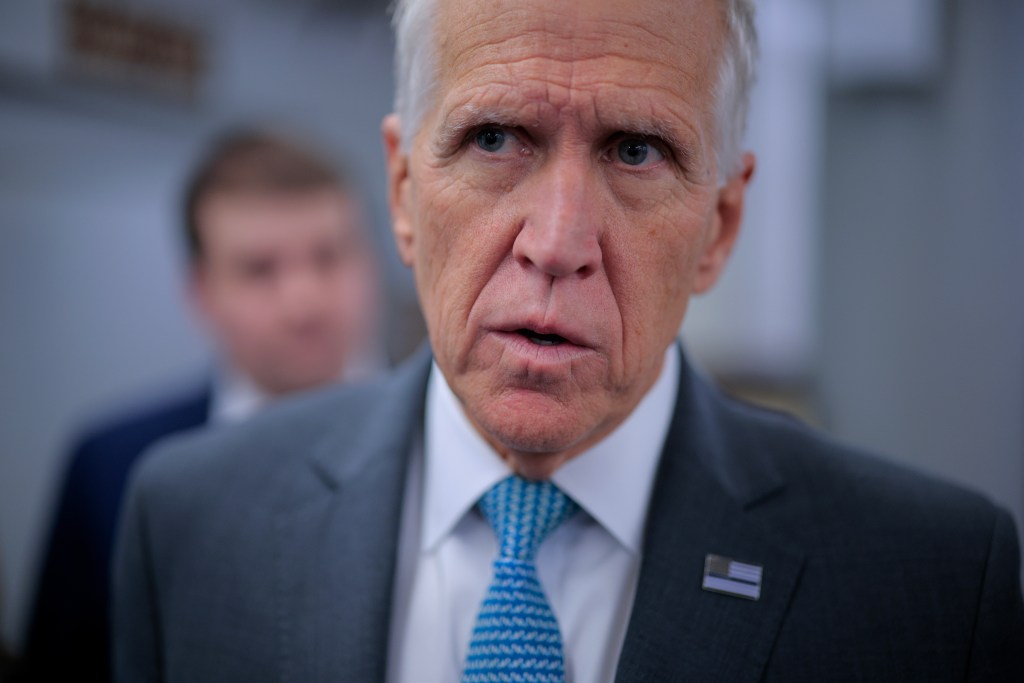

Sen. Thom Tillis was getting impatient. Despite repeated requests, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem had not yet appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee on which Tillis sits, so he announced he would place holds on DHS nominees until she testified.

Tillis characterized his stance as a response to Noem giving the committee the cold shoulder. Committee Chairman Sen. Chuck Grassley has asked Noem twice over the past year to appear before the panel, and only on Monday did the two reportedly agree to a hearing, which is set for the beginning of March. But until that day arrives, Tillis plans to keep his block in place.

“This is an appointment,” he told The Dispatch on Tuesday. “When game day comes, then we can talk about me lifting the holds.” But following the fatal shooting by Border Patrol agents of VA nurse Alex Pretti in Minneapolis on Saturday, he is also calling for Noem’s firing. “What she’s done in Minnesota should be disqualifying,” Tillis told reporters. “She should be out of a job. I mean, really, it’s just amateurish. It’s terrible. It’s making the president look bad on policies that he won on.”

Tillis would not say whether Noem should be impeached, and it appears he is not going so far as to demand her firing or resignation as a condition to drop the holds, but he has proven he is unafraid to use the Senate’s institutional mechanisms to try to get his way. Having announced in June that he would not seek reelection this year, Tillis is demonstrating just how much one senator can influence the executive branch’s ability to pursue its agenda.

A year ago, the two-term senator was in arguably the most difficult position of any incumbent in Congress. He had to ensure that he could overcome both a possible primary challenge from the right and a general election challenge from the left. As one of the few GOP senators who has pushed back against a handful of President Donald Trump’s actions he has disagreed with, Tillis bowed out following Trump’s announcement that he would entertain endorsing primary challengers to Tillis. This was after the senator voted against advancing the president’s priority legislative package, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. During that episode, Trump called Tillis “a talker and complainer, NOT A DOER” and later said it was “Great News!” that he would not seek reelection.

Announcing his retirement, Tillis said that he looked forward to “having the pure freedom to call the balls and strikes as I see fit.” Since he made his decision in the summer, he has made ample use of that freedom, becoming a thorn in the side of Trump’s agenda.

But he has not achieved that status simply by being a loudmouth or a critic. Both the party makeup of the Senate and the procedural traditions of Congress’ upper chamber give a lone senator enormous power, and Tillis’ position as a member of several key committees has allowed him to flex it.

“If senators really understand, given the vote margins, just how incredibly impactful they could be, they ought to start learning how to use them judiciously—to support the president and, in my case, support the Republican Party,” he told The Dispatch. The last part is key to Tillis’ own characterization of his efforts. He insists they are for the president’s benefit, though Trump might not see it that way given the obstruction Tillis has vowed to undertake.

Following the revelation that the Department of Justice is investigating Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, Tillis announced that he would oppose any nominee for the Federal Reserve “until this legal matter is fully resolved.” That opposition includes, Tillis said, the upcoming replacement for Powell, whose term ends in May.

His seat on the Senate Banking Committee gives him power well beyond what he would enjoy as being merely one out of 100 senators in a vote of the full chamber. The committee, which has jurisdiction over the Federal Reserve and handles nominees to its board of governors, is made up of 12 Republicans and 10 Democrats, so any GOP defection means a deadlock, and the vote fails. In the likely event that Democrats voted together, Tillis would be able to block any nominee.

Tillis and other senators worried that the investigation was a way of strong-arming Powell into pursuing economic policy favorable to the Trump administration. For many of them, the Federal Reserve’s independence to shape policy is paramount. “The reason why I felt like I needed to say something quickly: I was genuinely worried about how the markets would react if they thought it was the end of [the Fed’s] independence,” Tillis told reporters.

Procedural mechanisms exist for Senate Majority Leader John Thune to go around the committee and bring a nominee to the floor without its recommendation, but there are a number of deterrents to that. One is that such a move would likely ruffle the feathers of Republican senators who are not on the Banking Committee and incentivize them to vote against a nominee without a committee recommendation.

For Thune, circumventing the committee process would also contradict one of the pledges he made to Senate Republicans to win election as majority leader. In his first speech in his new position, he promised to restore the Senate as “as a place of discussion and deliberation,” and doing that meant “empowering committees, restoring regular order, and engaging in extended debate on the Senate floor.”

Thune has stuck to his promise to keep the committee process intact even as it was tested last year—by Tillis himself. The North Carolinian announced in May that he would oppose the confirmation of Ed Martin—whom Trump nominated as the U.S. attorney for Washington, D.C.—over the nominee’s previous defense of January 6 rioters. Like the Banking Committee, the Judiciary Committee also has 12 Republicans and 10 Democrats, so the opposition from Tillis meant the committee was deadlocked. Tillis’ opposition to Martin, Thune said at the time, “would suggest that he’s not probably going to get out of committee.” Trump withdrew Martin’s nomination.

Tillis would later flex his Judiciary Committee muscle to help preserve a 100-year-old tradition in the Senate amid Trump’s calls to scrap it. Grassley has shown immense resolve in resisting pressure from Trump to do away with what’s called the “blue slip” practice, which allows a single senator to effectively veto nominees to be attorneys and district judges in their state. The Judiciary chairman gives a blue piece of paper to both senators from a nominee’s home state, and if even one of them does not return it with an endorsement, the nomination stalls. While Trump has called on the Senate to end the practice, complaining that Democrats have used it to block some of his nominees, Grassley has so far refused, noting that nominees without their blue slips do not have the votes to get out of committee or get confirmed by the full Senate.

In a floor speech this past summer, Tillis recounted an exchange in which Grassley had come to him and said he was polling members on whether he had support to get rid of the blue slip. “Chair Grassley,” Tillis replied, “you can rescind the blue slip if you feel like you have the support, but you need to understand that I will honor the blue slip for as long as I’m a U.S. senator.” He meant that he would vote against any nominee before the committee who did not have both blue slips from their state’s senators. While other Republican senators have backed Grassley in keeping the blue slip, none have gone as far as Tillis has in vowing to oppose nominees who lack them.

“The president is rightfully frustrated—all presidents are—with the blue slip, but I think that it’s very, very important for the state senators to have a voice,” Tillis told The Dispatch in October after Trump made one of his many calls throughout the year to kill the tradition.

Tillis’ pledge to maintain the blue slip, at least until he is out of office at the end of this year, could have implications long into the future, as in 2016 when then-Sen. Dan Coats of Indiana withheld his blue slip for President Barack Obama’s pick for a circuit court judge, stalling the nomination. After Trump entered the White House, he successfully nominated Notre Dame Law professor Amy Coney Barrett for that position, and he eventually tapped her for the Supreme Court.

There is more to Tillis’ efforts than merely using procedure to block business, according to former Sen. Rob Portman, who represented Ohio in the chamber from 2011-2023 and served with Tillis for eight years. Even more important is the respect Tillis commands in a body that thrives on trust and personal relationships among its members.

“Thom’s ability to influence the result is less about what an individual senator can do procedurally and more about the fact that he is respected by both sides of the aisle,” Portman told The Dispatch. “And when he stands up against something, people know it’s based on the merits and that he’s not playing politics. That’s not true with everybody.”

As an example, Portman noted Tillis’ objections to the health care portion of the OBBBA. To assuage the concerns of moderate Republicans like Tillis, the bill’s architects added a $50 billion fund to cushion rural hospitals from the most dramatic effects of the changes to Medicaid.

“He got a number of senators to express concerns about the health care provisions,” Portman said. “In the end, he didn’t vote for [the bill], but he changed the outcome by attracting a lot of other senators to his point of view, and changes were made.”

Tillis has not always been an obstacle to Trump, however. Early in the president’s second term, Tillis cast a decisive vote to confirm Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, later indicating he had a modicum of regret, saying Hegseth was “out of his depth.”

Even on occasions when he has broken from Trump and taken actions to potentially block his agenda, Tillis has been reluctant to criticize the president himself. Like many Republicans, he usually blames the people advising Trump. In a June floor speech explaining his “no” vote on the OBBBA, he said Trump had been “misinformed” and that “those amateurs that are advising him” did not tell the president the full impact of the bill, which congressional Republicans have since labored to sell to voters.

Of the Powell investigation, Tillis said that the probe removed any doubt that “advisers within the Trump Administration are actively pushing to end the independence of the Federal Reserve.” Even as the senator was condemning Trump’s saber-rattling on Greenland and threatening to derail or stall more nominees in response, he took care not to direct his ire at the president. “To be clear, I’m not critical of the president,” he said at the very beginning of a CNBC interview last week. “I’m critical of the bad advice he’s getting on Greenland.”

In fact, he maintains he’s trying to help Trump.

“All I’m really trying to do, and I mean this genuinely, is to help be an adviser to the president, looking around corners,” he told The Dispatch. “He has some very smart people working for him that lack experience and implementation [ability]. And some of the times when I see our party or the president being criticized, it’s just because they didn’t think through potential risks, second-, third-order effect, unintended consequences, those sorts of things, which are ingrained in me because I did this in my professional career for 25 years.”

Though he has less than a year left in the Senate, Tillis has talked more about how he wants Trump to be remembered than about his own priorities in the twilight of his political career. Following the comments by White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller that it is the position of the U.S. government that Greenland should be part of America, Tillis unloaded on him—and insisted his doing so was to Trump’s benefit.

“I’m sick of stupid,” he said in a floor speech earlier this month. “I want good advice for this president because I want this president to have a good legacy. And this nonsense on what’s going on with Greenland is a distraction from the good work he’s doing, and the amateurs who said it was a good idea should lose their jobs.”