For the first time since the mid-1990s, there’s plausible reason to think the American economy could experience a sustained acceleration. Yes, it’s an AI story. As noted in “Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work,” last year’s exhaustive National Academies report,

Although it is notoriously difficult to predict the details of future impact, some estimates suggest as much as a doubling of the rate of growth in the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) from about 1.4 percent currently to 3 percent.

But Washington policymakers would be wise to hope for the best and expect … something less than the best. As such, they should embrace economic policies that might boost growth, regardless of the eventual impact of generative AI models.

Yet even there, caution is called for. In the new NBER working paper “Policies to Reduce Federal Budget Deficits by Increasing Economic Growth,” Douglas W. Elmendorf (Harvard Kennedy School), R. Glenn Hubbard (Columbia University Graduate School of Business), and Zachary Liscow (Yale Law School), argue that politicians peddling the seductive notion that America can simply grow its way out of its fiscal hole are selling 21st-century snake oil. Still, the right mix of pro-growth policies could at least make the inevitable reckoning with higher taxes or lower spending somewhat less painful.

According to the paper, the pro-growth policy arsenal is hardly empty, though it contains no silver bullets, according to this cautious analysis:

- High-skilled immigration offers the clearest evidence: Bringing in an extra 200,000 foreign workers with advanced STEM degrees might boost total factor productivity growth by 0.003 to 0.053 percentage points annually—hardly revolutionary, but not nothing.

- Research spending looks more promising, with tantalizing hints that government R&D investment might actually pay for itself by supercharging innovation.

- Housing reform could be the real jackpot: One cited study suggests that simply cutting through zoning red tape in seven major cities might have lifted GDP by nearly eight percent in 2010.

- Business tax cuts have a solid track record. The 2017 corporate rate reductions offset 26 percent of their revenue cost through faster growth.

- Electricity grid upgrades and permitting reform sound compelling in theory, though hard numbers remain scarce.

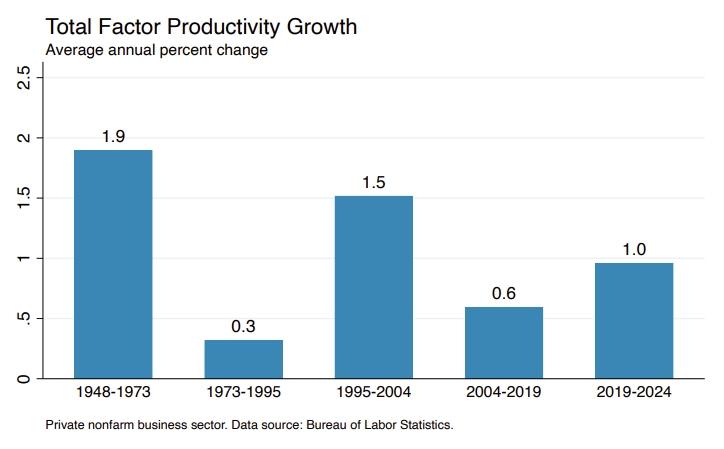

The sobering reality? Even if politicians could muster the political will to pursue this entire agenda—a heroic assumption—the combined effect would fall well short of the 0.5 percentage point annual productivity acceleration (total factor productivity, specifically, or the portion of economic growth that comes from improvements in technology, efficiency, and innovation) needed to grow Washington’s way out of its widening fiscal hole.

From the paper:

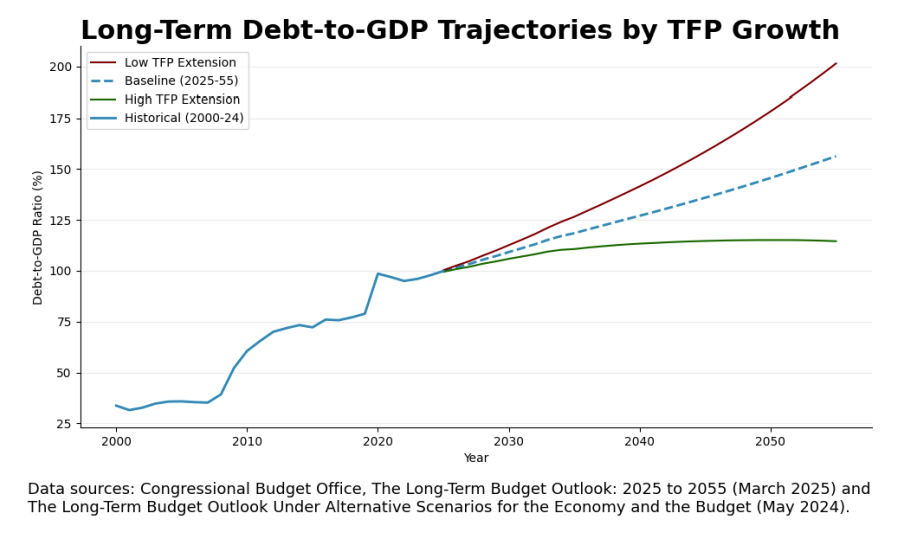

According to CBO’s projections, raising average annual productivity growth from 1.1 percent to 1.6 percent on a sustained basis would stabilize debt relative to GDP. We have found no evidence that such a large and sustained increase in productivity could be generated by plausible changes in government policy that would not themselves increase the deficit significantly. We conclude, therefore, that growth-enhancing policies almost certainly cannot stabilize federal debt on their own.

The post Thinking About Pro-growth Policy and Federal Budget Deficits appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.