We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our readers about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

We’re actively working on improvements to better serve our community, and we want to hear directly from our members about their experience with our content. Will you take 5-10 minutes to share your thoughts in a quick survey? Your responses will help us continue to improve your Dispatch experience.

I’m often asked what people get wrong about trade, and—as our current moment depressingly shows—the list is long. One issue I always emphasize, however, is that trade is usually described as occurring between countries when in reality the vast majority of cross-border commerce involves private individuals (buyers, sellers, workers, investors) acting in their own interests, not according to some grand national strategy. Thus, for example, we routinely hear about trade between “the U.S. and Japan” or the “United States’ trade deficit with Mexico,” when those things are actually just shorthand for the aggregate decisions of millions of people acting independently of each other—and a misleading shorthand, at that. Government policy can, of course, affect these transactions—sometimes substantially—but they fundamentally remain the independent actions of private actors.

This reality is important for many policy and political reasons, but perhaps the biggest is that fans of government interference in cross-border transactions leverage the misconception to convince the general public, which doesn’t think deeply about these things, of their plans. It’s easier for most folks to support a tariff on, say, “Germany” than to support new U.S. taxes on Americans freely deciding to buy stuff from Germans—especially when they learn that “Germany” sells “the United States” more than “we” sell to “them.” It’s therefore incumbent upon those of us who oppose most tariffs—along with various other government restrictions—to explain what’s really going on, as well as the broader benefits of letting real people freely conduct real business without government getting in their way. (See this old Capitolism for more.)

Recently, however, we’ve seen the flipside of this policy lesson, as foreign individuals have increasingly abstained from buying American goods and services in response to U.S. government policies—mainly tariffs—and rhetoric. This reaction, which spans several countries and industries, is particularly interesting since retaliation is one area of trade that’s rightly focused on government action—because it’s typically governments doing the retaliating. Now, however, private individuals are pushing back against the United States—and, perhaps surprisingly, they might be imposing significant aggregate harms on the U.S. economy.

The Tourism Hit

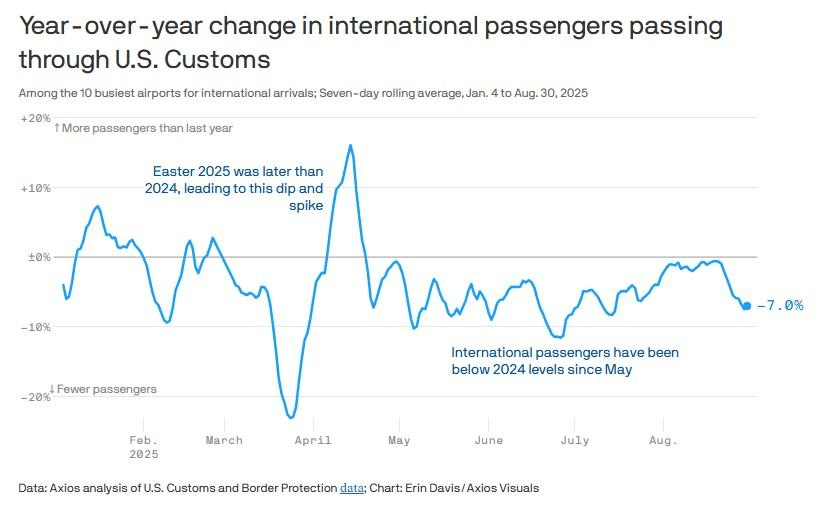

The clearest example of this trend is in the U.S. tourism industry, which has seen a noteworthy decline in foreign visits to the United States since the beginning of the year. According to Axios, for example, international arrivals at the 10 busiest U.S. airports have declined 7 percent this year versus last, and travel research firm Tourism Economics expects an 8.2 percent drop for the whole year—an annual total that’s well below pre-pandemic (2019) levels.

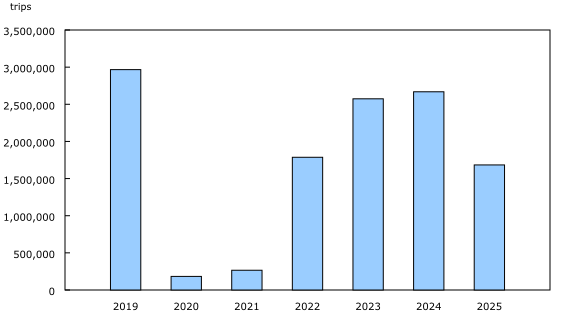

As Axios and many other outlets have noted, much of this decline has been driven by Canadian tourists upset about U.S. tariffs and President Donald Trump’s routine comments about making Canada our “51st state.” Tourism Economics adds that Canadian visits to the U.S. are down 25 percent this year, and specific destinations frequented by Canadian tourists—Las Vegas, Buffalo, Minnesota, New England, Florida, etc.—are seeing disproportionate hits to their local economies. The declines also aren’t limited to air travel: According to an August report by Statistics Canada, Canadian-resident car trips returning from the United States were down almost 37 percent in July versus the same month in 2024—amounting to almost 1 million fewer monthly visits and “the seventh consecutive month of year-over-year declines.” (Customs and Border Protection data show a similar drop.)

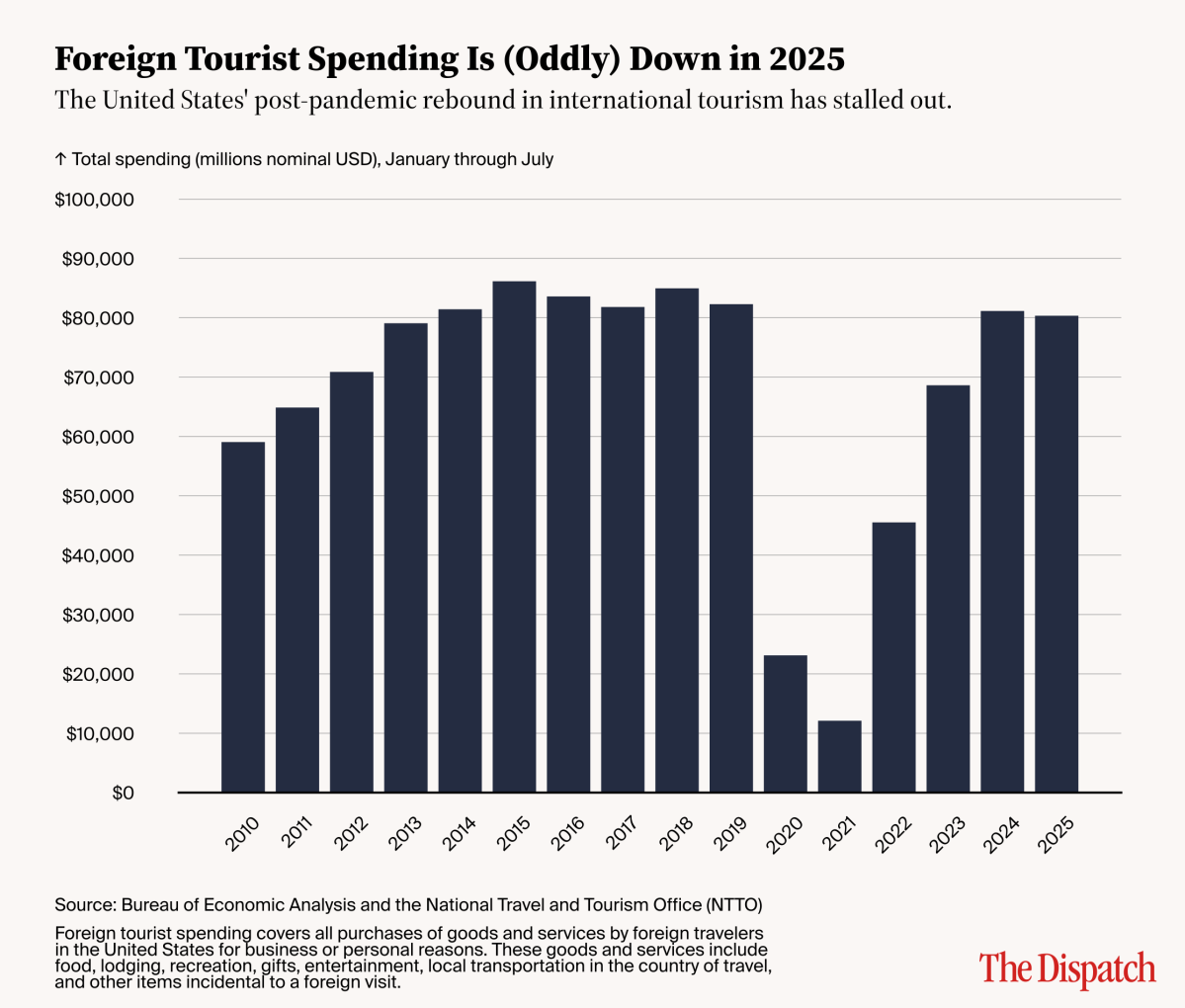

At this stage, it’s impossible to know the overall economic impact of these trends on the $3 trillion U.S. travel industry. For one thing, Axios notes, some U.S. tourism declines have been offset by gains elsewhere: Certain U.S. cities, for example, have seen more foreign tourists this year, mainly from places other than Canada. Nor do we know that the changes have been driven mainly by foreign tourists “retaliating” against the U.S. government’s trade, immigration, and other moves. Nevertheless, there are tons of anecdotes (and social media posts) about angry foreigners abstaining from U.S. travel, and it’s increasingly clear in the data that something happened in 2025 to stall or even reverse what had been steady, pre- and post-pandemic gains in international tourism and spending in the United States. According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, for example, total purchases of goods and services by foreign travelers in the United States—food, lodging, recreation, gifts, entertainment, etc.—peaked in December and have declined by about $800 million (or 1 percent) this year so far. They’re also almost $2 billion below the same period in 2019:

A broader measure of U.S. tourism exports, which includes education and medical travel, is also down from 2024 highs, save an April blip caused by an unusually-late Easter.

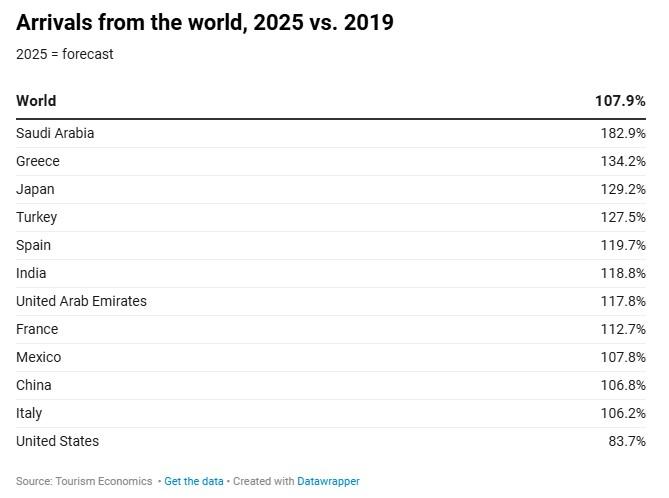

The 2025 dropoff in foreign tourism is even more stark when you consider four things: First and most obviously, the pre-Trump trend showed foreign visits and spending very much on the upswing. Second, the spending data aren’t adjusted for inflation—meaning the 2025 decline from previous years is larger in real-world terms (because spending in those years would be higher if reported in 2025 dollars). Third, the dollar has weakened substantially this year—something that should make international visits to the U.S. more attractive (the flip side of Americans feeling richer abroad when the dollar is strong). Fourth, global tourism is up overall this year, with significant gains in most major tourism markets putting the United States’ “small declines” into clear outlier status. The trend is forecast to continue through the end of the year—and beyond:

If these trends hold, it would mean billions of dollars in lost economic activity each year—pain that, the World Travel & Tourism Council warned in May, is largely voluntary and self-inflicted.

It’s Not Just Tourism

The private retaliation also isn’t limited to foreign tourism. Angry Canadians, for example, “are turning away from U.S.-made products,” motivating brands and retailers there to advertise their Canadian credentials—sometimes in, ahem, questionable ways:

Labels like “Designed in Canada,” “Prepared for Canada,” “Distilled in Canada” and “Proudly Serving Canadians” are proliferating, puzzling shoppers looking for country-of-origin information as part of the national backlash against tariff and annexation threats from the U.S.

Campbell’s got into hot water with the Buy Canadian movement with its line of Habitant soups, which includes a pea soup based on a traditional Quebecois recipe and features a small “Designed in Canada” label on the can. “Did they conceive of the recipe while visiting Banff?” one poster queried on a Reddit thread devoted to helping consumers discern Canadian content.

Canadian retailers also pulled U.S. brands from their shelves or offered non-U.S. alternatives for products like oranges, which typically come from Florida. And Canadian consumers have boycotted Amazon, Netflix, Disney, Starbucks, Burger King, Taco Bell, Subway, and other popular U.S. establishments and products.

Many Europeans are avoiding U.S. brands, too, and businesses there have also joined in. Business Insider reports, for example, that “Danish retail giant Salling Group introduced a black star label on electronic price tags to indicate products of European origin,” and “[a]pps that offer alternatives to US products have gained traction across the continent.” (One such app now has more than 30,000 downloads.) As BI reports, polls show significant numbers of Europeans are willing to boycott U.S. brands and many have already done so. And some distinctly “American” brands have indeed seen their overseas sales sag:

McDonald’s posted a 1% decline in global sales in the first quarter compared to the previous year, with CEO Chris Kempczinski citing an “uptick in general in anti-American sentiment,” especially in Northern Europe and Canada.

In Denmark, brewer Carlsberg said sales of Coca-Cola, which it bottles in the country, declined in the first quarter amid what CEO Jacob Aarup-Andersen described as a “level of consumer boycott around US brands.”

Other U.S. brands, such as Heinz and Lays, have also faced backlash. Europeans have soured on Tesla in particular: EU sales dropped to 77,000 over the first seven months of the year from 137,000 in 2024—a decline of almost 44 percent.

Dig around and you’ll find plenty more instances of private retaliation this year. Heightened nationalism and anti-American sentiment accelerated Chinese consumers’ shift from Apple’s iPhones to homegrown alternatives. Levi’s recently warned in a U.K. filing that “rising anti-Americanism as a consequence of the Trump tariffs and governmental policies” could cause British shoppers to avoid its clothing. And following Trump’s 50 percent tariffs this August, Indians have called for boycotts of popular U.S. brands like Pepsi, Subway, and KFC.

Of course, not all financial struggles of U.S. multinationals abroad—and U.S. exporters at home—should be attributed to people mad about Trump administration policies. Some of it stems from internal or market problems or, in the case of China and (to a lesser extent) Canada, government restrictions on U.S. goods and services. (Canadian provinces’ alcohol bans are proving particularly painful.) Yet governments in most of these markets haven’t retaliated, and it’s clear from loads of reporting that people abroad are protesting with their pocketbooks—whether because they’re mad about U.S. policy or because they simply need to hedge their business bets in a highly uncertain global trade environment. It’s also clear, moreover, that many other private responses are too small or hidden to be reported. A recent Washington Post piece, for example, included a random aside about a New York-based gear manufacturer facing a tough export market not because of foreign tariffs but simply because “international inquiries have dried up by about 50 percent … as buyers in other countries look for ways to bypass American manufacturers.” Whether those buyers are acting out of anger or strategy doesn’t really matter—what matters is that they’re acting, that they’re doing so in response to U.S. policy they don’t like, and that there are probably many more companies and people abroad doing the same.

Summing It All Up

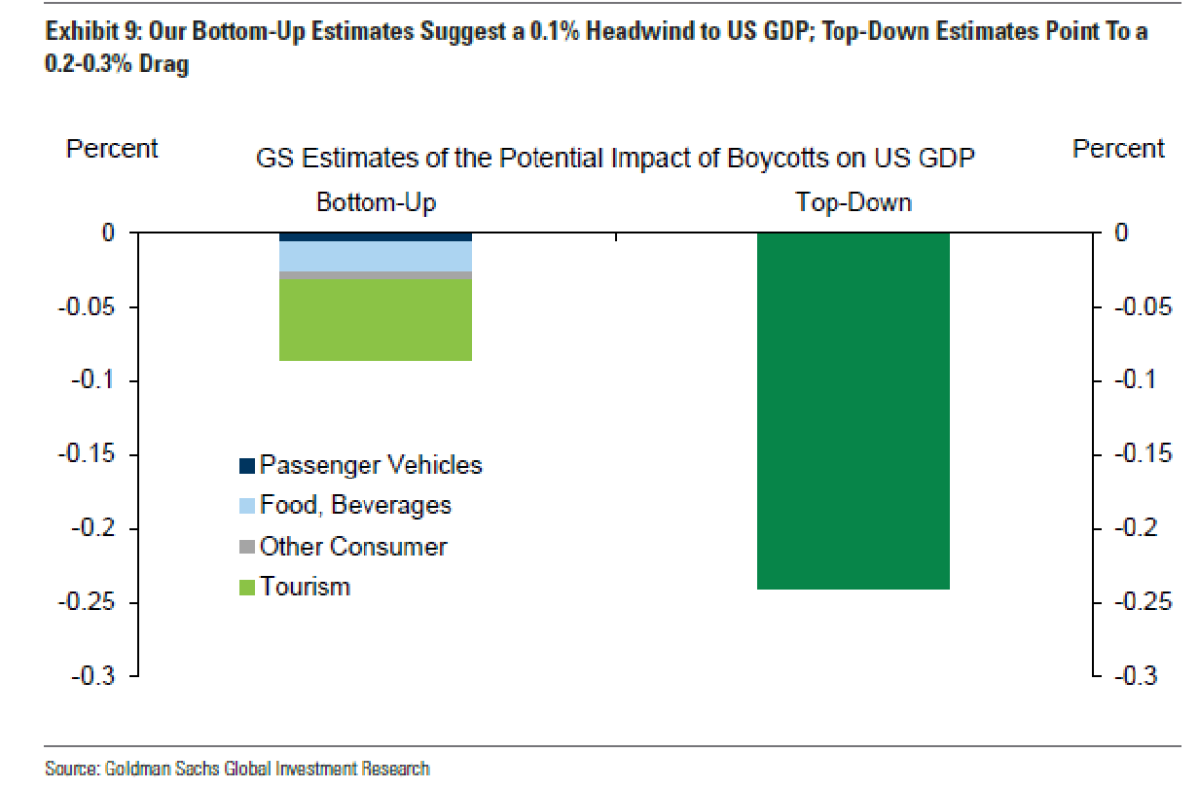

As we discussed a few weeks ago, one of the few economic surprises this year was the relatively few foreign governments responding to Trump’s tariffs with trade restrictions of their own. Millions of people in those countries, however, seem to have taken matters into their own hands, shunning American goods and services in response to U.S. tariffs and related Trump shenanigans. We don’t yet know the extent of these moves or how long they’ll last, but it’s increasingly clear that this retaliation is indeed occurring and could end up being sizable. Research on previous foreign consumer boycotts, for example, has also shown that their economic effects can be significant and long-lasting. This time around, Goldman Sachs’ back-of-napkin estimate found that foreign boycotts and related private retaliation could shave 0.1 percent to 0.3 percent off U.S. GDP in 2025, which would mean a loss of somewhere between $28 billion and $83 billion overall this year:

Those billions might not sound like much in a $30 trillion economy, but—leaving aside the fact that the trade wars have accelerated greatly since Goldman published its calculations in March—recall that Chinese retaliation to Trump’s first-term tariffs caused a mere $13 billion in annual damage to U.S. farm exports and necessitated a U.S. government bailout. Private retaliation against, say, the U.S. tourism industry probably won’t generate that kind of political response, but the harm is nevertheless substantial—and, unfortunately, a reminder that trade occurs between people … until some of them choose to stop.

Chart(s) of the Week