged with administering the lands “in such a manner as will secure the maximum possible amount” for the school fund. The Lincoln Institute of Public Lands explains, “That singularity of purpose continues today and distinguishes state trust lands… from other types of public lands.” In other words, these lands are for making money to fund schools.

State lands generate revenue in many ways, primarily through leases for farming, grazing, mining, oil and gas, renewable energy, and research. Some leases also support recreational uses such as guided hunting and fishing, trails, campgrounds, and others.

Colorado voters adjusted that original constitutional language in 1996 because the word “maximum” became controversial. After all, the maximum profit from land would be made by selling it, which the Land Board could do and has done. Today it only owns 2.8 million acres. Also, more money might be made from subdividing and developing than from grazing or energy leases. But selling only generates short-term profits – pennywise but pound foolish. So, the 1996 language replaced “maximum” with a more appropriate standard: “to produce reasonable and consistent income over time.” Many other states have made similar adjustments to the original statutes.

State school trust lands still could not be used without generating revenue, such as if they were set aside for conservation uses like wilderness or national parks. But there might be a few exceptions, so Colorado voters authorized their Land Board to establish a “Stewardship Trust” to promote conservation and natural values, limited to 300,000 acres. The remaining trust lands still

earn over $280 million a year for the school fund, mostly from oil and gas leases, still fulfilling their original unique mission.

That original mission was called into sharp focus with the recent appointment of a State Land Board Director whose previous career has everything to do with land preservation and nothing to do with funding schools or managing leases. In fact, she was associated for decades with the most extreme ecoterrorists in the U.S., an association she says no longer represents her thinking, which has “evolved.”

Nicole Rosmarino faced tough questions because of her public cheering for Earth Liberation Front (ELF), which the FBI has called America’s “number one domestic terrorism threat.” ELF’s own press office said it uses “economic sabotage and guerrilla warfare to stop the exploitation and destruction of the environment.”

ELF was condemned by most environmental groups – even the Sierra Club once offered a reward for the capture of ELF arsonists. Rosmarino, however, cheered them on after they torched multiple buildings on Vail Mountain in 1998, in what the FBI called the “worst act of eco-terrorism ever in the United States.” Six perpetrators went to prison; one remains on the FBI’s most wanted list.

Rosmarino, though, told Mother Jones magazine she was delighted at “one of the most beautiful acts of economic sabotage ever in this state.” She also worked for Wild Earth Guardians and sat on the leadership council of the Rewilding Institute, which works to replace agriculture with native species. She has said she wants “massive herds of bison and pronghorn… prairie dog colonies, and lesser prairie-chickens conducting their ancient and provocative mating dances.”

She now says she is focused on “preservation,” not ecoterrorism, and I have no reason to doubt her sincerity. I am a big believer in second chances; I’ve needed several myself. But “preservation” is not the Land Board’s job, though purchasing “lands in the path of future development” has already been added to the Board’s website. There are plenty of agencies and programs involved in conservation work. But stopping development is no more part of the Land Board’s job than “rewilding” or dancing with prairie chickens.

Rosmarino has been praised for her skill at “raising large sums of money.” Great. But shifting the focus to preservation instead of revenue – beyond the 300,000 acres voters set aside for that purpose – would threaten at least some of the $280 million being raised for public schools. She is not the only state land board director in the U.S. who seems intent on changing the historic purpose of these lands; there are several others. They are in the wrong jobs to pursue that agenda, because the state land boards must raise revenue for the schools. That is what distinguishes state trust lands from all other public lands.