You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. Today’s newsletter has been unlocked for all readers. To read all our newsletters and stories, become a Dispatch member today.

Since Donald Trump’s very first day in the Oval Office, China has been the biggest justification for his protectionism—by far. During his first term, for example, America’s protectionists sold big U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports as a way to “de-risk” U.S. supply chains, partially “decouple” the two economies, tilt the bilateral relationship in the United States’ favor, and offset Chinese “dumping” and other unfair trade practices. Global steel and aluminum tariffs, meanwhile, were needed because Chinese overcapacity had flooded global markets, undermining domestic prices and industrial capacity. And when those tariffs (predictably) failed to achieve these stated objectives, the United States applied even more tariffs, with advocates claiming they were necessary to police Chinese content still entering the U.S. through other countries and to counter China’s industrial might and global influence.

As we’ll detail today, last week’s big U.S. trade deal with China raises new and uncomfortable questions about the efficacy of these “anti-China” tariff measures, if not their entire premise. And it should finally dispel the notion that the last decade of U.S. trade policy has, like, actually been some sort of 3D-chess strategy to contain China, instead of just the rote protectionism—and one president’s particular affinity therefor—that it so clearly appears to be.

The China Deal’s Terms

According to the White House readout of the deal (which these days is likely all the detail we’ll get), the two sides agreed to a temporary trade ceasefire across a range of issues. First, in exchange for new Chinese promises to restrict the exportation of fentanyl and its ingredients, the U.S. will cut “emergency” tariffs on Chinese imports from 20 percent to 10 percent and shelve Trump’s (never credible) threat of additional 100 percent tariffs, which were supposed to take effect on November 1. Both sides also will suspend for one year the broad and controversial export controls—China’s on rare- earth products and the United States’ on a range of commercial and “dual-use” items (including software and technology)—that led to this fall’s escalation. Washington and Beijing further agreed to a one-year suspension of fees on Chinese/U.S. ships entering U.S./Chinese ports, which were implemented earlier this year. Both sides also extended some other tariff exemptions, and Beijing agreed to cease other recent retaliatory actions that it had taken this year against U.S. agricultural products (especially soybeans), U.S. companies operating in China, and “legacy” Chinese semiconductor exports, which were halted because of an unrelated (mostly) issue in the Netherlands.

On the surface, this deal appears to be a simple—boring, even—replay of Trump’s first-term China deal, which calmed markets and reignited U.S. farm exports while still locking in higher restrictions on bilateral trade. Dig a little deeper, however, and both near- and long-term problems emerge—not least for anyone still using China to justify Trump’s endless trade wars.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

Bigger Implications—And None of Them Good

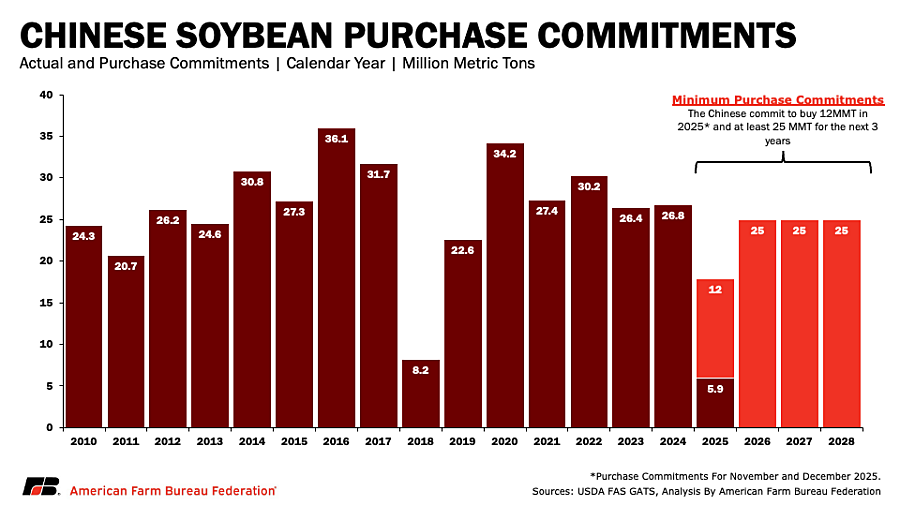

For starters, the deal at its best amounts to a temporary reprieve from the most intense bilateral hostilities while offering little long-term relief for U.S. companies, farmers, and workers caught in the middle of the ongoing trade wars. For example, China’s agreed purchases of American soybeans should help U.S. farmers over the next few years but, given that soybean exports to China were effectively at zero in 2025, that’s a really low bar. Assuming the soybean purchases actually happen (more on that in a sec), in fact, Chinese consumption would still be below the levels farmers enjoyed before bilateral hostilities ramped up in 2025 and far below where they were before Trump’s first-term tariff salvos:

Sales prices for American soybeans are also expected to be lower than in years past because, even with the Chinese purchases, U.S. capacity will significantly outstrip global demand—a situation owed in large part to the fact that, in the wake of U.S. tariffs, China has increasingly shifted to alternative agricultural suppliers (especially Brazil) while other U.S. trade deals don’t come close to filling the gap. Thus, the Wall Street Journal reports, the new U.S.-China deal doesn’t guarantee promised volumes unless American farmers are willing to take a price hit (emphasis mine):

While China this week booked its first shipments of soybeans for this marketing year, the agreement likely contains a potential loophole. Chinese negotiators again are expected to insist that China will only make such purchases based on “market prices,” according to people close to Beijing. This specific language is widely seen as a potential “out” for Beijing, allowing China to bypass U.S. supplies if they aren’t price-competitive. This is a critical distinction, according to Ken Morrison, a commodities trader focused on China, as U.S. soybeans face a very narrow window of competitiveness before Brazil’s harvest floods the global market.

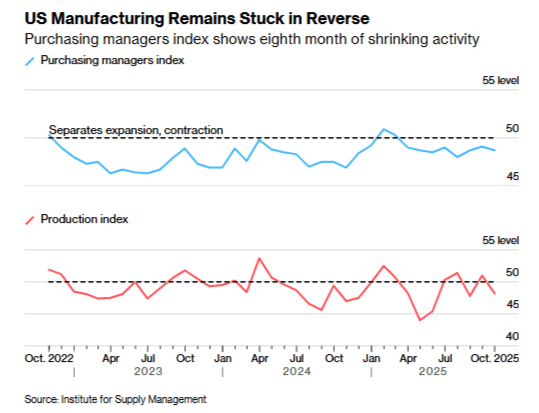

Other terms of the deal are an expressly temporary return to the summer 2025 status quo rather than a grand resolution of the many issues that have long plagued the bilateral relationship. A one-year suspension of rare-earth restrictions, for example, doesn’t mean much when—thanks to various regulatory restrictions and permitting bottlenecks—it takes years for mining and processing facilities to get up and running in the United States (if you can do it at all). Neither will China be making any systemic reforms to its export-dependent economy, nor to trade or human rights issues that have long aggravated Washington and other U.S. trading partners. So, the best we can say about this deal is that—as Trump himself has acknowledged—it’s a one-year punt that we’ll do all over again next year. That approach might provide sufficient relief for stock traders and certain U.S. importers with orders already placed, but it’ll do little to nothing to improve the uncertainty plaguing U.S. trade policy and, as the latest ISM manufacturing survey shows, the operations of many American manufacturers today.

Other problems with the deal are more fundamental. Most obviously, it suffers from the same lack of enforceability as the “Phase One” deal Trump made with China in 2019. That deal, you may recall, also included headline-grabbing Chinese commitments to purchase massive amounts of American stuff (especially agriculture), but—as I predicted on these pages in 2020—its lopsided design and vague terms all but ensured Chinese noncompliance over the longer term. According to a recent note from the American Farm Bureau, for example, China’s Phase One agriculture purchases started out strong but slowed dramatically in the following years:

Despite provisions allowing for consultation should the purchase commitments fall short, China gradually redirected portions of its feed, cotton and livestock imports toward alternative suppliers, and U.S. exports to China began to slow, dropping to $32 billion in 2023 and $27 billion in 2024. Year-to-date, through July 2025, U.S. exports to China stand at only $14 billion.

AEI’s Derek Scissors grumpily adds that Chinese noncompliance wasn’t limited to farm exports or even the Phase One deal, and we should expect similar things this time around:

The phase 1 trade agreement in 2020 failed quickly. Trump is rarely explicit about China joining the World Trade Organization, but in trade actions he ignores the Sino-American accession agreement, seeing as China has done so for many years already. And it’s not just the US. Beijing repeatedly violated a trade agreement with Australia over political criticism, for instance.

There was also the PRC’s promise to supply magnets using rare earth materials, which didn’t last four months. Yet here we go again. Xi will promise on rare earths, on fentanyl, on Russian oil. The Trump administration will tout how important it all is and threaten serious consequences if Beijing reneges. Then China will bend its commitments beyond recognition and the US will do nothing. Just like earlier this year. Just like in 2020.

The new deal also cripples the popular idea that China—not Trump’s deep and abiding public love of tariffs—is driving the president’s protectionist policies. You may have heard, for example, that U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports are still hawkishly high at roughly 45 percent: “emergency” tariffs for fentanyl (now 10 percent) and the trade deficit (also 10 percent), plus 25 percent tariffs imposed during Trump’s first term under a different law (Section 301, intended to fight “unfair trade” practices). Three big asterisks, however, undermine this claim and show U.S. policy to be preferencing China in many important areas.

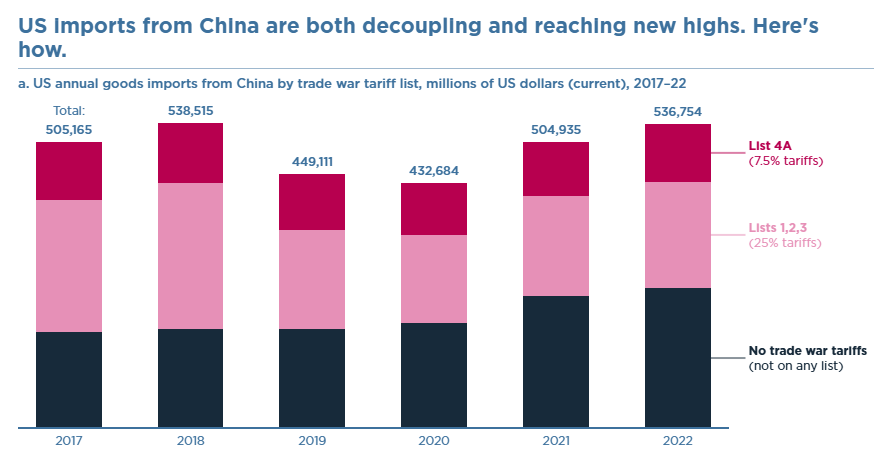

First, the highest Section 301 tariffs cover only some Chinese imports, leaving more than half subject to lower (7.5 percent) tariffs or none at all. As the Peterson Institute’s Chad Bown noted in 2023, these lower-tariff goods (shown in black and dark red in the chart below) have become an increasingly large share of Chinese imports in recent years:

Second, the 10 percent “reciprocal” tariffs exempt several categories of goods—most notably consumer electronics (smartphones, laptops, gaming consoles, etc.)—that China produces and exports in large quantities and that are also exempt from the Section 301 duties. For these products, the total “Trump” tariff is just the 10 percent fentanyl levy—unlikely to seriously discourage these goods from entering the U.S. market.

Third, and most importantly, the fentanyl tariff reprieve comes as Trump has imposed high U.S. “reciprocal” tariffs on all other countries—especially China surrogates like Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh, India, and Brazil, as well as close allies like the U.K., Australia, Europe, and Canada. This dynamic is very different from Trump’s first term, when only China faced broad, country-specific tariffs, and—the New York Times explains—it directly undermines the administration’s own trade policy goals for China:

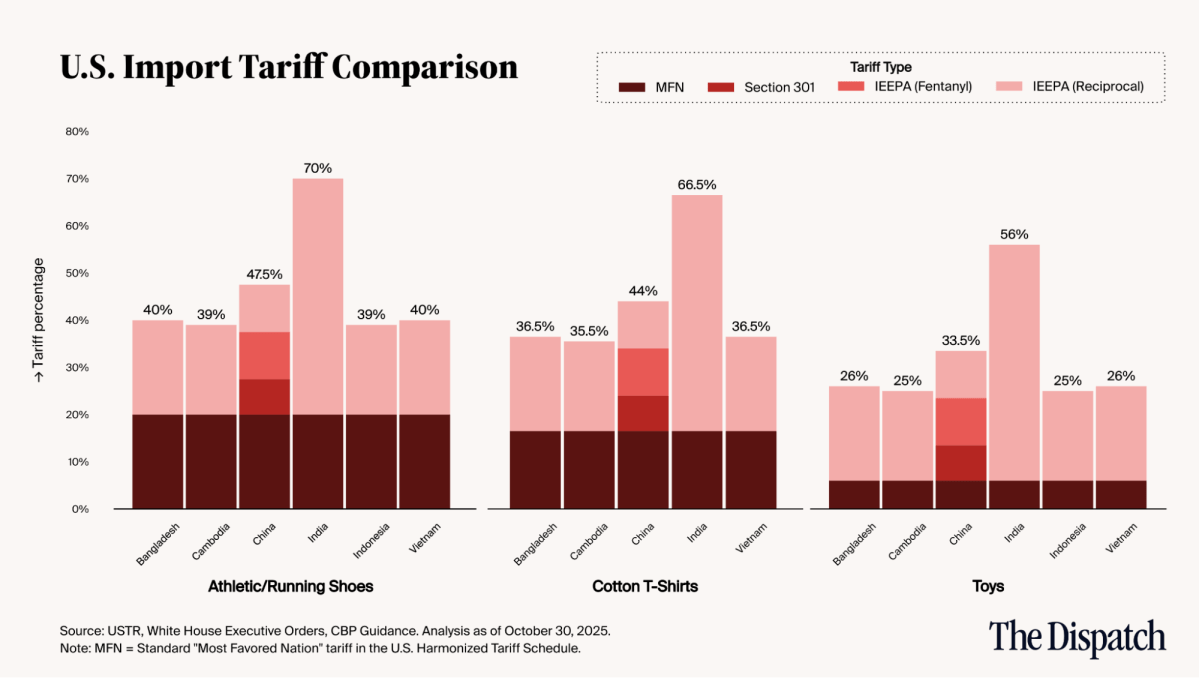

Although U.S. tariffs on Chinese products are high, American tariffs on certain products from other countries are now sometimes similar or higher, for reasons that make little sense. For example, Mr. Trump has imposed a 10 percent “reciprocal” tariff on exports from Britain and Australia, now the same reciprocal rate as for China. The administration says that tariff is directed at offsetting the U.S. trade deficit, but the United States runs trade surpluses with both Britain and Australia, while it racked up a nearly $300 billion trade deficit in goods with China last year. …

Countries in Southeast Asia, where many companies have moved their factories after leaving China, typically now face a reciprocal tariff of 19 or 20 percent, the same as or slightly lower than the base line tariff on China. But economists said countries like Vietnam and Cambodia could be heavily affected by the administration’s plans to put an additional tax on goods that are made with a certain proportion of Chinese content.

Given these other tariffs, the Times adds, the China deal actually “removes some of the urgency for companies to find factories outside China” and “chips away at the economic advantage that companies had expected from moving factories to Brazil, Vietnam and India” (among others). Indeed, you can see this tariff irrationality clearly in things like toys, apparel, and footwear, where China has large systemic advantages over its smaller Asian rivals and now faces tariffs only slightly higher—or in India’s case much lower—than those facing the countries that were supposed to benefit from Trump’s alleged China hawkishness:

Adding insult to this injury is the fact that, prior to the China deal being announced, several of the Southeast Asian nations agreed to gunpoint deals with Trump that locked in their 19 to 20 percent “reciprocal” tariff rates. Thereafter, Trump not only dropped China’s fentanyl tariff by 10 percentage points but then suggested it could be eliminated entirely if Beijing follows through on its fentanyl commitments. Something tells me these governments aren’t super-excited about their trade deals now.

Surely, there are other tariffs the U.S. could impose to offset some of these new Chinese advantages. For now, however, the combination of lower China tariffs and higher everyone else tariffs has shifted U.S. trade policy away from China hawkishness and toward global isolationism writ large—even if it benefits Beijing in the process. Other terms of the new bilateral deal, such as the United States’ unprecedented reversal of security-related export controls, also benefit China in surprising ways and indicate that Beijing may have more leverage today than the Trump administration is willing to admit.

This highlights the final problem that the China deal reveals: Recent U.S. isolationism has helped tilt the global balance of power toward China and away from the United States. As we’ve discussed repeatedly, the United States is a huge market but still a relatively small share of global trade, thus limiting Washington’s ability to force exporters into eating U.S. tariffs or to coerce the Chinese government into doing its bidding on trade or anything else. One obvious way to counter the latter issue was for the United States to create a voluntary coalition of like-minded countries freely trading with each other—building not only diplomatic goodwill but also a collective industrial base that outmatches even China’s behemoth and decreases dependence on the Chinese economy and exports.

This was a big goal of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Trump of course abandoned in 2017, and it’s a continuing problem that the U.S. hasn’t inked a new free trade agreement in more than a decade. Yet what Trump has done is actually worse than simply refusing to deepen trade ties and worse than doing nothing at all. Instead, Trump’s high and erratic tariffs on alternatives to China undermine American manufacturers and put Chinese imports closer to parity in the U.S. market (see above). And, as The Economist just smartly detailed (and as new data show), the tariffs also have caused governments to defend against new U.S. coercion by trading less with the United States and more with each other—undermining U.S. strength and influence along the way:

[O]penness can also protect. Albert Hirschman, a liberal economist who fled from Nazi Germany, saw that rules could shield as well as constrain. Having watched the Third Reich use trade to subdue its neighbours in eastern Europe, he warned that the power to interrupt trade relations becomes a powerful instrument of political pressure. His answer was not to turn inward but to spread risk. True independence, he argued, came from diversification—broad commerce with many partners, so that no single one could choke off a vital flow. In a world where a hegemon is willing to coerce, integration is what preserves sovereignty. …

Brazil shows how this plays out. When Mr Trump announced his 50% tariff, officials reached instinctively for the rulebook. The South American giant is one of the World Trade Organisation’s most litigious members—filing the fourth-most complaints, after America, the EU and Canada. But with the WTO enfeebled, Brazil is looking to deepen ties with others. Celso Amorim, Lula’s chief adviser, calls it “a vaccine against arbitrary moves from any one power”. In a world ruled by bullies, the best defence against infection by one country is exposure to many. …

Around the world, governments are reaching the same conclusion. Middle powers like India, Indonesia and Mexico are pursuing autonomy through openness. Mr Trump’s tariffs are pushing others to tie themselves more securely to trade rules. Economic integration was once considered a threat to sovereignty. Today it has become its shield.

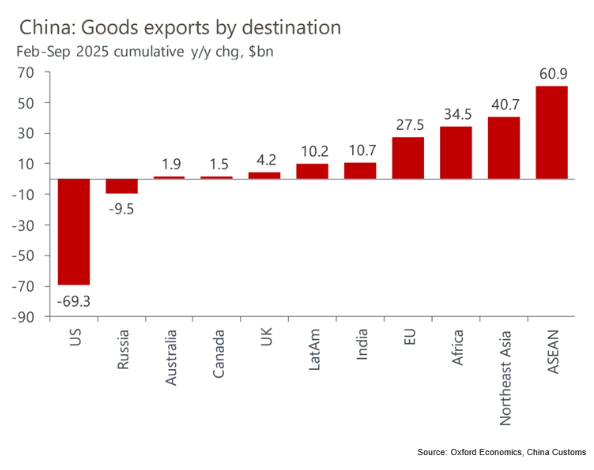

A major beneficiary of this approach has been China, which has pursued the mirror image of Trump’s isolationism—deepening trade engagement with non-U.S. countries, diversifying exports and imports away from the United States (though certainly not entirely), and in the process muting the United States’ ability to use high tariffs as leverage in bilateral talks.

Without freer access to non-China imports and new alternative markets for U.S. exports, on the other hand, Washington can be more influenced by Chinese protectionism and retaliation—as the soybean and rare-earth messes just showed. It’s thus little surprise that many observers believe that the China deal shows a new parity in the bilateral relationship—something Trump himself seemed to acknowledge when calling it the “G2” (a term Chinese nationalists “triumphally” welcomed).

That parity is in no small part owed to a decade of protectionist U.S. trade policy.

Summing It All Up

Readers of Capitolism surely know by now that China’s own economic and other headwinds make me less fearful of its long-term ascendance than many hawks in Washington would have us believe. In the nearer term, however, Chinese policy and its government raise real concerns and challenges for the United States and its allies—issues that demand U.S. policy reforms that leverage our systemic advantages, such as those that I (and many others) have offered. With few exceptions, however, these ideas have been ignored in Washington for a decade, while tariffs have been embraced. In last week’s China deal we can see the results of these efforts, and little of it is good.

Chart(s) of the Week